In July 2020, the editor of DMovies Victor Fraga and the editor of Doesn’t Exist Alex Babboni got together in order to interview Peter Greenaway. The running piece was published in early 2021. Below is the long version of the interview:

You can buy the print and the online of Doesn’t Exist’s tribute to Peter Greenaway by clicking here.

…

.

Alex Babboni – Doesn’t Exist is a publication about fashion and cinema. What do you look for in a magazine?

Peter Greenaway – A magazine, because of this sort of notion, unlike a film – well it’s not really true nowadays – you can freeze a frame. You could easily freeze a frame in a magazine, but I like this sort of see-through [a magazine]. I don’t know whether each page has to relate to the next page, that it has to be narratives within narratives within narratives. In a way, it’s sort of like… a magazine, I suppose… I must be careful with my metaphors, like a ‘static interactive film’.

AB – Your work comes from a painting background.

PG – At the tender, naïve age of 13, I wanted to be a painter. I was in art school in 1960, a hell of a long-time ago, and that was the big first splurge of the first generation after World War II that began to develop identities. It was the time of Carnaby Street, the Swinging ’60s – sorry to use a cliché – but it was about lifestyle. I was in art school with Keith Richards and Ian Dury; I went to art school with a whole load of people who ostensibly wanted to be painters, but they all came out as fashion designers or…

AB – Would you say that painting is pivotal in your career?

PG – I think probably if you would have run through a list of all the people who were in my generation, not one of them is a painter-painter, in a sense that we have to be careful about definitions of painting now. Marcel Duchamp said that “anything you want to regard as a painting is a painting”. But those people have lived a life that’s related way back to painting and I think painting is the most important thing that exists on the planet, even more so than text.

AB – Visual literacy, as you like to emphasise.

PG – Text is secondary to the notion of image. It’s how it says in Genesis, “in the beginning was the word”: this is a lot of rubbish. How can Adam go out into the world as God commanded and name everything unless there is something to name? So, in the beginning was the image! And I think that this stands for everything in our culture.

Victor Fraga – Are you arguing that the narrative is subordinate to the visuals?

PG – Let’s get this straight: I’m anti-narrative. Narrative is totally, totally unnecessary. You have to have systems, of course, you know, “one, two, three, four, five, six, seven, eight, nine, 10” is a good enough narrative for me. Although “10, nine, eight, seven, six, five, four, three, two, one” is an even better narrative. You have to worry about structures and about the cinematic process through time. Of course you have to worry about beginnings, middles and ends, but I don’t think that structure has to be narrative. It’s our comfort zone: we all go around telling narratives all the time. But in cinema it’s not necessary. I’m very happy that it exists in book form, literature form.

VF – Is this the very essence of cinema or is this just Peter Greenaway?

PG – A narrative for me is really essentially the phenomenon of text. We’ve learnt how to express ourselves narratively. Neanderthals living in a cave no doubt told one another stories, but as soon as the notion of writing, the world’s organisational space began… all about text, text, text, then the development of narrative flourished. It’s quite possible, and there are many examples that we can talk about them, and I’m striving all the time to try and push my cinema in that direction: I sincerely believe that cinema should be non-narrative. The very, very best painting is not narrative. The best painting does not tell a story, it doesn’t have to tell a story!

VF – Yet most paintings seem to tell some sort of story…

PG – Because most painting is narrative, most painting is reportage. Most painting is affixed to the notion indeed of representing the real world. But if you get rid of narrative, you get rid of that functionality the painting has been so responsible for. The big irony is that right about until Monet, probably in London in 1861, all painting was narrative. Monet started making paintings without a narrative, essentially for the first time. And he broke the bank: thank God he did it! Extraordinary painters followed him in the 20th century – Malevich, Kandinsky and Mondrian –, creating the only really sensible painting that should ever exist. That’s when all notions of reportage began to disappear from painting, and we entered what, I sincerely believe, is the most important century of painting we’ve ever had: 20th century.

VF – And what happened after that?

PG – After that in painting we did not have to illustrate [texts] anymore. To me, ‘illustration’ is a dirty word because it is secondary. It’s not the prime motivation to illustrate something, it is to try and make an image to stick to something that already exists in another medium, and I know my detractors find it very difficult to stand this. We sympathise with it because cinema is a medium for all seasons, it embraces absolutely everything. Just think of those who have to make a huge variety of disciplines, fomented text… I don’t think there are many films which are really films. Most cinema we’ve seen so far, since 1895, has been some form of illustrated text. It could be said, maybe pushing the boat out here, in a melancholy moment, cinema is over 120 years of illustrated texts: Bollywood and Hollywood are absolute examples of this. I cannot really go to very many producers with a bunch of images, a collection of paintings and say, “Give me the money”. They really don’t know what the hell I’m talking about; they need a word, a text, a literary form to be able to raise the money to help me make a film.

VF – Who was it that came close to making non-narrative cinema? Was it Resnais, was it Godard?

PG – Well, Resnais is my real hero. I’m a great fan of all the Nouvelle Vague people but I suppose we could revere Alain Resnais. The greatest film of the last 50 years, maybe even longer, is “Last Year in Marienbad”. That’s a film that really separates the sheep from the wolves. Huge numbers of people find it to be pompous, wholly intellectual, etc. But that’s the closest film I’ve ever seen that’s come to ‘non-narrativity’ in a way. Even though it is scripted from an amazing novel called Jealousy by Alain Robbe-Grillet. Last Year in Marienbad (1961), I suppose, he hangs over the early part of my film career as the number one.

VF – Are all of your favourite filmmakers European and avant-garde?

PG – Don’t get me wrong, if you want to ask me who my favourite commercial film director would be, I would say it’s that extraordinary Englishman [Ridley Scott] who made Alien (1979) and two other big films that have satisfied critical appraisal: Blade Runner (1982) and Gladiator (2000). Very “Hollywood films” but extraordinarily, amazingly visual… an amazing imagination. I never quite understood: he’s highly respected but he’s still not really up there in the great echelon of great filmmakers.

VF – But Blade Runner is considered a watershed, the first postmodern film ever made. And I would argue that you too are a postmodern filmmaker. Wouldn’t you agree with me?

PG – First, I am not sure, it’s a portmanteau word. We drag it out of the closet and find something that doesn’t normally fit the other categories.

VF – What I mean is, you blend styles in a smooth and seamless way.

PG – No, I am very much interested in the language of cinema. As I explained before, I’m not particularly interested in telling stories, as I think there are more profound ways in which to attach ourselves to a human predicament.

VF – What about Godard’s latest film “Le Livre d’Image”. It’s a wordplay in French meaning “the image book” and also “the free image”. Is that a non-narrative film?

PG – Yes, it is. However, I think it’s rather boring, I’m afraid. I certainly believe in the pleasure principle: you have to entertain. Vitruvius, a Roman architect said that every great work of art has to be 50% entertainment and 50% instruction. And I think that’s what we all ought to aim for. If it’s merely entertainment, like Hollywood, you’ll have forgotten it by tomorrow afternoon. If it’s only instruction, people will be so bored they walk away. You got to find a way to put these two things together.

VF – Do you consider yourself a multimedia artist?

PG – I see all arts as a multimedia activity. The magazine proves it: image and text. How to make a table, how to cook a pie, it’s everything: it’s all one phenomenon. And I think that very short-lived idea of life by Keats, the romantics, from Jane Austen to Napoleon, I don’t think anybody believes that anymore.

VF – You obviously have a huge affinity with Rembrandt and the Dutch masters. Could you please talk about your connection to them?

PG – Rembrandt became very wealthy, although he lost it in the end because he was such a bad manager of money. But he found a way to do what he really wanted to do. It is 1600 to 1700, the breakaway time. Perhaps not as important as Monet – when painting became painting and not illustrated text. Still, Rembrandt developed the ability to be represented by his own curiosity.

VF – Is this ability “to do what you really want” an individual trait?

PG – That’s indicative of Holland in general. We really have to talk about the major cities, of course. If you go out in the sticks, they are still farming, looking after cows – a lot of them still do. There are more cows than people in Holland. It’s a bourgeois phenomenon, the middle-class who begins to become educated. For example, the first educated females in the world were Dutch. Because they were all Lutherans and Calvinists, actually more Calvin than Luther, it was important that everybody should read their Bible. All females from the tender age of three or four started to learn how to read. And as soon as you start reading you don’t just get stuck on Genesis, you read everything else! There was a huge number of educated females, they were the ‘business people’: they kept the books and read what was necessary.

VF – They definitely don’t sound like “good Catholic girls”!

PG – There were lots of Roman Catholics in this city [Amsterdam] and they hated it. Catholicism is against knowledge: “don’t get females reading: they get too many ideas.” This city was the centre of female learning. And 51% of the world’s population from the last 3,000 years has been female and that’s really important. It’s the beginning… the pre-establishment of the age of Enlightenment.

VF – This could be an interesting theme for a movie.

PG – I have been trying to get a film off the ground for a long time: three people live in this city not far from where I live. Firstly Spinoza, representing the beginning of atheism – it is really exciting that the first pronounced atheist was a Jew: he lived in Street Number One, let’s call it that. Rembrandt lived in Street Number Two: he’s very pro-Jewish, most of his portraits are of Jewish people, so there’s a connection there as well. And then there’s Street Number Three around the corner: René Descartes – and I have a statue of him outside my house. He couldn’t stand the French because they were Roman Catholic and very conservative, so he comes to Holland and lives in Rotterdam, then lives in this city in Street Number Three. These three people are responsible, in a curious way, for our world: atheism… you know, Christianity and behind it all the other religions that would collapse as well. And then Descartes’s “I think therefore I am”. It’s the beginning of the new understanding and intellectual reasoning position. Rembrandt is the precursor of 19th century Impressionism, the notion of perceiving reality in different ways.

VF – It sounds like a lovely trilogy of faith.

PG – I wanted to make a film about Descartes. He fell in love with a young man here in Amsterdam, a soldier, and he had to keep it very quiet, of course. He was also involved with the daughter of another Dutch woman. You might know his story: he was summoned to Stockholm to set up a salon for the Queen of Denmark. Descartes was used to staying in bed until 12pm because he got most of his good ideas in bed in the early morning. A woman woke him up at 5am every morning and the poor guy caught a cold and died. Her name was Catherine, she was a protestant, though she eventually became a Catholic, being invited back into the Church. So, he died in Denmark. That’s a great story about his death: his head was taken off his body, decapitated. Someone wanted it as some sort of totemic representation of the greatest intellectual in Europe at that time. It’s interesting that Descartes had this complicated sex life and I seriously want to make a film about it. And like I said before, Spinoza, Descartes and Rembrandt all lived in this city within three streets of one other. They represent beginnings of atheism, the beginnings of empiricism and the beginnings of painting.

VF – Does this triptych still stand today?

PG – We now live in a post-Duchamp era, rather than a post-impressionist world. But there’s a huge opening of doors. These three people created the 20th century; it all happened here in Amsterdam.

VF – How long have you lived in Holland?

PG – I’ve lived in Holland for 26 years and I’ve had a Dutch producer for nearly five decades. I’ll tell you the anecdote, you probably heard it before: I was at the Venice Film Festival with a film I made called The Draughtsman’s Contract (1982), and I met this film producer called Kees Kasander and he said that, provided that I didn’t want to go to Hollywood, he would look after my film career.

VF – You also have a fondness for alphabetisation, numbering and cataloguing in general. One of our writers has said “if ever anyone were to make a film about the Dewey Decimal System”, it would be you. Is cinema defined by letters and numbers by nature or is this a creative choice?

PG – You know… 16mm, 35mm, 9.5, Godard’s “the truth is cinema on 24 frames per second”: that’s all numerical game playing. And there are one or two underground filmmakers who continue to play with that. Have you come across a filmmaker called David Rose? His films are all about figures. You have just given me the opportunity to expand on being non-narrative but I have to have structure. And there are all sorts of structures in the world, which are going to allow me to do that.

VF – David Rose is to numbers what Greenaway is to game-playing. Correct?

PG – Have you ever seen Drowning by Numbers (1988)? Again, it’s numbers one to 100. You can forget the numbers, if you want. There are all sorts of other things in that film, as the number 33 is written on the back of a bee which is flying around. And you’ve got to be incredibly careful to see that. I get accused of leaving numbers out, but I can assure you they are all there. If they are not there in the image, they are there in the sounds or in the music, somewhere.

VF – Who created these numbers?

PG – The number counts, which are now universal, are basically European and Napoleonic. He devised an early idea of the metre, everything based on the number 10. Before that, there were thousands of others. But there are all sorts of different systems. We happen to be living in 2020 but that’s rather obscure, don’t you think? Let’s get rid of that and start again, not this stupid idea of Christ’s birth creating this numerical system: first man on the moon is year zero. We should start counting again. And all these old systems, you know, if you look at the Middle East, they all start again at a certain period. The Jewish restarted three times, I think, calendars in Baghdad started from scratch, because when you get to too big numbers, it becomes uncomfortable. I’m writing a massive project and it’s all about renumbering the world; it starts all over again.

VF – You won’t be using the decimal system, will you?

PG – There are other number systems, there is the alphabet. The Chinese now, they’ve joined the modern world, and all their books now are alphabetically sorted, from A to Z. And the alphabet is incredibly important. Your name must be mentioned in thousands of different indexes, apart from Wikipedia – we’re all connected to that. When the Jews were in the concentration camps, they all had numbers and figures on their arms: they were all labelled with a number. There’s another huge area of playing with structure. A lot of my structures have been alphabetical and numerical and, also, there are themes like platonic solids and geometric Euclidean ideas. Plus, the whole scientific world is now very much based on Einstein’s language, which is very obscure to most. Do you understand the equations that got us to relativity? Very difficult to find out. But there’s also all sorts of algebraic systems across the equal sign.

VF – Which such system is most compatible with cinema?

PG – What I’m trying to find all the time is a system whereby I can play games – and the English are very good at playing games, they invented most of them but they don’t play them very well anymore – that game-playing activity, if you like. I use the word ‘game’ very loosely here but there is a rationale. Most new inventions – Leonardo da Vinci is a supreme example – are very forward risk-taking. ‘Let’s go there and explore it’ kind of stuff. We’re now on the Moon and you have a computer because of that game-playing and I’m interested in that. I remember a UK magazine once saying that “Greenaway is a game player: he just plays with things, he’s not serious”. But I think that game-playing is a very, very serious occupation, and it’s got us computers, and it’s got us to the Moon.

VF – Are you a game-player, a titillator and a provocateur?

PG – Being very English, it’s deeply ironic. There is no meaning. Any meaning we can find is a meaning we have to invent for ourselves.

VF – You started your career by making educational documentaries for the Central Office of Information. Would you agree that your films have changed since and that, instead of educating, you often wish to dazzle and challenge your audiences?

PG – The COI, the Central Office of Information – which sounds like a Russian politburo and there were elements of that in it – was a form of wartime propaganda machine. Germany had a brilliant propagandist and his name was Goebbels. The English wanted something equivalent based upon his structures and his methods of propaganda. They developed what was once upon a time called – since so many English things are royalist – the Crown Film Unit, and that became the Powerpoint, the propaganda. And it had so many sorts of luminaries – many of which I’m sure you know – famous poets, W. H. Auden, John Grierson, a lot of composers… they were all part of that patriotic working, you know, to defend ourselves against the Nazis. But then came peace: what was the unity going to do or going to organise? The COI lost its purpose. Just at that particular time, the British Empire was collapsing, for good or for bad, and a lot of people hated it. Well, it turned out to have been absolutely necessary. They were all being educated and they wanted material: primarily for television and also for their own film businesses.

VF – I can’t imagine you being a very devoted patriot.

PG – Well, I was a keen Marxist, Leninist and socialist those days. I went out of my way wearing red shirts. I cut all the propaganda for the Socialist Party. There was a long-time serving Prime Minister called Wilson. “No Mr. Wilson, No Mr. Heath”. I am not as politically active now as I was then. I was aware that the COI films were propaganda and people were telling you lies dressed up in sugar. And that’s why I made so many mockumentaries: I made Dear Phone (1976) about making phone calls but all the information was wrong. That’s when The Falls (1980) came, and then Act of God (1980) about people being struck by lightning. I was looking deliberately for an ungovernable phenomenon, like being struck by lightning. If you go out to a golf course carrying a metal stick, watch out, you’re asking for trouble. But if you go to Argentina there are graveyards of children killed by lightning strikes.

VF – But Act of God isn’t set in Argentina. How did you go about finding the UK victims?

PG – We put advertisements on English newspapers looking for people who had been struck by lightning and survived, so that they could tell us about their experiences. A hundred years ago, people called it an act of God because “you had been evil, you had been picked out to be eradicated from the Earth”. We now know that to be absolutely stupid but a lot of people – even in the English countryside – still believe that if they behaved better, they would never be struck by God. It’s all about suspicion and superstition and bad ideas.

VF – Are all the events in Act of God real?

PG – The Falls was entirely bogus and also connected to the notion that we all, historically and geographically, want to fly. It’s a universal mythology that we all desire and, in a peculiar way and thanks to machinery, we can. But I still can’t simply lift off the world: it’s just never, never going to happen, we’re just anatomically ill-prepared for that. But they actually felt that it [flying] was true and they thought the film Act of God was false. What is false can be easily considered true, what is true can be easily considered false and I enjoy that. And if you ask me what did I do at the COI? It gave me that incredible, dare I say, cynicism. Cynicism is probably very bad for the human spirit but it gives you a deep sense of irony.

VF – Please tell us about your writing.

PG – I’ve written many novels, most of them are unpublished. I write a lot! Although I’m supposed to be a picturesmith, all of my scripts – and I’ve made 60 films – are always my films. Nobody else’s script, nobody else’s idea. Unfortunately I cannot write music but I do everything else.

VF – You and Michael Nyman worked together for about 15 years. Would you like to reflect on the nature of your working relationship and what made it so successful? I would argue that one without the other is an amputee, much like Andréa Ferréol’s character in A Zed & Two Noughts (1985).

PG – They said the same thing about Sacha Vierny, Alain Resnais’s cameraman, who also worked with Buñuel and so on. And they said there would be no Peter Greenaway without Vierny but most marriages end in divorce. All these film myths are interesting. You have to understand that Michael Nyman and I had an enormous falling out, a massive divorce. We were incredibly close collaborators, our wives were friends, our kids went to the same school, etc. The last film we did together was Prospero’s Books (1991).

VF – Let’s talk about sex and death.

PG – Well, there’s nothing else to talk about, is there? If we are going to talk about sex and death, nothing else is important. Balzac suggested that money was important but money hasn’t been around for very long, has it? About 4,000 years. But every evidence suggests that it doesn’t make people happy. You can’t take it with you when you go. At the other end, what I think is that “power is more important” – and that’s Shakespeare: his plays are all about power, however you play it. But isn’t the business of sex and death to do with the manipulation of power? We’re all shit-scared to die and ‘how could the world go on without us?’. Power is indeed about life and death. I’m not even going to talk about love and Darwinian concerns. It’s the very, very beginning and the very, very ending which are both unknown and this is at the heart of all of our anxieties.

VF – Sex and death have always been intimately connected in your films. Have your views on these topics changed over the decades? In other words, do the 40-year-old Peter Greenaway and the 78-year-old Peter Greenaway perceive sex and death in the same way?

PG – You’ve given me the absolute forum for what I’m totally convinced. I’m 78 now and the average age of death in Holland is 84, even for foreigners, so if I’m lucky and have five more years, I’m very conscious of that. Let’s be a little intellectually snobbish: Eros and Thanatos. The Greeks were concerned about this thousands and thousands of years ago, the very beginning and the very end. As a young man I made a lot of films about sex, concomitant notions. You’ve seen “The Belly of an Architect”? The story is nine months long, it begins with a fuck and ends with a death. But the moment now is much more Thanatos: we’re waiting, and the coronavirus interrupted the wait, to make a film with Morgan Freeman called “Lucca Mortis”. It’s all about death.

VF – Is it about Puccini?

PG – No, Puccini is in it – because he happens to be born in Lucca – but he’s really minor. It’s just an excuse to use the scene from Madame Butterfly and to have a man going around smoking a cigarette. There’s a very famous statue of Puccini smoking a cigarette in Lucca. I really like the idea of the feature film as an essay. Have you seen [Jonathan Demme’s] Swimming to Cambodia (1987) and [Louis Malle’s] My Dinner with Andre (1981)? They are feature films as essays. But I think, in a peculiar way, all of my films are about essays. The Cook, the Thief, His Wife & Her Lover (1989) is much about materialism per se, capitalised by the notion of cannibalism. It is a discussion about what happens if we eat ourselves. There are people around a table in a restaurant talking about different things. I want to go back to this trivial idea that you have to entertain. The Draughtsman’s Contract is about what is and what isn’t true, illusion and reality. I could go through all of my movies and say “this is a documentary”, or “this is a documentary in feature film form” and so on. But I don’t think that’s necessary: is there much difference nowadays between a feature film and a documentary?

VF – The line between feature and documentary is indeed increasingly blurred. Maybe people have become desensitised to the truth?

PG – In all countries, you need to have a script in order to get funding before you make a documentary. That’s ridiculous, isn’t it? Isn’t that entirely counterproductive? Documentaries are supposed to be lively as it is: you, as an outsider, are just supposed to be observing it. Ok, you have to fashion it, you need to have a structure but you also have to write a script for a documentary, so there isn’t much difference [to fiction]. You bend the world according to preconceived ideas and that’s not what a documentary is about.

VF – Not all documentarists are like this. Brazilian documentarist Eduardo Coutinho didn’t know what his documentary was about when he started making it, and often the documentary was about the process of documentary-making.

PG – Well, I could use that definition in my process when I make a feature film: I don’t really know what I’m going to do when I start, and it’s likely because of my painting background. When painters begin, they often don’t know what will end up on their canvas, and that’s what’s so incredibly exciting. I think my early films, the mockumentaries, such as “The Falls”, are about what you can find and what you can fashion.

VF – Your films feature abundant nudity. Yet you never show real sex, unlike filmmakers such as Lars von Trier, Gaspar Noé and your countrysake Michael Winterbottom. Why is that?

PG – Certain people have a great problem with that… maybe actors are the most difficult people of all. I’ve actually tried to present the real sexual act and people would say: “What are you doing here? Where’s the pretence? Where’s the reality?” Just think of Don’t Look Now (Nicolas Roeg, 1973): the two lead characters, played by Donald Sutherland and Julie Christie, about them having real sex – come on, it’s just game play, part of the propaganda to distribute the film.

VF – Eight years ago, you said that you would kill yourself on your 80th birthday and that you couldn’t think of anyone who has done anything remotely useful past 80. Both Jean-Luc Godard and Alain Resnais made films into their late 80s and 90s. Have you changed your mind since?

PG – You speak Portuguese, right? Did you see the last 10 films of that Portuguese filmmaker who died at 107? They are all the same film.

VF – Manoel de Oliveira?

PG – They are very boring. It’s not just a question of turning the camera and making the same goddamn film.

VF – Well, you don’t have to kill yourself, do you? You wouldn’t dare to die before Godard, would you?

PG – Well, there are one or two good prints by Picasso that he did aged 82. Titian Tiziano in Italy probably painted his three best paintings when he was 84. Don’t worry, I have done all the research, I’ve worked it all out. But there are very few works of great significance done by anybody over 80. You take much younger people: you have to win an Olympic record in swimming when you are 13, because at 15 it’s already too late. All the famous runners or sports people are finished by the time they are 25 or 30. Eisenstein did everything in 1929 – that’s the famous year for him – he did absolutely everything when he was about 27, I think.

VF – Wasn’t he in his 30s during the Mexican odyssey portrayed in Eisenstein in Guanajuato (2015)?

PG – Of course he did things afterwards, but they were never as profound. If you think of Bertrand Russell, everything was finished by the time he was 35. All the mathematicians, all their great work is finished by the time they are 40. Risk-taking minds are related to creativity – I don’t think anyone can be surprised about that, can you?

VF – Is it true you are planning a follow-up of Eisenstein in Guanajuato?

PG – I got so excited and interested and delighted by Elmer Bäck’s performance, I went away and made two more scripts with him. The Mexican film would be the third of three movies, the trilogy will be called Eisenstein on Travel because he was invited by Charlie Chaplin to come and make a film, as the Americans were astonished by Battleship Potemkin (Eisenstein, 1925). They had never seen something so violent, so quickly moving: you know, the speed of Russian editing is incredible, compared to slow Americans. And Stalin was interested. I remember the date was 1929, introducing sound cinema – and Russia didn’t have any sound cinema.

VF – So Stalin sent Eisenstein abroad?

PG – The Russians sent Vertov to Berlin and sent somebody else off to Paris, I can’t remember his name. They sent Eisenstein, alongside Alexandrov, who also had a reputation as a filmmaker, to Hollywood – the centre of Western filmmaking – to learn about sound cinema. Not that they came back with any knowledge, but Eisenstein was very happy to learn about Europe. He stopped off in Paris for a long time and he stopped off in a place in Switzerland very close to Geneva and Lausanne, where the very first film festival in the world was held. We’re talking 1929.

VF – I always thought that the first film festival in the world was the one in Venice, that is interesting.

PG – A place called La Sarraz, and it was attended by many important experimental filmmakers of the time, and the most important guest was Eisenstein.

VF – It no longer exists?

PG – No. It was in a castle. There was a Swiss patroness who wanted to turn her castle into a salon for European culture. The first year she based it on music, so Stravinsky and other luminaries of the period had a 10-day festival. The second year she based it on architects: Le Corbusier went. The third year she invited film directors, and Vertov was invited. He was going to be the ideal Russian but could not make it: he was making a film somewhere, so Eisenstein muscled himself in. Being very articulate, volatile and excitable, he very rapidly took over the festival.

VF – Flamboyant as well, wasn’t he?

PG – Indeed, a great raconteur, he spoke about eight languages. We want to make the first film about “Eisenstein in Switzerland” – that was the original title.

VF – So Eisenstein became a posterboy for the Soviet Union?

PG – I find it fascinating because he met everybody who was of significance: he met all of the Russians – he used to have breakfast with Stalin –, but he also met all the people in the politburo. And he met famous people in Stalinesque society. I am amazed, and most other people probably are too, that he didn’t end up in Siberia: he was very close to the nail many, many times. And Stalin always thought he was a filmmaker, but then he started remaking all these films. Eisenstein moved away and his first port-of-call was Berlin, where he met all the famous Germans: Marlene Dietrich, Josef von Sternberg, everybody. He met Jean Epstein, Einstein, Picasso – he met anybody who was somebody in the late ’20s.

VF – What about Fritz Lang, F. W. Murnau?

PG – He met all of these people and all the French guys: the underground filmmakers, the politicians, the artists and all the writers. We could put together a list of 100 famous people he met and we’ve started off a documentary and called it “The Eisenstein Handshakes”. Each film is five minutes long with all these people that he met. Then he went to Hollywood, where he met Chaplin, who was a communist, and he met all the famous Hollywood producers. Oh, you name it, he just met everybody! The impact made by The Battleship Potemkin all over the world was just incredible, a real bombshell. No one had ever made a film like that before: cut very fast, very different from anything else. Do you remember the revolution on board of the ship where they had to eat bad meat?

VF – Full of maggots.

PG – Yes, that’s right. Even on his way [to Hollywood], Eisenstein became good friends with Chaplin: he used to swim in his pool and play tennis. Eisenstein put up about 20 different projects but they were just too ‘way out’ for Chaplin. Intellectuals have never been successful in Hollywood, as you know. Chaplin suggested, along with Robert Flaherty, that Eisenstein should go to Mexico to make an ethnographic film about the advent of the Europeans into Aztec and Mayan cultures. He planned this film which would be called Que Viva Mexico!. He went there and he was supported by left wing socialist-leaning American millionaires, but the money wasn’t really enough. In the end, I think Eisenstein was very above and beyond the top, with 30 miles of film to make. It all fell apart: Stalin got angry and wanted him back again, so the whole thing collapsed.

VF – As a trilogy, how are you planning to present it?

PG – The first part is the big film festival, Eisenstein in Switzerland, and Eisenstein in Hollywood is the second one, where he comes up against all those Hollywood directors who said: “Brilliant Mr. Eisenstein, brilliant. You can never make these extraordinary films here.”

VF – The Russians frowned upon the depiction of Eisenstein’s homosexuality in Eisenstein in Guanajuato. Do you intend to address his sexuality in the other films?

PG – Eisenstein was a homosexual, he was interested in his own sexuality and these were very difficult times. Part of his sexual education was to travel across Europe. He was really fascinated by the novelist, playwright, poet and art collector Gertrude Stein – a lesbian in Paris around 1929. And he was also interested in people like Jean Cocteau, who was also a flamboyant homosexual. You know, the so-called ‘emancipated’ people… Stravinsky too was bisexual – nothing surprising in retrospect, most figures of the Renaissance were atheists.

VF – Is there a connection between homosexuality and atheism?

PG – We’re beginning to realise that most of the Renaissance figures were atheists – they didn’t dare say it because they’d end up on a stick. Leonardo da Vinci was certainly gay and very careful about expressing his political and sexual opinions. Michelangelo was a homosexual but, again, he was very circumspect about saying it. All these people… [Girolamo] Savonarola and [Niccolò] Machiavelli. It was certain death to express your atheism and the same for your sexual predilections throughout the 16th century. Voltaire was gay as well. Shakespeare probably… certainly was gay. You know, it was the status quo, it was the sensible, reasonable thing to be! [laughs]

VF – Could you please talk about the role of costumes in your films? Is it correct to say that they have a life of their own and that they are characters per se?

PG – You are thinking of The Cook, the Thief, His Wife & Her Lover probably.

VF – Also The Draughtsman’s Contract… the main character is wearing black while others wear white, all of a sudden it all switches around.

PG – Yes, there is that. It’s an indication of getting things wrong, of being inside or outside the establishment, etc, playing the game. You know the statue in The Draughstman’s Contract, he’s only understood by innocence, people are always outside the mainstream, I’m playing with all this sort of ideas too.

VF – You are a friend of Vivienne Westwood, yet I don’t remember you working together. Is this correct?

PG – We wanted to get Vivienne Westwood to design the costumes for Rembrandt but that didn’t happen. She’s an extraordinary woman, very, very bizarre. I remember having long conversations about Sophocles with her and how she reckoned I got everything wrong about him – and she was probably right! Very autodidactic. Everything is picked up through the world, book-reading, and she hasn’t had much of an official education, whatever that means. Vivienne was very familiar with the very famous painting just down the road from here, Rembrandt’s The Night Watch. It’s an extraordinary painting but very bourgeois: it’s related again to the idea of the bourgeois. Not about the aristocrats, not about the Church, but the people who have lived here dressed up in army uniforms pretending to be patriotic and fight for the Dutch. In some curious way, it’s a copy of a Velázquez painting.

VF – Perhaps Rembrandt was the one pretending to be patriotic?

PG – Do you know what’s very strange about the Dutch? They are very free-thinking and liberally free but all their baker shops are full of Iberian imagery! Sometimes there are rivers running through the countryside, one side is protestant and the other is Spanish – even now in 2020. They are supposed to have given this stuff away years ago but it’s still deeply inbred. Very Calvinist, when you walk down the street at night no one closes their curtain because, as a Calvinist, the worst sin that you can have is envy – people have to know what you got. If you own a Rolls Royce or a fur coat, you get spat on in the street because that’s a sign of exuberance, you know, as in The Embarrassment of Riches, the book by [Simon] Schama. We are kangaroo-hopping, jumping from subject to subject… what were we talking about just now?

VF – Costumes!

PG – Stendhal syndrome! I took Vivienne Westwood to the Rijksmuseum to see Rembrandt’s The Night Watch and she started giggling. She couldn’t stop giggling. It wasn’t Stendhal syndrome exactly but it was the nervousness, a sort of “hey look, I’m in front of this extraordinary, famous painting”. The people at the museum told me: “could you please take this lady out of the room, she’s disturbing everyone”. The shock of seeing something that you thought you knew extremely well but “hang on, I don’t really know it that well!. And it’s a big surprise when you really do see it. I had that with The Last Supper”by da Vinci: I spent a lot of time in front of it. The echoes are still applying and we’re working now on the idea of what is true and what is false.

VF – Any final thoughts about costumes and the role that they play?

PG – I think they are important, you know, we sat down with Jean Paul Gaultier, we looked at paintings and tried to find – I don’t know the right word for it – this sort of parallel universe. The Cook, the Thief, His Wife & Her Lover is all about thievery and vulgarity. And there’s a whole series of paintings about the Civil War that Holland fought against Spain. There was no regular army here so you had to pay for your own costumes: those who were rich dressed much greater than those who were poor. And we talked about this to Gaultier and he was entertained by the idea and took direct motifs to the restaurant, to the waitresses, forks and knives, all over them – but then that’s maybe another side issue. I organised the painting space as a cinema space with the camera man to be a pastiche of a Civil War painting. If you want, you can see the tableaux vivants: the sashes, the high boots, etc. It’s contemporary, exhibitionist contemporary.

VF – They sound as fake as the “patriots” in Rembrandt’s painting?

PG – There is always this concern for the notion of how you look, why you look and how you present yourself: it’s inevitable. I’m fascinated about that! We are who we eat, we are who we read, we are who we dress.

VF – You once said that the remote control spelt the death of cinema. How do you feel about streaming?

PG – I think that cinema is dying very rapidly now, it’s becoming wallpaper. Do you watch your wallpaper? There’s a huge amount of films being made, more than ever before, but who’s looking at it?

VF – Would you describe what Netflix shows as film?

PG – There’s another thing about that: it was devised to be a long form cinematic activity, but do you really know many people that follow a whole series through?

VF – A lot of people!

PG – I give up with that kind of stuff. David Lynch started it with Twin Peaks. Who finished Twin Peaks? Very few people. There’s something exciting about the concept but not very useful in terms of the actual management. I’ve got really stuck on The Ozark [Netflix], but suddenly I stopped being excited and didn’t want to know anymore.

AB – Regarding your very own career, do you have any favourite films?

PG – A Zed & Two Noughts. They say your second film is the most difficult film of your life: “you make a film and if it’s successful…”

VF – That’s my favourite, too! But isn’t that your third film, after The Falls and The Draughtsman’s Contract?

PG – Yes, but I always think of The Draughtsman’s Contract as the first film that I made. The second was A Zed & Two Noughts, and the third was The Belly of an Architect (1987).

AB – Why is this one your favourite in particular?

PG – A Zed & Two Noughts is the most complicated, evolved and intellectually complex movie. It’s been called ‘three films that pretend to be one film’. It’s a film about the world as an arc. It’s about doppelgangers: how the hell would we behave if we met ourselves? And thirdly, which is perhaps a little more elitist and academic: it’s about the alphabet, 26 different ways to make a film.

AB – The 26 letters of the alphabet.

PG – Sacha Vierny and I sat down and made a list: 26 different ways to light a film. You know, light and dark, noon and moonlight and starlight, and firelight, and television light, and even lighting by rainbows and it’s all there. There are three films there and they are all struggling to get out: they should be three separate movies.

VF – Would you change anything about the film?

PG – Let me put it this way: the best compliment I could pay to it is that it’s rather badly acted. And I was totally ripped off by Cronenberg who did Dead Ringers (1988): he sat me down in a hamburger bar and grilled me, like you’re grilling me about my cinema, then he went away and made Dead Ringers. If you look at Dead Ringers, it’s the same film but they have Jeremy Irons playing the part.

VF – The two brothers are not twins in real life, they are two years apart, is that right?

PG – That’s right, they’re not twins. And they weren’t very good actors either, you could see it.

AB – Any particularity about the costumes in A Zed & Two Noughts?

PG – I like the costume at the end: they made a costume for twins, an enormous two-piece suit.

VF – So why did you opt to have them in the nude at the end?

PG – Strip down to basics again: we’ve just seen a litany of animals and they’re all naked; they meet their deaths under some circumstances that make them part of mankind.

AB – How did you choose Jean Paul Gaultier for the The Cook, the Thief, His Wife & Her Lover?

PG – I used to work with a very good Dutch team: Jan Ross and Ben van Os. Actually, van Os was really responsible for the look of the film. The Cook, the Thief, His Wife & Her Lover was very much him.

AB – And the colour code, the way the same Helen Mirren costume changes, something that breaks the narrative, the continuity of the wardrobe …

PG – It was my idea to do the colour coding for The Cook, the Thief, His Wife & Her Lover and van Os followed it meticulously all the way through. I haven’t been so fortunate more recently. They always said: “Oh, Greenaway is a painter, he’s the one who designs what everything looks like. What time or space is there for an art director?”. But these guys have all the contacts, like you: if you are in the world of fashion, that’s an incredible activity!

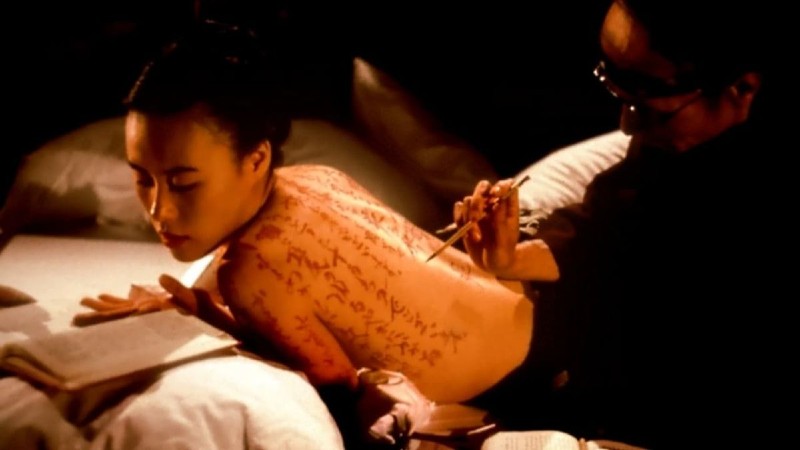

AB – Any other collaborations with fashion designers, apart from Gaultier and also Martin Margiela, who worked on the costumes for The Pillow Book (1996)?

PG – We’re supposed to be doing something with Stella McCartney but we really haven’t got ourselves together yet. But I’m sure we will.

AB – From fashion to films. It would be great to know your opinion about a couple of filmmakers: Federico Fellini, what do you think about his films?

PG – He’s extraordinary. Made some very bad films, we must not forget that Orchestra Rehearsal (1978) is an extremely bad film but 8 ½ (1963) is the most brilliant film about filmmaking ever done, I think.

AB – What do you think of Michelangelo Antonioni?

PG – Yes, a completely different filmmaker compared to Fellini.

AB – Stanley Kubrick?

PG – Very conventional filmmaker, I think. I liked it because he is like the sort of intellectual filmmaker, just slightly advanced from the pack, but not far enough.

AB – David Lynch?

PG – Yes, but I do feel that he started to make the same film over and over again.

VF – He hasn’t been making so many films.

PG – He is designing restaurants now. He is a painter originally, he returns to painting, I think.

VF – Andrei Tarkovsky?

PG – To be honest, I’m not a great fan of Tarkovsky. I find him quite boring. You sit around waiting and waiting and waiting for a magic moment, and you have to wait around for two hours! He was supported because he was a dissident, not because he was a good filmmaker.

VF – What about Mirror (1975)? That’s an entirely non-narrative movie!

PG – I would forgive him for playing with narrative if he wasn’t so boring!

VF – Let’s talk about Britain. What does it have to offer us now?

PG – I always thought Carol Reed’s The Third Man (1949) was a brilliant film.

VF – But what about the more recent stuff?

PG – I have to let you into a secret: I would rather go to a painting exhibition or read a book than go to a cinema. I think it’s a medium for children, I cannot believe in the ‘suspension of disbelief’.

VF – How was the relationship with Derek Jarman?

PG – There was a big love-hate relationship: we were always after the same money and you cannot cut the cake in so many different ways. Sally Porter was there at the time but I think the situation, because a lot of us were funded initially by Channel 4 and by the BFI, there wasn’t much money – but they were very supportive. We were all there at the same time but the BFI was often run very politically. Everybody who was a good Marxist socialist got the money. Then if you suddenly became a good fella, straight away: all the feminists got the money.

VF – Do you think François Truffaut was right when he said that there is an “incompatibility between British and cinema”?

PG – I think so, but he acknowledged British television, I think, or somebody else did. England is good with words but not with images; most of the early English painters were all foreigners, imported: people like Van Dyke, Rubens, etc. The first English painter is a man called [William] Hogarth but he was a caricaturist. I bet you couldn’t name three or four English painters who have been transported around the world. You have to wait until Napoleonic times: Turner was an extraordinary painter, perhaps not as powerful as John Constable, in the beginnings of Impressionism. You are going to have to work this one out: the biggest British painter recently dead would be Francis Bacon.

AB – Could you tell us about your next projects?

PG – As I said, if I listen to the statistics, I only have four more years to live so I want to get moving. I want to finish this Lucca Mortis with Morgan Freeman as soon as all the [coronavirus] masks get taken off, and I want to finish this film about Brancusi. But I also have a film about Oskar Kokoschka, an Austrian expressionist. There’s an extraordinary story about him: he fell in love with Alma Mahler, a famous Austrian composer. She was an extraordinary femme fatale and the founder of Bauhaus, Walter Gropius, was fascinated by her.

AB – Interesting subject: the sound, the painting, the operatic drama.

PG – Music is represented by Mahler, painting is represented by Oskar Kokoschka, the Bauhaus guy is the architect and ultimately he was fucked by a famous American writer. She was a sort of a muse to a whole series of people across the board. Oskar Kokoschka fell madly and carnally in love with her: they had an affair, she became pregnant and she aborted the child. He went to the abortion clinic, collected all the bloodied rags and kept them in his raincoat pocket for the rest of his life. But that wasn’t enough: he wanted to re-establish the relationship but she refused. So, he got Alma Mahler’s dresskeeper – this should fascinate you – a dress designer, to make a model of Alma Mahler, with all the right fuckable holes. She made this mannequin and Oskar Kokoschka lived with it for about two or three years: he painted it, and painted it, and painted it. Many paintings resulted from it. Of course, he had a sex life with it. Kokoschka happily has the initials OK and so I’ve called the film The OK Doll.

AB – And there is a fashion thread underlying it perhaps?

PG – Well, he’s Austrian. The big towns… the fascinating towns of Prague, Vienna, Stuttgart, all Austrian-architecturally designed. You know, the Succession building in Vienna, all the Klimt and Schiele atmosphere, very exciting to reproduce.

AB – What happened with the “model”?

PG – He lived with this model for a couple of years. First of all, he was so disappointed because Alma Mahler wouldn’t cohabit with him anymore that he went off to the German side to join WW1, and he got shot twice: once in the temple, which made him a bit crazy, and the other in the rib cage, where Jesus Christ was hit.

VF – Could you tell us about any future projects?

PG – I am supposed to be making a Welsh ghost story, a favourite piece of Wales, where I come from originally. I am supposed to be doing a Japanese ghost story. We have this da Vinci film to do. Oh, I have so many films to do.

VF – You’d better hurry up!

PG – I know! It takes a human gestation period, nine months, to make a film. If I’m very quick, I don’t know whether I’ll get through it all – but I don’t want to fall into the trap of the Portuguese filmmaker, making the same film 10 times in the past 10 years. Maybe it made him very happy, maybe he enjoyed being a filmmaker rather than making films.

VF – If you were young and beginning to make films now…

PG – I wouldn’t bother, cinema is dead! I would concentrate on my first ambition, which was to be a painter. Painting is far more important: it is the very first human activity we ever did. Cave painting 45,000 years ago in the south of France. We’ve only had cinema since 1895: that’s a drop in the ocean. And cinema is already dead and buried in a sense. It’s already moved on, passed on.

.

You can buy the print and the online of Doesn’t Exist’s tribute to Peter Greenaway by clicking here.