Sex is subversive by nature. It must not be regimented and sanitised. “Excuse me, madam, may I please insert my penis is your vagina, but only if it’s not too much trouble, of course” isn’t the sexiest introduction to intercourse. Seduction and flirting often preclude words. Consent can be negotiated in many ways, not necessarily with onerous and unambiguous words. The nuances of sexual attraction often rely on ambiguity. Yet the Swedish seem to disagree. They plan to pass a new law requiring “explicit” and “clearly-worded consent before sexual contact.

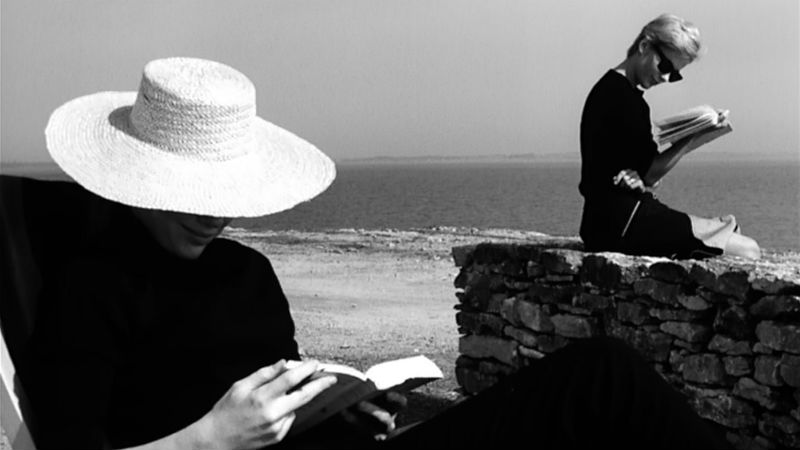

This is part of a much broader movement against the rape culture, which is pervasive in many societies and cultures, and the movie industry is no exception. Harvey Weinstein and many others are a testament that women have been consistently abused, and their horrific predicament has been dismissed as futile for too long. But then came the backlash. From women even. Yesterday Catherine Deneuve (pictured below in Bunuel’s 1967 classic Belle de Jour), Catherine Millet and 98 other French female artists stoked fire into the discussion by publishing an open letter defending a man’s right to “hit on women”.

I’m a gay man, and – while of course I agree that the rape culture must not be tolerated – I’m also in agreement with Deneuve and Millet. We must choose our weapons more carefully. There is a lingering puritanism and sexphobia in some of the arguments proposed by the #MeToo movement. We must be careful not to radicalise the movement, therefore opening another can of worms. A woman in the US has recently claimed harassment after a man said “hello”. Plus the anti-rape rhetoric is being used for very questionable political purposes. In Germany, Austria and Scandinavia, the far-right is using rape allegations in order to stigmatise Syrian refugees. Norway is providing compulsory anti-rape courses to male and Muslim refugees. This fuels misandrism, Islamophobia and xenophobia. Three ugly birds out of the cage, all at once.

This is why I would like to take the opportunity to celebrate our freedom to flirt and to have sex. We must not monitor and regulate seduction. Ultimately, if Sweden does approve the law requiring “clearly-worded” consent, the sex that Alma (Bibi Andersson) describes in Ingmar Bergman’s Persona (1966) – in what’s often described as “the most erotic scene in the history of cinema” – could be made illegal. Read it yourself below and reach your own conclusion. Nothing in it is clearly-worded. The women barely speak and the men never open their mouths. And that’s how sex and seduction in cinema should remain: dirty, nuanced and enigmatic.

…

.

“I went to the beach on my own. It was a warm and nice day.There was another girl there. She had come from another island because our beach was sunnier and more secluded. We lay there completely naked and sunbathed… dozing off and on, putting sunscreen on. We had silly straw hats on. Mine had a blue ribbon. I lay there… looking out at the landscape, at the sea and the sun. It was kind of funny.

Suddenly I saw two figures on the rocks above us. They hid and peeped out occasionally. “Two boys are looking at us,” I said to the girl. Her name was Katarina. “Let them look,” she said, and turned over on her back. I had a funny feeling. I wanted to jump up and put my suit on, but I just lay there on my stomach with my bottom in the air, unembarrassed, totally calm. And Katarina was next to me with her breasts and big thighs. She was just giggling. I noticed that the boys were coming closer. They just stood there looking at us. I noticed they were very young.

The boldest one approached us… and squatted down next to Katarina. He pretended to be busy picking his toes. I felt very strange. Suddenly Katarina said to him, “Hey, you, why don’t you come over here?” Then she took his hand and helped him take off his jeans and shirt. Suddenly he was on top of her. She guided him in and held his butt. The other boy just sat and watched. I heard Katarina whisper in the boy’s ear and laugh. His face was right next to mine. It was red and swollen. Suddenly I turned and said, “Aren’t you coming to me, too?” And Katarina said, “Go to her now.” He pulled out of her and… then fell on top of me, completely hard. He grabbed my breast. It hurt so much!

I was overwhelmed and came almost immediately. Can you believe it? I wanted to tell him to be careful not to make me pregnant… when he came. I felt something I’d never felt in my life… how his sperm was shooting inside me. He held my shoulders and bent backwards. I came over and over. Katarina lay there watching and held him from behind.

After he came, she took him in her arms and used his hand to make herself come. When she came, she screamed like a banshee. The three of us started laughing. We called to the other boy, who was sitting on the slope. His name was Peter. He seemed confused and was shivering there in the sunshine. Katarina unbuttoned his pants and started to play with him. And when he came, she took him in her mouth. He bent down and kissed her back. She turned around, took his head in both hands, and gave him her breast. The other boy got so excited that he and I started all over again. It was just as nice as before. Then we had a swim and went our separate ways.”

*All the images on this article are from Bibi Andersson in Persona, except for Catherine Deneuve in Belle de Jour.