So you’ve never heard of the 1971 World Cup in Mexico? You never saw the images on the big final with the Azteca stadium packed with 110,000 energetic football fans? You have no idea who Susana Augustesen is? Don’t worry if the answers to all of these questions are “no”. You are not alone. Not even two-time Fifa Women’s World Cup champion Brandi Chastain had ever heard of such tournament, which had been relegated to the dark basement of forgotten history for five decades. The American player is shocked and nearly moved to tears when she sees the images of the boisterous crowds cheering female players long before she dreamt of becoming a footballer (or “soccer player”, in the local vernacular),.

Most people think that the first Women’s World Cup took place in 1991. This enlightening and impeccably assembled documentary reveals that women had an intimate relationship with the most popular sport on earth much earlier, and that they were violently removed from the pitch for shocking reasons. British doc Copa 1971 reveals that there were in excess of 100 female football teams in the United Kingdom in 1917, and it was only in 1921 that they were shut following false medical claims that the sport could hurt their ovaries. The absurd, pseudo-scientific claim travelled far, with Italy and Brazil criminalising women who dared to engage in the activity. The patriarchy sent women back to the kitchen in order to bake cookies for their husbands. It mocked and degraded female footballers. A newspaper wrote: “women playing football are like dogs on their hind legs: clumsy yet fascinating”. Its objective was to permanently dissociate wives, mother, sisters and daughters from the sport, and to keep them away from the spotlight. It succeeded for several decades.

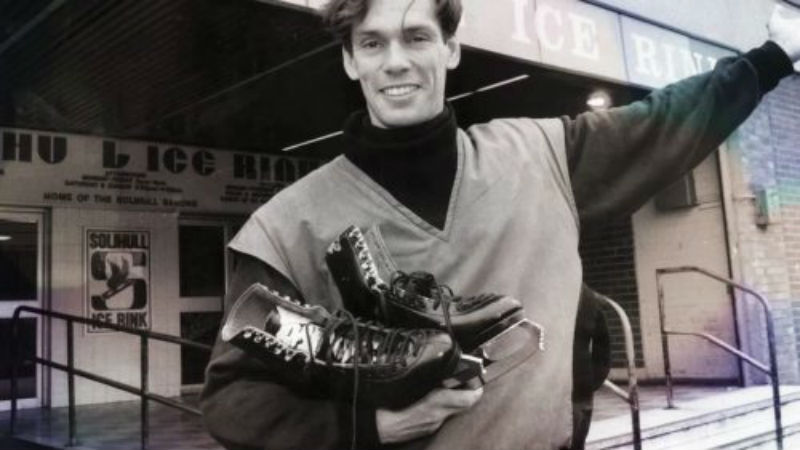

Fifa refused to support or even recognise the Women’s World Cup 1971, which was sponsored by Italian multinational Martini & Rossi (the manufacturers of the eponymous alcoholic beverage). Nevertheless, the event was a massive hit, attracting large crowds to the massive stadiums of Mexico. It seemed for a short period of time that a new passion was being born, and that nothing could stop it. The women were at full throttle. The English team was under the command of Captain Carol Wilson. They were devastated when they lost to Argentina. “We did now anticipate their strength”, one of the players bemoans the defeat (does that ring any bells?). Then they are defeated again to Mexico, thereby failing to qualify for the semi-finals. The hosts were very gracious, visiting the English team in their the hotel in order to offer their warm and heartfelt condolences. Their reception in England was a lot colder. Not a single journalist welcomed the girls at the airport. They hang their heads down in shame and fell into complete oblivion for the next half a century, and never played football again.

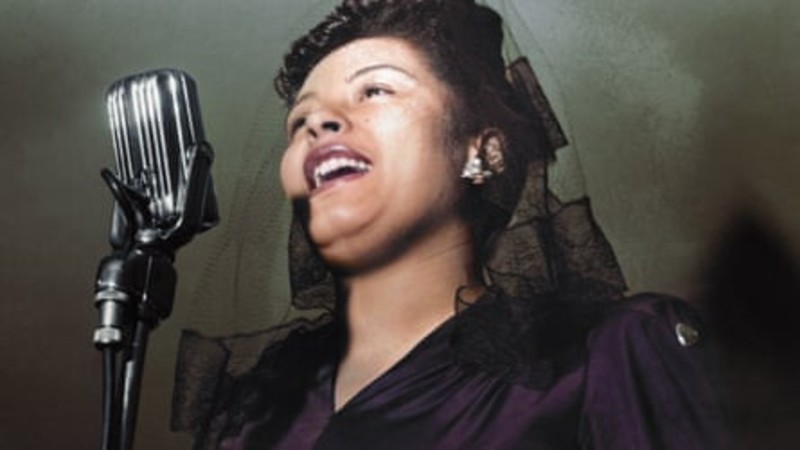

Despite having the best player in the world, a nimble woman called Elena Schiavo, Italy failed to reach the final. The Mexican hosts played against Denmark in the big face off. Susana Augustesen scored three times for the visiting team,. For a few moments, a deafening silence prevailed. But there was still a reason to celebrate, and the match – played at a fully packed Azteca stadium on September 5th – 1971 ended on a very positive note. The six-figure audience is still the largest in the history of women’s sports.

The joy and elation did not last long, however. Fifa, who wanted to have full control of the world of football, were very concerned about the huge commercial potential of the event. So they found a cruel way of stopping these women on their tracks, with a toxic mixture of lobbying and misogynistic practices. Never underestimate the perversity of the patriarchy. Another peculiar revelation is the fact that the Mexican players were never remunerated, despite the event generating an enormous amount of revenue.

This 90-minute documentary is endearing and rapturing from beginning to end. Archive footage is blended with moving talking heads interviews with the English, Mexican, Italian and Danish players, now in their 70s, as they open up their heart. The spark of pride is still visible in their eyes 50 years later. You can’t help but feel guilty for being unaware of the existence of these national heroines. A lively score helps ti sustain the cohesive narrative. This is a story almost too incredible to be believed. At times, it feels almost like you are watching a fiction feature or a mockumentary. The erasing of these women from history is shocking. Congratulations to British filmmaker Rachel Ramsay and James Erskine for doing them a little justice so many decades later. Credit must also go to the United States, the country that helped put women’s football back in the spotlight. Now Brandi Chastain knows she has some early idols upon whom to look. An international and intergenerational message of sorority.

Copa 71 , which was exec produced by Serena and Venus Williams, shows in the 3rd Red Sea International Film Festival, in Saudi Arabua. It premiered earlier this year at IDFA. The significance of this screening being held in a country where just five years ago women could not drive, and which established their first women’s national football team just last year, must not be understated. In cinemas on Friday, March 6th.