Fashion has never moved this fast before. At 24 frames per second, to be more precise.

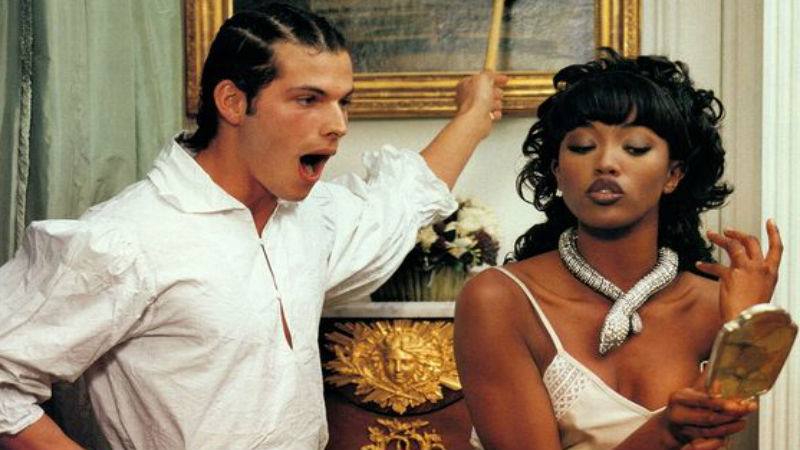

Doesn’t Exist is a publication that merges cinematic elements with a fashion landscape. They become are translated into intricate fashion stories, pictorial written pieces, interviews and filmic illustrations. The objective of the publication is to create a new space to be used by both fashion and film industries, and a mutual feeding of references in all their aesthetic and intellectual fields. The magazine seeks to develop a visual dialogue between the two industries, thereby generating a fully cinematic fashion content.

The first issue is a tribute to the iconic Japanese fashion designer Rei Kawakubo, and the impressive work for the her fashion brand Comme des Garçons. Our writer Redmond Bacon has drawn parallels between the fashion artist and the late Greek filmmaker Theodoros Angelopoulos, arguing that both embrace austerity and reject the mainstream in very assertive and yet different ways.

There is a visual fashion story stylised with archive pieces from Kawakubo’s Paris debut, complementing the words by Redmond. The minimal, groundbreaking collections from the 1980s and 1990s are all there to be savoured.

The first print edition of Doesn’t Exist also features an article about the elusive and mysterious American-born and London based filmmakers the Quay Brothers, and their connection with the fashion world through the means of fragrance. The words were penned by our journalist Jeremy Clarke, and the piece is also embroidered with a set of stylised images, once again straddling between the wondrous world of cinema and clothes.

Two pieces are available exclusively online for readers of DMovies: an article on twisted motherhood, and an interview with the magnificent actress Izabél Zuaa.

The shiny first edition of Doesn’t Exist has 244 pages, and it is available to purchase in four different front covers from various stockists across the UK, Portugal and Italy, both on the high street (once the lockdown is over) and online. You can see the full list by clicking here, or by visiting their Instagram.

In order to celebrate the partnership between DMovies and Doesn’t Exist, and the enduring connection between the movie and the fashion worlds, we are giving away five copies of the magazine entirely for free posted to you. Just send us an email to info@dirtymovies.org, and let us know the title of your favourite movie by Theodoros Angelopoulos. The promotion is valid for readers anywhere in the world!

All images in this piece are taken from the first print edition of Doesn’t Exist. Find out more on their website by clicking here.