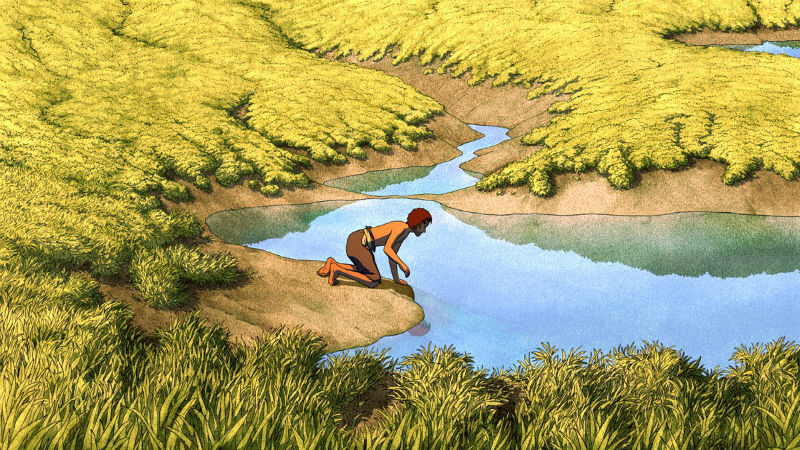

Around the age of 16, people in the spirit world must visit the world of the humans, with whom they are warned not to interact, as a rite of passage. Thus it is that teenage spirit girl Chun must pass through the elemental maelstrom linking her world and ours whereupon she is transformed into a red dolphin and made to spend seven days in the seas of the human world. On her sixth day, she hears a teenage boy play a dolphin-shaped flute to his sister; on her seventh she sees blue dolphins struggling in a fishing net. Her return to her world is blocked when she becomes entangled in a net between her and the whirlpool until the boy rescues her only to be himself fatally sucked into that whirlpool. This is more or less how the Chinese animation Big Fish & Begonia sets off.

Safely back in the spirit world, Chun understandably feels she owes him a debt so trades half her life to a soul keeper in exchange for that of the boy: she must nurture the boy’s soul which will be given the form of a fish in her world and release him back into the human world when the fish reaches adulthood, at which point she will die but he will live. She names the fish/boy Kun after a legendary sea creature of immense size.

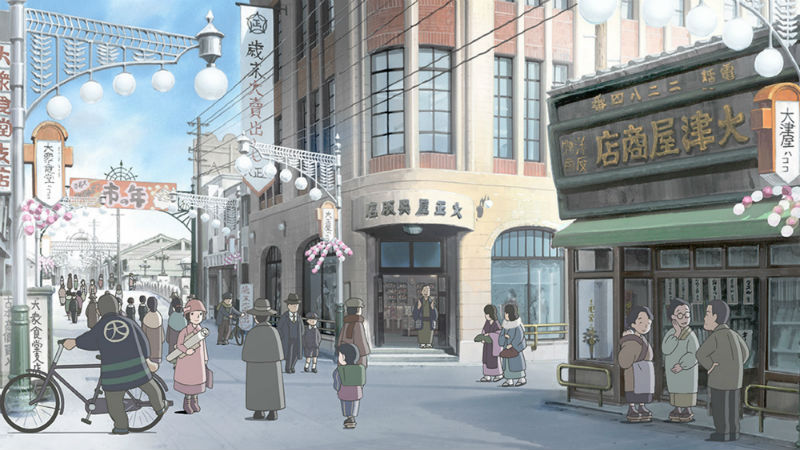

There’s a lot more to it than that: firstly, an unrequited love story introduces teenage spirit boy Qiu who fancies Chun and looks out for her even though she treats him like no more than her big brother. Then, while the old aged male soul keeper watches over the souls of departed good people incarnated as fish, his equally old female counterpart watches over the souls of departed bad people incarnated as mice. Chun’s late grandma is reborn as a phoenix; her beloved grandpa, a Begonia tree. Also in the mix are a deadly two-headed snake, a mystical stone dragon and an unearthly ferryman who steers his barge along the clouds. And while in the human world the red dolphins swim among the seas, in the spirit world they soar through the skies along with cranes and dragons.

The whole is rendered in beautifully drawn animation as effective at portraying in the heroine’s internal life as it is in bringing incredible landscapes and fantastic creatures to the screen. The pace is mesmerisingly slow in places, breathtakingly action-packed in others. Where else can you see a girl sell half her life to save someone else’s, a man play mah-jong against three other versions of himself or the terrible portent of snow falling in the middle of Summer? For the finale, it throws in cataclysmic floods and waterspouts descending from the skies.

The production, which was intermittently on then off for some 13 years, was ultimately promoted by posts on Weibo (China’s answer to Twitter) then financed by China-based crowdfunding. Very much an indie production by two directors with a unique vision, it’s a landmark entry in the annals of fantasy film and animated storytelling which deserves to be widely seen. Its limited UK and Irish release means you’ll need to make a special effort to see it. You should do so though because this magnificent home-grown Chinese offering demonstrates just how tired and formulaic most Hollywood fantasy and/or animated films are. Don’t miss.

Oh, and be warned there’s a key scene buried in the middle of the end credits.

Big Fish & Begonia is out in the UK on Wednesday, April 18th. It is screening in both subtitled (independent cinemas) and dubbed (Showcase Cinemas) versions. We recommend the subtitled version as screened to press. Click here to see where it is being screened. Watch the film trailer below:

Subtitled:

Dubbed: