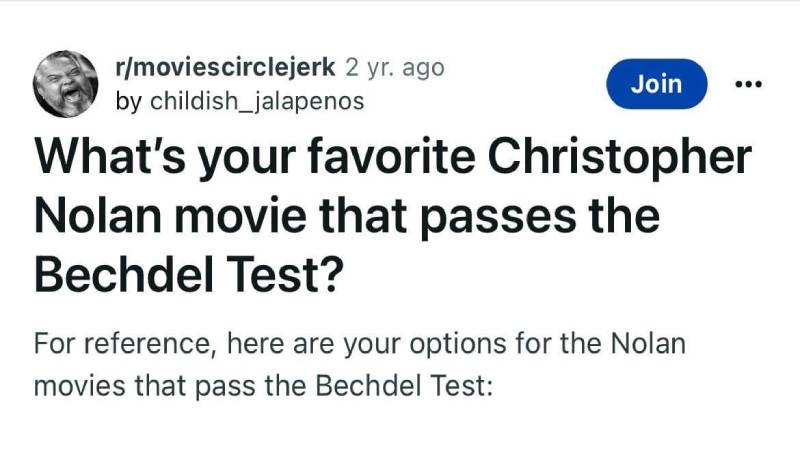

Within just a couple of days of its release in cinemas worldwide on Friday, July 21st, Christopher Nolan’s Oppenheimer widespread accusations of sexism. Some critics noted the that first female character only speaks after 20 minutes into the film, and then someone immediately has sex with her. Face the inevitable consequences of opening your month, babe! Others pointed out that the film fails the Bechdel Test. This is indeed true. Despite the presence of three significant female characters, they never talk to each other at all. Oppenheimer’s lover Jean Tatlock is played by Florence Pugh (pictured above), while his wife Kitty is played by Emily Blunt, and his sister-in-law Jackie by Emma Dumont. The cast includes nine female characters, against 119 males (according to IMDB). A disgruntled viewer slammed the “blow-up doll” treatment that these women received. Another one joked, while also extending the comment to Nolan’s entire filmography:

.

.

.

According to various sources, there is not one single scene in Christopher Nolan’s entire filmography of 12 movies in which two (or more) women talk to each other about anything other than men.

.

This is what Victoria Luxford (who wrote our review of Oppenheimer) has to say:

.

“I’m wary of any metric that takes nuance or storytelling out of the equation – by the strict rules of the Bechdel Test, The Room [Tommy Wiseau, 2003] is a better film that The Godfather [Francis Ford Copolla, 1972 ]. Allison Bechdel herself says she never intended the comic strip to be adopted as a doctrine.

For Oppenheimer itself, I think the articles implying the film is sexist is a stretch. Florence Pugh’s character is a psychiatrist who is shown to be in her own field on Oppenheimer’s level in terms of intellect. Did she need to spend most of her time nude? Probably not, but I think to focus on that is dismissing some interesting dimensions to their relationship.

Equally, Emily Blunt’s character, Oppenheimer’s wife, is shown to be equal to the men questioning her in the latter stages of the film. She’s shown to be morally stronger than her husband in almost every aspect.

It’s true that they are angry, frustrated, troubled people, partly because of the position society puts them in. I would say this is period – accurate. It’s the 1940s, and these are women kept from decision making roles, particularly in this space. Nolan reflects this in a small moment where Olivia Thirlby’s character is irritated that security assumes she is a typist and not one of the scientists.

My personal opinion, both as a woman and as a film lover, is that with films such as these there seems to be a need for people to have a strong reaction, even if it’s based on shaky ground.

As with the argument that Barbie [Great Gerwig’s other half of the Barbenheimer duo, released on the same day as Nolan’s film] is ‘anti-men’, I would say that calling Oppenheimer a poor representation of women is a point that relies on ignoring a lot of nuance.”