Both a great primer on the man behind the look of the ‘70s and a dazzlingly enjoyable documentary in its own right, the Frédéric Tcheng (Dior and I, 2015) movie is perfect for both in-the-know fashion enthusiasts and those who know nothing about fashion at all.

Born Roy Halston Frowick, Halston’s designs and influence upon American fashion are undeniable. His fame started with his groundbreaking work as a milliner for Bergdorf Goodman (including that pillbox hat Jackie Kennedy wore at her husband’s inauguration) to finally establishing his own company by the end of the decade. He ushered in the classic ‘70s look, with simple, uncluttered garments elegantly constructed from single pieces of fabric. At the same time, he was chummy with Andy Warhol, organising happenings that were the talk of New York cafe society, a regular at Studio 54, took American fashion to China, and presented American style to the French fashion world with a Liza Minelli-starring mini-musical at the palace of Versailles. Wherever the ‘70s was, he was there.

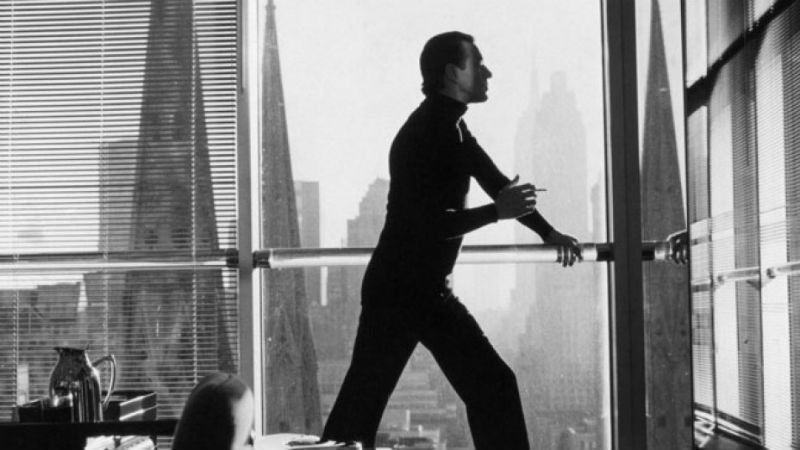

Everything was about branding. He always travelled with a group of impossibly beautiful models, known as the “Halstonnettes”. He changed the pronunciation of his moniker from “Halsten” to “Holston”. Even his worker’s had a uniform — strong, blocky, black costumes — so they wouldn’t detract from the clothes itself. Things that other people wouldn’t think of, Halston spent hours poring over, making sure that they were absolutely perfect, streamlined down to their essence. In many ways he predated the sleek designs of modern retail products, for example the iPhone, by elegantly displaying how less can be so much more.

This is a rise and fall story, however, Halston eventually showing the limits of his vision in the face of the rapid commerce of the 1980s. Like many businesses, the number one difficulty in maintaining a successful fashion empire is scalability. Moving from a small boutique store to working with the top retailers in female fashion is a gargantuan task, as affordability and mass production must be balanced with impeccable style. Halston demanded that every product had to go through him first; a conflict that comes to a narrative head while working for mass retailer JCPenney. Soon the control-freak artist finds himself being shut out of his own company to devastating results.

The documentary tackles his energetic and often larger-than-life story with a lot of style, creating a strong aesthetic to match Halston’s style. It’s metafictional techniques – such as the replay of archival footage on vintage TV screens, or the use of a “fictional” narrator who offers her own elaborations on Halston’s life – compliments the way Halston would present himself and his products on the world stage. While many of the traditional documentary techniques are here – including talking heads and old interviews – director Frédéric Tcheng finds a variety of ways to complicate the narrative, allowing the viewer to find their own personal connection to Halston’s work.

This approach seeps into the narrative too, only finally tackling his humble youth growing up in Des Moines, Iowa by the very end of the film. By starting with the legend first before revealing the man behind the curtain, Halston creates a smart treatise on how success is often predicated upon never showing your true self, and the true, tragic cost of acting in such a manner. Therefore it moves beyond the realm of the specific (Halston’s life) to the universal (success and artistry in general), posing the ultimate question to any young budding entrepreneur, be that in fashion or any other industry: how can you succeed without losing yourself at the same time?

Halston is out in cinemas across the UK on Friday, June 7th.