It’s 2060 and the Aids crisis is finally over, with the HIV virus finally wiped out from the face of the Earth. And it gets better (or worse, depending on how you look at it). The bug had mutated into a gene that can be manipulated into a psychoactive drug once extracted from the human body. So an extensive underground network of fluid slaves has been established. In other words, a prolific sperm factory.

These poor males have to wank non-stop and so that their much-coveted man juice can be harvested and sold off to the joy of recreational drugs users. A little bit like the basement slaves in John Waters’ classic Pink Flamingos (1972), except that there are no babies involved.

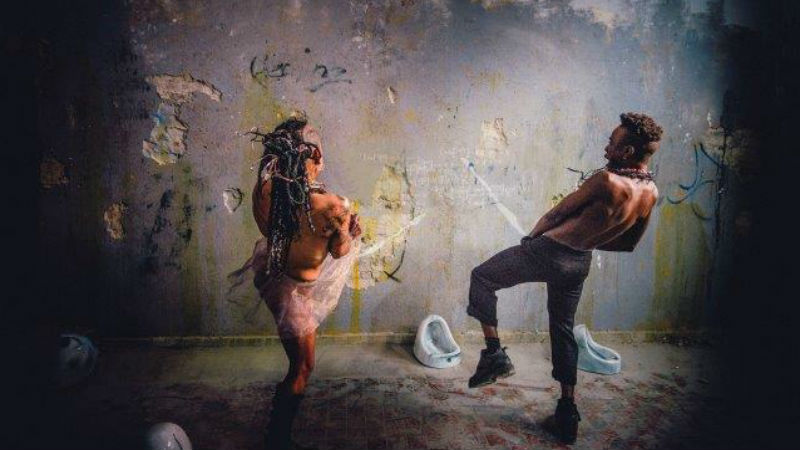

Women are also involved: there’s also plenty of urine, sweat and other bodily secretions. Yet the film never feels repulsive. This is nothing like Isabelle Adjani on the subway in Possession (Andrzej Zulawski, 1981). Fluid0 is vibrant with colours, futuristic CGI effects and flashing lights. It’s entirely pleasant and fun to watch. It’s also very sexy. And it’s not just the lights that flash! To boot, digital has a double connotation: there’s a lot you can do with your computer but also with your finger!

The slaves seem to have a lot of fun at what they are doing. Maybe they are also experiencing the effects of the psychoactive drug, for which they provide the vital staple. The factory is populated with all sorts of characters: trans and cis, old and young, male and female, gay and straight, black, white and all of colours of the race spectrum.

There is also a “sexecologist, plus a a “porn terrorist”, although I’m not entirely sure what they do! People are having fun, and penetration is never mandatory. “Enjoy your soft on, no need for an erection”, a female character succinctly challenges the established orthodoxy of our phallocracentric world. Challenging the norm seems is the leitmotif, it seems.

Ultimately, Fluid0 is a dirtylicious, transgressive and futuristic post-porn art piece. The charming indie soundtrack by Aerea Negrot gives it a nice and amusing final touch. It’s not a perfect movie though. The plot becomes subordinate to the imagery way too often, and so the narrative gets a little manneristic. The idea of HIV being converted into a drug in a very interesting one, and I wish this had been explored in more depth. Still, a wet and salacious evening is guaranteed.

Fluid0 is the closing film at the Fringe Queer Film Fest, on November 19th.