Best known to international audiences for his extravagant visual style and the existentialist – at times even pessimistic – undertones that permeate the totality of his filmography, Paolo Sorrentino is considered by several prominent film critics and scholars to be the natural successor of legendary Italian cinematic figures such as Michelangelo Antonioni, Bernardo Bertolucci, and Federico Fellini. Keeping in toe with the post-WW2 wave of Italian, and European in general, art cinema, though keeping a safe distance from the Neorealism tradition, Sorrentino‘s oeuvre claims its own place in the country’s rich filmmaking history while retaining those essential traits, both thematic and stylistic, needed to distinguish his films from those created by his worthy predecessors.

Sorrentino‘s trademarks comprise a buzzing energy as far as film aesthetics are concerned, swooping camera movements that frequently focus on facial close-ups of the protagonists, main characters – almost exclusively male and middle-aged – who often wander around the big cities in a nomadic search for the lost meaning or anything that could ascribe value to people and their surroundings, and a commentary and critique of the current national status quo in respect to society, culture, and arts. In his 2014 Oscar acceptance speech for his magnum opus The Great Beauty, which won the Best Foreign Language Award, Sorrentino named the four major influences that shaped his work from the beginning of his career until the present day: Federico Fellini, Talking Heads, Martin Scorsese and Diego Armando Maradona. This reveals that he draws from cinema and culture from both sides of the Atlantic. His work seamlessly blends the commercial with the intellectual form of moviemaking. But it was Fellini’s work that had the most profound mark on Sorrentino‘s work.

Below are some interesting snippets of the life and career of a complex and multilayered artist.

…

.

One lonely boy

Born in 1970 in the southern city of Naples, the Italian auteur suffered an ineffable tragedy during his teenage years as he lost both parents in a freak accident of carbon monoxide leaking while on a holiday getaway on the mountains. Sorrentino was fortunate enough not to follow his father and mother in their fatal excursion, as he preferred to stay home and watch his favourite team, Napoli, and the great Diego Armado Maradona live at Napoli’s home stadium, San Paolo. His battle with the overwhelming grief over his parents’ demise is graphically illustrated in his latest film, The Hand of God (2021; pictured below), a largely autobiographical feature in which the protagonist, Fabietto functions as the director’s alter-ego, a boy struggling with the post-puberty complexities and dilemmas while at the same time aspiring to become someone in the Italian filmmaking scene. At the age of 18, Sorrentino first came into contact with cinema by watching both American and Italian movies and developing a sense of cinematic taste through the independent American cinema movies as well as Martin Scorsese’s early masterpieces.

.

Two’s company

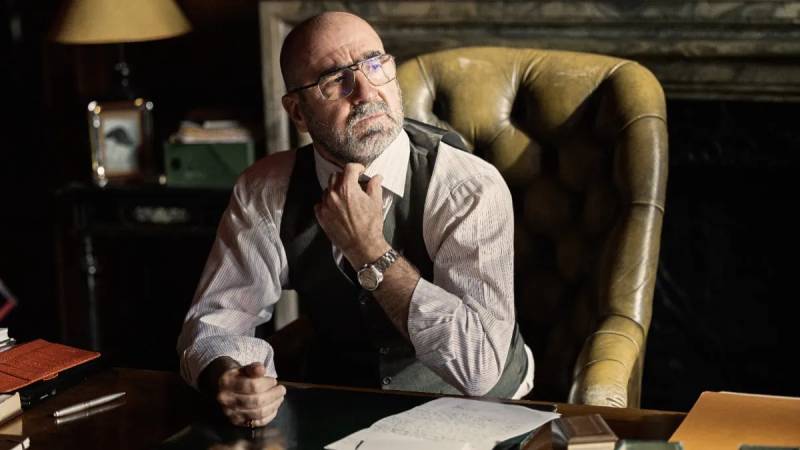

Even from the first stages of his illustrious career, Sorrentino linked his name as director with that of Toni Servillo, one of Italy’s most skilled and versatile actors, with the two artists forging a brotherhood that still lives on. In a discussion between the two, Sorrentino explicitly stated: What I’m looking for in an actor – especially a lead actor – is realism. Realism in a performance can be exceptional, but it must not be conventional or grey. You’re able to create something realistic and unique at the same time – to bring to the surface qualities that are essential to cinema, while also making events familiar and relatable to audiences” while Servillo added: “An actor essentially has to testify for the director, with his or her own body, inside the parameters of the film. That’s absolutely necessary to preserve trust between director and actor” (you can read the full conversation here). The unique chemistry between them was born and made possible the filming of some of the most distinct in their quality titles that modern European cinema has ever created.

Sorrentino’s debut feature, One Man Up (2001) also signalled his first collaboration with Servillo (pictured above in the film poster), who played a lead role for the first time in his career. Nevertheless, it was not until a few years later that the formidable director-and-actor dyad made their breakthrough with the 2004 sophisticated crime drama The Consequences of Love, a movie featuring a lonely protagonist, Titta Di Girolamo, who is forced to work for the Mafia as an intermediate laundering money on their behalf. Titta’s life will be turned upside down when he meets a stunning young woman (Olivia Magnani) who works in the hotel in which he resides and instantly falls in love with her. This film established Sorrentino’s reputation on an international scale, while it also earned several distinctions (most notably it became an entry in Cannes’ Official Competition). The movie’s existential dimension is brought forth by Sorrentino’s masterful direction and unorthodox shots that deftly capture the protagonist’s inner state of solitude and despair. Servillo is, once more, excellent as the taciturn Titta Di Girolamo while Magnani’s ravishing looks literally shine onscreen, forcing the members of the audience to identify with Titta’s motivations and his quest for redemption and liberation from the shackles tying him to the underground.

.

A real diva

What followed was Il Divo (2008; pictured below) the biopic of controversial Giulio Andreotti, the second longest-serving post-War Italian prime minister (after the late Silvio Berlusconi). Sorrentino is a brilliant as well as unconventional auteur and in this movie, he opted for a rather non-traditional narrative approach that attempts to cover a wide time-span during which Andreotti played a dominant role in the Italian public life. Thus, the story doesn’t progress linearly but adopts a rather fragmented character as we see the protagonist in a variety of social encounters, private as well as public. In that way, Sorrentino effectively avoids imposing his assessment on Andreotti’s persona to the audience and shrewdly evades the convenience of providing definite answers and introducing prejudiced conclusions regarding the film’s subject. Furthermore, we watch Toni Servillo delivering another brazen performance, perhaps the best of his career so far, portraying Andreotti as a laconic, almost cryptic personality who hides under a vast number of layers which are meant to obscure or even conceal his true character as a human being. It should be noted that Andreotti was a man who had a thousand nicknames, such as “The Sphinx”, “Hunchback”, “The Fox”, and the titular “Divo”. Servillo uses kinesics and body language in a way that should be set as an example for all aspiring actors around the world and succeeds in adopting Andreotti’s body posture and above all his inscrutable, almost deadpan, facial expressions.

Even though Il Divo is essentially a political biopic, it is also a film in which Sorrentino reveals his influences by American auteurs such as Martin Scorsese and Francis Ford Copolla. In the beginning of the movie, we are witnessing a string of murders taking place onscreen abetted by an explosive pop music score and captions rolling out of blinds. The aesthetics are reminiscent of Copolla’s classic Godfather trilogy while Andreotti as a protagonist seems to carry within him an existential gloominess and an anti-hero quality akin to that of Travis Bickle in M. Scorsese’s Taxi Driver.

The operatic style of the production is enhanced by the soundtrack composed by Teho Teardo in 2008 reaching its climax in the final scene that is set before Andreotti’s Palermo trial.

.

The beautiful and the vulgar

As we’ve already mentioned in the introduction of this article, Sorrentino is frequently compared to and associated with Federico Fellini, as both the grand Italian creators share several affinities, without however their two bodies of work becoming identical in any sense. The similarities are clearly discernible in Sorrentino‘s magnum opus, The Great Beauty (2013), a film heavily reminiscent of Fellini’s La Dolce Vita (1961), where we follow the ostensibly futile roving of the protagonist, author and journalist Jep Gambardella, played in perfection by Toni Servillo, around the streets of Rome, witnessing the all-encompassing decadence of the Italian upper-class that manifests itself in the vulgarity of the exorbitant parties and other debaucheries, that put a dark veil over the Eternal City’s beauty.

Both Sorrentino and Fellini’s films are set in Rome, featuring journalists as protagonists and criticising the social milieu of each time period, with the spotlight put on the disillusionment of a generation which has long abandoned the ideals of the past in favor of pointless celebrations that become more and more barbaric over the course of time. Plus, Toni Servillo is for Paolo Sorrentino what Marcello Mastroianni was for Federico Fellini, both delivering unforgettable performances in their respective roles with the former winning the 2014 David di Donatello Award for Best Actor. The news of his childhood amore’s premature death will ignite Gep’s innermost journey to reassess his life, contemplating his past, the missed chances, the mistakes, while the desire to write will inevitably resurface. The photography is magnificent, with many imposing shots of Italy’s charming capital. This elegance is pitted against the decadence and vulgarity of the city’s aristocracy, which is caustically satirised by the director, who also pens the film. The humorous aspect is also present in The Great Beauty, though it is counteracted, and sometimes even obliterated, by Gep’s somber remarks and observations on a number of themes reflecting the modern human condition, such as artistic inspiration, death, modern art, and, of course, the meaning of love. The title of the film finds its justification at the end of the film, when the protagonist is asked why he hasn’t written a second novel for more than four decades, Gep admits: “All of my life I’ve been searching for the great beauty, but I never found it”.

.

The hand of the filmmaker

Sorrentino‘s latest feat to date, the 2021 autobiographical flick The Hand of God, the title being a direct reference to one of the most contentious moments in Diego Armando Maradona’s glorious career, is the movie in which the Italian auteur returns to his childhood, that is forever marked by the overwhelming grief over the demise of his dear father and mother at the tender age of 16, and faces again, in a more mature stage of his life, the challenges that scarred his soul and molded his personal as well as his artistic identity. The predominant theme in The Hand of God is none other than death itself. When a journalist asked Sorrentino if all of his films are ultimately about death, he answered: “Yes, I couldn’t make a film without touching on such an important issue. For human conditions, there are five issues that are key, and death is one of them.” What are the others? “Family, eroticism, happiness, and loneliness”.

The character’s obsession with the notorious phenomenon of the captain of the Argentinean national team and captain of Napoli for a period that lasted seven years (1984-1991) reflects Sorrentino‘s own childhood fascination and resulted in Maradona sending the Italian director a signed Argentina shirt after his mentioning of his name in the 2014 Academy Awards Ceremony.

The Italian master delivers an accurate rendition of his own recollections from his turbulent early years, while breathing life into a vivacious representation of life in Naples during the first half of the 1980s. This film is a first for Sorrentino in the sense that he features a teenager as the main character in lieu of an elder protagonist as he usually prefers, with Toni Servillo lurking in the background in the role of Fabietto’s father and Teresa Saponangelo playing the boy’s mother. The film includes some snippets from Sorrentino‘s youth, such as Fabietto’s brother auditions for a Fellini movie, an event that corresponds to reality. Regarding the question whether there will be a sequel to the Hand of God, Sorrentino responded that it is not in his immediate plans, but left an open window for the far future by saying: “Not now, maybe in 20 years”.