Known for his provocative statements, Peter Greenaway has repeatedly said that painting is the superior artform, most people are visually illiterate, cinema died in 1983 with the invention of the remote control and that “no student is allowed to pick up a camera until they’ve studied for three years.” He speaks from personal experience, having studied at art school for three years himself before segueing into film, combining his love of painting with time spent cutting movies for the UK Government’s Central Office of Information. He was disappointed that paintings did not have soundtracks. “So maybe what I make is not cinema, but paintings with soundtracks.”

Railing against what he calls the “Casablanca Syndrome” — the often studio-mandated requirement for all films to begin as text rather than image — Greenaway is a fierce advocate for non-narrative storytelling that prioritises the image above all else. Believing that we could’ve had a cinema of painters instead of writers, his own films have stretched the boundaries of what the form can and should do.

Much has been made of his use of painting as a means of artistic expression; taking the work of masters such as Vermeer, Rembrandt and Caravaggio and translating them into cinematic forms. Bringing painting to the film medium in a way beyond that of any other filmmaker, Greenaway uses the static image, the chiaroscuro, the use of artificial light, innumerable nudes, the excessively mannered tableau, the slow pan and the dense frame in order to expand the possibilities of cinematic language.

The writing is not on the wall

But the influence of painting is not used merely to make one marvel. It is also used as a way to obscure meaning while hiding it in plain sight. After all, a painting on its own is not a narrative object. Rather it is something one applies a narrative to. Like the heroes of The Draughtsman’s Contract (1982) and Nightwatching (2007; pictured below), we must study the frame for clues; for objects and gestures that hint at something larger, ostensibly taking place outside the painting itself.

Greenaway’s films are often as much about what you don’t see as what you do. A Zed and Two Noughts (1985) tells us that you never see a female leg in a Vermeer. Meanwhile, The Belly of an Architect (1987) reminds us that Rome’s glory on the world stage is due to it being in ruins rather than immaculately maintained. Likewise, as we learn The Draughtsman’s Contract: “A painter cannot be too intelligent. He must always be blind to certain events.” In this respect, his movies are immensely self-reflexive, positing the idea that even he, an audiovisual painter, cannot explain the meaning of his work. Communing with the masters of old, they are the beginning of a never-ending dialogue rather than its end-point.

Connecting the puzzle pieces

A great example of this delightful puzzle-making can be found in his first feature film, the dazzling, maddeningly Borgesian The Falls (1980). Following on nicely from the mockumentary style of early shorts such as Vertical Features Remake (1978) and Dear Phone (1976), it tells a BBC-parodying tale of 92 people whose name start with Fall struck by the VUE, otherwise known as the “Vertical Unknown Event”. Across many of these 92, often-contrasting, tales, characters lay out their theories behind why people were suddenly transformed into bird-like creatures. One analysis stands out. The Italian Coppice Fallbatteo believes the secret lies in the Brera Madonna by Piero della Francesca; specifically, the ostrich egg at the centre, an emblem of Mother Mary’s fertility and a promise of immortality. Situated within an arch, a symbolic and physical threshold between our lives and that of saints, its placement apparently holds the key to that strange film’s multiplicity of contrasting meanings.

Classical paintings such as the Brera Madonna, unlike conventional Hollywood, require active viewers. One cannot sit back and expect to understand everything at a glance. Paintings such as Rembrandt’s The Night Watch, Vermeer’s Girl with a Pearl Earring and Da Vinci’s The Last Supper contain innumerable clues, still puzzling art historians until this day. We must keep looking. Again and again and again.

Greenaway gives us the clues to read his work within his own filmmaking. Nightwatching, a visually ravishing update of The Draughtsman’s Contract, which feels like an epic summation of all Greenaway’s work, gives us a template to try and pick up on his endless behaviours, symbols and gestures. Starring Martin Freeman as the petulant painter Rembrandt, it tells the creation story of The Night Watch, which Greenaway believes hides a murder in plain sight, subverting his prestigious commission for Captain Frans Bannick Cocq’s militia through the use of subtle allegory. Complemented by the documentary Rembrandt’s J’Accuse…! (2008), it implores viewers to become culturally literate, active participants. But much like what happened to the Dutch painter himself, Greenaway’s dense, accusative, morally complex work, has made him a cinematic outsider, especially from the UK, where he has never been praised in the same glowing terms as his social realist contemporaries Mike Leigh and Ken Loach.

Look the other way

Perhaps for an alternate vision into what Greenaway’s career could have looked like, look no further than The Cook, the Thief, his Wife & her Lover (1989; pictured at the top), starring Michael Gambon and Helen Mirren in career-defining roles. While containing many of the same Baroque flourishes littered throughout his work, its clear message of good versus evil, as well savage criticism of 1980s Thatcherite ethics, gave him his first (and last) real crossover success. Taking place almost entirely within Le Hollandais, a Parisian-style London restaurant, the deep, thick, garish reds of the restaurant — owned by Gambon’s monstrous gangster — is contrasted with a large-scale print of Frans Hals’ The Banquet of the Officers of the St George Militia Company in 1616 hung across the wall. A noble schuttersstuk (group militia portrait), it portrays relaxed men, crammed together at a table, all bearing similar facial expressions while being subtly organised by rank. Unlike The Night Watch, this painting is relatively straightforward, used to ironically juxtapose against the horrors unfolding below.

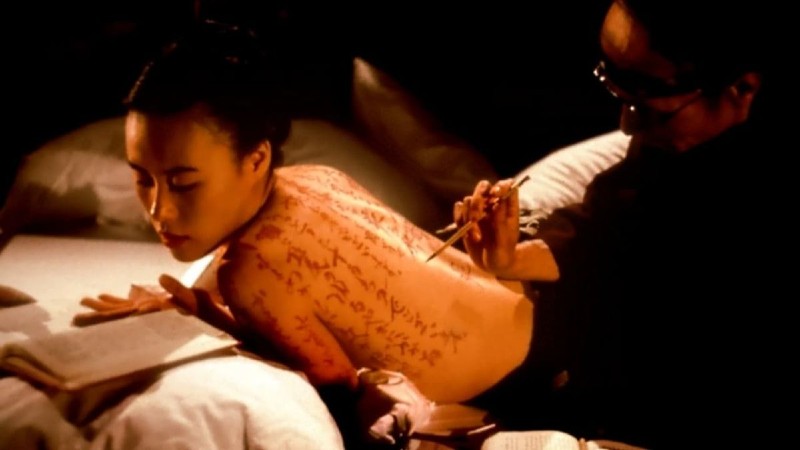

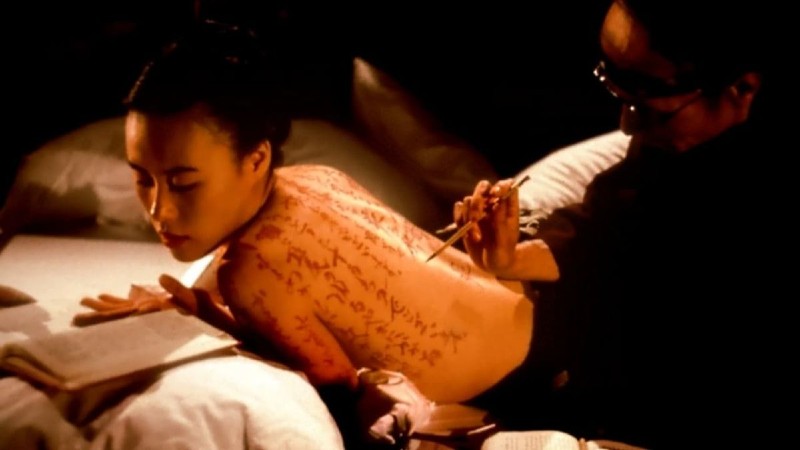

It’s a simple, clear and evocative juxtaposition, one from which meaning can be gleaned straightaway, helping The Cook, the Thief, His Wife & Her Lover — telling a devastating story of infidelity, love, jealousy and revenge — draw its immense emotional power. What to make of the puzzling fact that his best film has the strongest narrative drive, with a clear beginning, middle and end lending it an emotional heart absent from his other works? It was by far his biggest success, and with the goodwill lent to him, perhaps he could’ve bridged the arthouse and the mainstream in a way we see today with Yorgos Lanthimos — who copied many of the mannerisms of The Draughtsman’s Contract with The Favourite (2018). But Greenaway burrowed further into esotericism and obsession, innovating with multi-layered frames in Prospero’s Books (1991) and The Pillow Book (1996; pictured below) before embarking on the dense, multimedia work of The Tulse Luper Suitcases (2003-04), which encompassed an online game, 92 CD-ROMs, four feature films and a 16-episode TV series.

Post The Cook, the Thief, His Wife and Her Lover, his images are not merely connected with story; they overwhelm and consume all sense of narrative. The eponymous library in Prospero’s Books is one place created with remarkable density: a huge renaissance-style recreation caught in an epic opening pan reminiscent of a large-scale painting. And like Prospero’s vast library, Greenaway’s work is best watched (and re-watched) with that cinema-killing remote control close by, in order to pause and reflect upon each densely populated frame.

Beyond the silver screen

Through his lectures and numerous art installations, he postulates ways of imagining film without a frame, wanting to liberate cinema from its so-called “nocturnal environment” and bring it out into another, perhaps more artistically valuable, dimension. Now, with the rise of digital techniques — the sophistication of which is marked quite significantly by the technological improvements between the use of super-imposed images in A TV Dante (1991) and Goltzius and The Pelican Company (2012) — we see the huge potential for cinema to keep on innovating.

Aided by the coronavirus crisis, the dominance of the traditional two-hour feature “symphony” is waning, making creatives across the world search for new forms of expression — from Zoom-only shorts, to screen-life features, to films shot entirely through social media apps. One can see today the ways in which Peter Greenaway’s predictions are slowly coming true. The image is definitely evolving, just not in the painting-influenced way he hoped for.