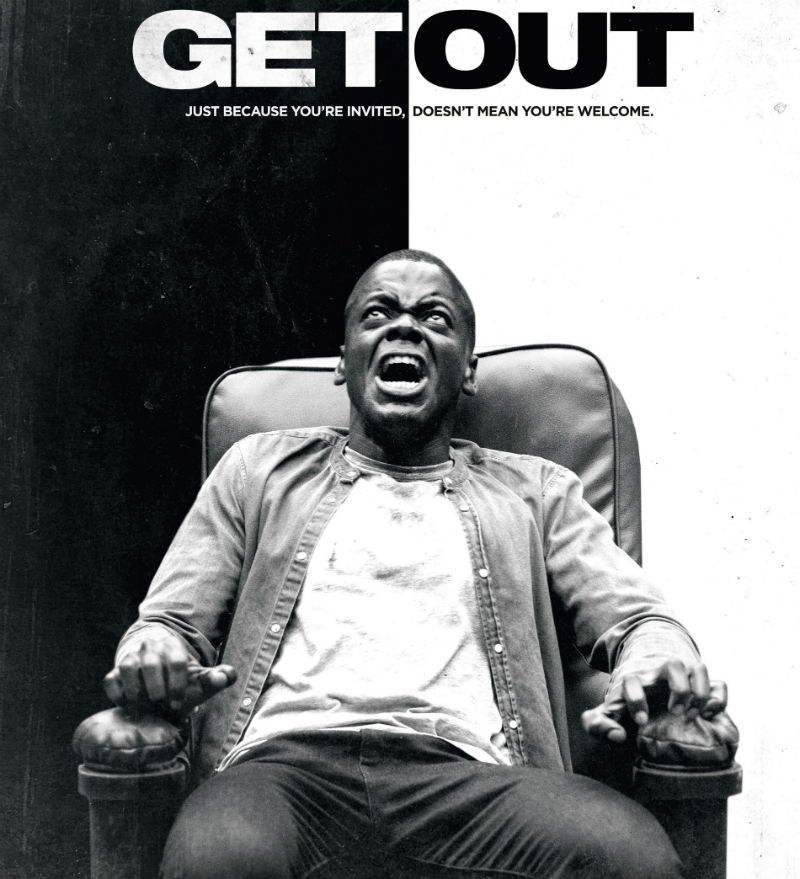

First things first: this Hollywood movie has an amazing trailer and a very powerful black and white poster image. It would be nice to think that cinemas fill up for films that are of themselves excellent, perhaps because they get great reviews, but trailer and poster probably account for more bums on seats. Sadly.

You can probably see where this is going. Get Out isn’t a bad film. But it’s nowhere near as good as the trailer. Basically, if you’ve seen the trailer, you’ve more or less seen the film.

The real problem is that it’s got a really great underlying and, as luck would have it, timely idea which would probably have made an astonishing 35 minute short. But it’s been padded out to feature length by falling back on horror movie clichés and homages. It seems that ‘homage’ is an intellectual word for ‘rip-off’.

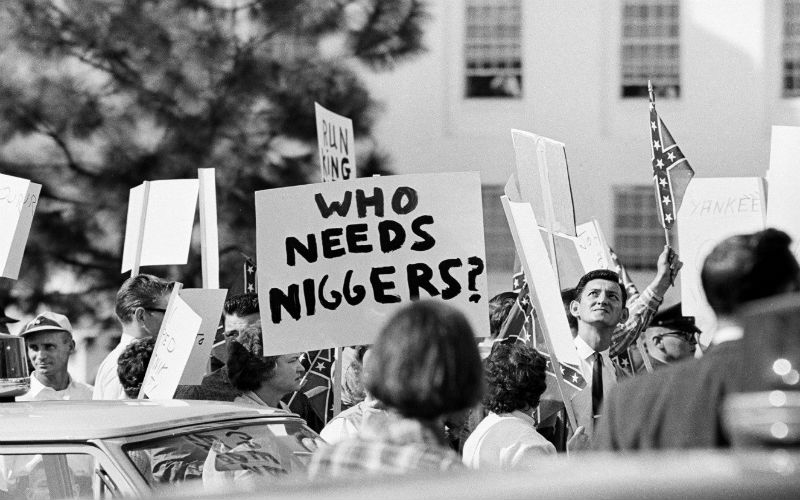

So, the great and timely idea. She’s white, he’s black, they go out to meet her parents and find a pleasant white couple with black servants. The black servants appear to under some sort of mind control to make them more palatable to white people. That’s all in the trailer along with a few other, nightmarish bits and pieces.

Oh, and the weekend they’ve picked is the one where annually all the parents’ friends gather at the family residence for a get together. So far, so good. And given that white America has just elected Trump as its president, very timely.

There is more here that’s good, actually. It’s a very good cast, particularly British-born Daniel Kaluuya as the male lead and veteran actress Catherine Keener as the mother. The mother’s role is one of the better things in the script, a very clever portrait of a hypnotist plus some smart filmic sleight of hand and Keener rises brilliantly to the challenge. The film’s other ace is the lead’s best mate played by LilRel Howery, who seems to have wandered in from a comedy and whose scenes light up the film whenever he appears. Indeed, although promoted as a horror film, it’s a moot point as to what Get Out actually is. A horror film? A comedy? A horror comedy? Maybe one shouldn’t try to pin it down to a genre.

There is an extraordinary and beautifully handled moment early on the when the young couple’s car hits a deer on the way to her parents’ house.

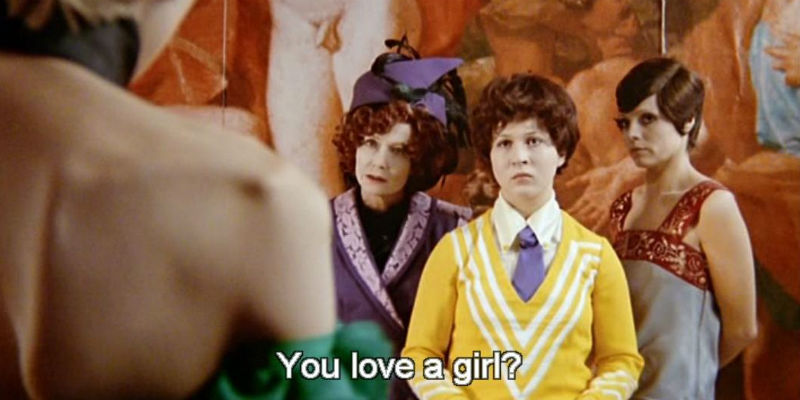

Where Get Out falls apart, though, is in its pilfering of ideas and tropes from other sources whilst hoping that no one will notice. Sadly, we’ve seen The Stepford Wives (Bryan Forbes, 1975) so to rework that as The Stepford Blacks smacks of plagiarism. As the plot progresses, you start to notice other borrowings – a man sinking in to black darkness from Under The Skin (Jonathan Glazer, 2014), a man bound to a chair and watching a TV out of Videodrome (David Cronenberg, 1983) a surgeon’s home operating theatre taken from French classic Eyes Without A Face (Georges Franju, 1960). And a particularly silly sequence towards the end has one character attack or kill several others in an attempt to escape which has appeared in countless horror films.

That said, there are still some clever moments, such as the plot’s resolution for which producer-writer-director Peele pulls an unexpectedly neat trick out of his bag. Overall, though, this writer was disappointed. Peele is clearly a talent to watch, but first time out he doesn’t quite cut it. Mind you, the trailer and the poster deserve Oscars.

Get Out was out in UK cinemas in March, when this piece was originally written. It is out on DVD, Blu-ray and all good DoD platforms on July 24th.