January can be a cold and lonely month. It’s the perfect time to get your teeth into those Christmas box sets and catch-up on some under-the-duvet film streaming. Of course, the first month of the new year also marks another film-related event: the Academy Award nominations. Love them or loathe them, the Oscars can’t be ignored by any self-respecting cinephile. If you take the chilly trip outside to your local small screen or multiplex, you’ll be met with a deluge of films that are expertly-acted, tightly-produced and exquisitely-shot.

Nonetheless, the Oscars are a divisive event. For some, the feeling persists that they are a longstanding form of American cultural imperialism, a supposed bellwether for the wonders of the big screen, in spite of their frequent dismissal of smaller independent-minded productions and international cinema. In recent years, the Academy have also faced accusations of racial bias, largely kickstarted by actor April Reign’s #OscarsSoWhite campaign. In addition, Ronan Farrow’s 2017 exposé has blown the lid on Harvey Weinstein’s long-rumoured criminal misogyny, as well as broader accusations of Hollywood’s ingrained culture of sexual harassment, assault and rape. As a result, the Academy have found themselves under increasing pressure to showcase the talents of women, people of colour and other individuals (e.g. LGBTQ and Latins) who are prominent on our screens, yet underrepresented among Oscar nominations.

The above biases may in part result from an Academy membership that is still largely white and male. Women now constitute 28% of its voters, while just 13% of its membership are people of colour. This historic issue has also contributed to a phenomenon known as Oscar bait. Oscar bait refers to a certain kind of film that seems to get showered with awards year-after-year and therefore encourages an industry to put out bland productions that are voter-friendly. Oscar bait films are often period pieces, biopics or tributes to the Hollywood industry. They might revolve around an historic tragedy, such as the Holocaust or another brutal chapter from the Second World War. Their narrative arcs can be predictably saccharine, involving banal character transformations that are bound to invoke audience emotions. And they might cynically cast actors with high nomination rates, individuals like Daniel Day-Lewis and Meryl Streep.

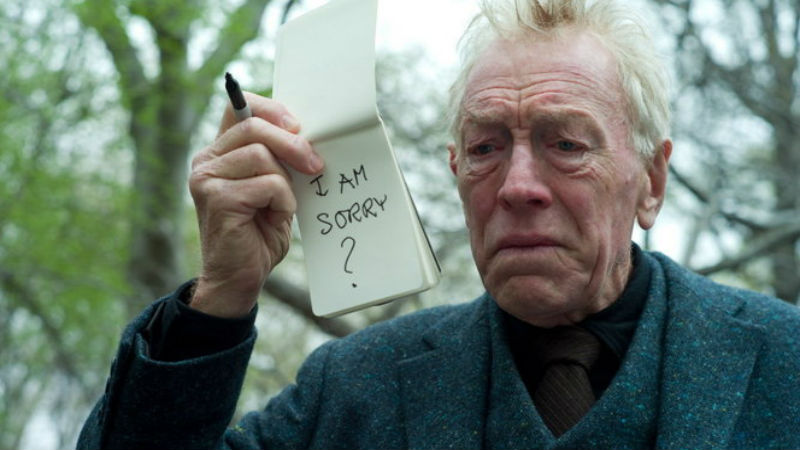

The act of baiting naturally implies that you are aiming to kill something, as in the food placed on a hook or in a net in order to catch a prey. In the case of the Oscars, this can present itself in deadweight scripts, side-lined supporting performances and the grave of historical accuracy. However, it’s not necessarily the case that all Oscar bait films are objectionably awful. There will always be a schmaltzy Extremely Loud & Incredibly Close (Stephen Daldry, 2011; pictured ), a Tom Hanks 9/11 emotion-fest that focuses on a child with Asperger’s syndrome. We’re equally blessed with the likes of Birdman (Alejandro González Iñárritu, 2014), which may bait with its acting industry setting and reborn Hollywood star protagonist, yet excels in cinematography.

Here are five examples Oscar baiting has “killed off” other elements of the film:

.

1. Darkest Hour (Joe Wright, 2017) – kills off historicity:

The Oscars absolutely love an historical biopic. Unfortunately, this also means that Oscar bait films tend to have a murky relationship with the truth. You see, if real events aren’t quite compelling enough and you really really want that Oscar, it’s definitely worth deceiving your audience, right? Of course, it’s entirely reasonable for feature films to use some creative license. After all, they’re pieces of fictional work rather than documentaries. The issue is most pertinent when a biopic purports to be the whole truth and nothing but the truth. Darkest Hour is the latest offender in this category. From its bold advertising campaign that declares: “Gary Oldman is Winston Churchill”, to its use of brash full-screen dates for each new scene, everything about it screams this is factual.

However, when it comes to the facts of what actually went down in May 1940, the film is surprisingly lacking. The most offensive scene by far is a bizarrely concocted sequence on the London underground. In a flash of fictional nonsense, Churchill travels on public transport and speaks to an assortment of ordinary Londoners, in spite of his well-documented classism and racism. To add insult to injury, director Joe Wright ignores the time constraints of travelling a single stop on the underground. This means that he can use as long as he wants to get exactly what he needs from this entirely invented scene – namely, a situation in which Churchill gains popular public support for his famously rousing ‘fight them on the beaches’ speech.

It’s classic bait and Gary Oldman will compel many an Academy voter with his virtuous closing oratory. It’s just a shame that historicity has been murdered along the way.

.

2. Manchester by the Sea (dir. Kenneth Lonergan, 2016) – kills off multi-layered characters:

If you’re not sure how to get your Oscar, you can always latch onto the ageing Academy elite’s desire to appear woke and relevant. Manchester by the Sea achieves this by presenting itself as a dissection of the flavour of the year, toxic masculinity. On the surface, it appears to do this through placing its Casey Affleck bait on a big emotional plate. The protagonist alpha-male janitor has committed an awful act in the not-so-distant past that he is forced to face again when his brother dies and leaves a son in need of a caregiver. We have an aggressively masculine man. We have said man being placed in an atypical caring role. We have plenty of potential for this man to erupt into tears and take the audience on his pathos-driven journey. So far, so good.

Unfortunately, through focusing so deeply on its protagonist’s supposed emotional heroism, the film kills any chances of properly deconstructing what might give rise to his toxic masculinity. In fact, it goes some way to firing up gender stereotypes by giving women entirely one-dimensional characters. Fancy being an alcoholic, hysteric or sexual plaything? Probably not, but that’s your lot as a woman in this film.

Manchester by the Sea also displays the Academy’s utter hypocrisy and conservative judgement of character. In 2010, Casey Affleck faced sexual harassment allegations that he settled out-of-court and which were subsequently kept quiet by his Oscar campaign team. On the other hand, Nate Parker, the director of one-time Oscar hopeful Birth of a Nation (2016), had historically been found not guilty of sexual assault, a case that was repeatedly brought up by media. Affleck’s alleged dark past was kept under wraps, while Parker’s was out for all to see.

Affleck won his Oscar, while Parker’s hopes of a nomination faded away. In the eyes of the Academy membership, it’s fine to behave badly, as long as you keep it hidden. Even better, if you can bait them with some lip service to the issue of the day, the Academy will forgive, forget and reward.

.

3. La La Land (dir. Damian Chazelle, 2016) – kills off self-criticism:

In a fleet-footed rush of sunshine vibes and happy endings, La La Land tap-danced across our screens in late-2016, shuffling and twisting its way through numerous awards. Seven Golden Globe nominations, seven record-breaking Golden Globe wins. An impressive 11 Bafta nominations, followed by a solid haul of five Bafta wins. And, of course, those record-tying 14 Oscar nominations, with a not-too-shabby six Oscar wins. In fact, the Academy loved the film so much that they almost awarded it Best Picture in place of the more deserving Moonlight (dir. Barry Jenkins, 2016), in a classy Oscar gaffe.

La La Land had serious appeal on both sides of the Atlantic. Plus, its performance in the Academy Awards was pretty remarkable for a film made on a $30m budget. Titanic (dir. James Cameron, 1997) may have the joint-most Oscar nominations and wins, but it also had $200m behind it – approximately ten times Damian Chazelle’s budget, if we account for inflation. So how did La La Land manage the masterstroke of widespread Academy Awards success on limited funds? Quite simply, through throwing out the classic Oscar bait of self-referencing the Hollywood film industry in all its dream-fulfilling glory.

From start to finish, the film has no qualms about projecting its loud love of Hollywood, thereby killing off any possibility of self-criticism. It sets the scene with old-school Hollywood title cards. Next, the proud declaration that it’s “Presented in CinemaScope”, a tribute to the mid-20th century musicals that the film riffs on (although notably, it wasn’t actually shot using CinemaScope lenses – it was shot in the same 2.55 aspect ratio). The film is then littered with Casablanca (dir. Michael Curtiz, 1942) references, classic musical numbers and a treacly narrative of the City of Dreams coming good on its promise. In case the previous two hours weren’t clear enough, the film ends with the statement “Made in Hollywood, USA”. In summary, La La Land reminded the Academy voters of how they want their industry to be perceived, even if the reality is about as real as two tap-dancing romantics literally floating through the Griffith Observatory.

There’s a reason that the likes of Barton Fink (dir. Joel Cohen, 1991), Adaptation (dir. Spike Jonze, 2002) and Mulholland Drive (dir. David Lynch, 2001) don’t make the Academy membership ecstatic. A little bit of back-slapping can go a long way.

.

4. Arrival (dir. Denis Villeneuve, 2016) – kills off balanced representation:

British auteur Christopher Nolan is known for making big-budget ‘intelligent’ sci-fi with a twist (Inception, 2010; Interstellar, 2014). In recent years, Quebecois director Denis Villeneuve has also ventured into the English-language sci-fi arena. His first major effort, Arrival, certainly teased the Academy into a number of nominations and a Best Sound Editing win. At first glance, it might not appear to be typical Oscar bait. Yet beneath the surface it represents a growing trend: that of the smart sci-fi flick.

The Academy are traditionally loathe to reward genre films, meaning that science fiction has generally been underrepresented at the Oscars, despite its clear merits. Since the 2009 expansion of Best Picture nominees from five to nine, sci-fi has crept onto the nomination lists. Considered and leftfield pieces of filmmaking, such as District 9 (Neill Blomkamp, 2009) and Her (Spike Jonze, 2013) have been nominated without any ultimate success. On the other hand, Arrival generated considerable buzz. Why might this be? While District 9 works as an apartheid allegory for racial oppression and Her delivers a depressing verdict on an increasingly disconnected society, Arrival throws in some good old-fashioned Manichaean stereotyping of other superpowers (in this case, the Russia and China) in order to broaden the appeal of its (mostly) clever story.

The plot of Arrival revolves around 12 extra-terrestrial vessels that land in Australia, the Black Sea, China, Greenland, Japan, Pakistan, Siberia, Sierra-Leone, Sudan, the UK, Venezuela and, the setting of the film, the US. Large parts of the film are dedicated to diplomatic communications between these countries, during which cultural stereotypes abound. The Brits say “you cheeky bastard”, the Sudanese wear shemagh while running around and praying, and the Russians are military aggressors who immediately cut off multilateral negotiations. Interestingly, inter-country conflict is not described in the film’s source text, Ted Chiang’s novella Story of your Life. This suggests that there was a specific reason for its inclusion. This reason becomes clear in the final act where China threatens world peace with their final spaceship solution, but are ultimately won over by an American nonviolent intervention.

History tends to suggest that the US has a violent history of military interventions. We don’t know what Villeneuve’s political beliefs are and he’s entitled to keep them close to his chest. Regardless, it’s no surprise that a sci-fi film in which the Russians and Chinese are the baddies and the Americans peacefully save the day played so well with an Academy membership that is largely old, white and male.

.

5. The Revenant (dir. Alejandro González Iñárritu, 2015) – kills off other artistic achievements:

Alejandro González Iñárritu’s back-to-back Best Director wins for Birdman and The Revenant are impressive enough, until you realise that his Director of Photography, Emmanuel Lubezki, won his third consecutive Best Cinematography award for this 2015 violent revenge epic. Lubezki shot the entire film using natural light and this is reflected in the breathtakingly gorgeous landscapes that intersperse the narrative. The film also opens with a beautifully choreographed action sequence. Clever camera trickery gives the impression of a single take, as mounted native Arikara warriors attack the group of European fur trappers. And let’s not forget Ryuichi Sakamoto’s subtly savage score.

On a technical level, the film is fantastic. However, all of these achievements have been overshadowed by one single man. The movie will be forever remembered as the one that finally bagged Leonardo DiCaprio his long-awaited Oscar for Best Actor. How exactly did the film achieve this? Quite simply, through an admirably concerted Oscar bait campaign. In the build-up to its December 2015 release, DiCaprio was on top form describing the sheer extremity of his filming experience. From crossing frozen rivers to sleeping in an animal carcass and trekking up hills carrying sodden bear fur, the actor spared no details about his “journey down the heart of darkness.” Even the narrative of The Revenant works as a metaphor for its star’s statuette ambitions. It’s the story of a man who is left behind on multiple occasions, suffers numerous injustices and puts himself through a gruelling regime to claim his late victory.

Ultimately, these efforts paid off. Don’t get me wrong, DiCaprio is absolutely deserving of an Oscar, perhaps more so for his show-stopping performance in The Wolf of Wall Street (dir. Martin Scorsese, 2013). The whole affair is simply a lesson in how to tug on the Academy’s heartstrings and bait them into righting a supposed wrong.