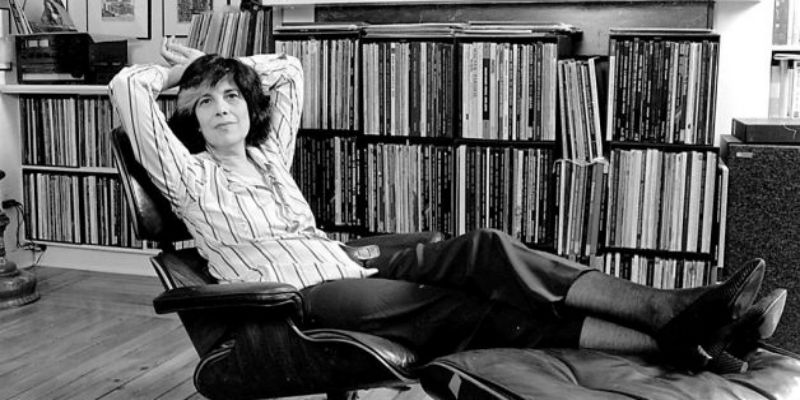

The word “Camp” is often bandied around, a label slapped on anything over-the-top or “so bad it’s good”, but its definition is singularly difficult to pin down. Susan Sontag’s landmark essay Notes on Camp is perhaps the most successful and most famous attempt at defining Camp. She claims that its essence is “love of the unnatural: of artifice and exaggeration.” Camp is marginal; Camp is failure; Camp is “off”; Camp is theatrical, but it is also sincere, undiluted by irony. Sontag eschews deliberate Camp as less satisfying. However, this is not the universal position. DMovies’ own Lobo Pasolini points out that it has long been used purposefully by members of the LGBTQ+ community as a form of not only celebration but resistance. Camp is ineffable, but it exists everywhere. It exists in clothes, décor, people, and, of course, film. Whether via a facial expression or a single line delivery, the 10 films below embody the Camp sensibility.

The movies below are listed in chronological order.

…

.

1. Sunset Boulevard (Billy Wilder, 1950):

Long considered a Camp classic, Sunset Boulevard’s appeal lies in the mesmerisingly over the top performance of Gloria Swanson as the ageing movie star, Norma Desmond. The character’s every action is itself a performance. She speaks and moves with gravitas, living her life as though onstage. Swanson’s performance fully encapsulates the theatricality of Camp. But there is more to Sunset Boulevard’s Camp appeal than just this. It also lies in Norma’s disconnect with the modern world. She no longer fits in the Hollywood of the 1950s; despite all her grandeur, Norma Desmond is “off”.

Sunset Boulevard is also pictured at the top of this article.

.

2. Johnny Guitar (Nicholas Ray, 1954):

This film turns the hypermasculine Western genre on its head, focusing instead on a face-off between two powerful, larger-than-life women. Vienna is a saloon proprietor with a penchant for masculine clothing and a longing for independence, while her arch-enemy Emma is a bank owner with the townspeople under her thumb and a psychosexual obsession with Vienna. Gender and genre are entirely at odds in Johnny Guitar, making it a failure in some ways but a fascinating one, and therefore a Camp one. The behind-the-scenes feuding of Joan Crawford and Mercedes McCambridge further reinforces the Campiness of the film by transforming real enmity into a cartoon of itself.

.

3. Viva Las Vegas (George Sidney, 1964):

Ann Margret and Elvis are fundamentally mismatched in this 1960s oddity. His lacklustre performance and wooden expressions would have made certain that Viva Las Vegas was quickly forgotten were it not for Ann Margret’s impossibly vivacious energy. She doesn’t dance so much as bounce off the walls, bringing 110% to every single moment she’s on camera. She’s a delight to watch, but it’s the juxtaposition between the two performances that makes this film a Camp treat. Her exaggerated movements alongside his nothingness highlight the artificiality of this strange attempt at a movie-musical star vehicle.

.

4. Valley of the Dolls (Mark Robon, 1967):

Charting the rise of fall of three young pill-addicted starlets, Valley of the Dolls was an underwhelming adaptation of Jacqueline Susann’s novel of the same name. Camp connoisseurs, however, were quickly drawn to its tacky aesthetics and to Patty Duke’s unforgettable histrionics as Neely O’Hara. In the final scene, she sinks to the ground in her fur coat and big 1960s’ hair, screaming out her own name to God and banging her fists on the ground in a veritable feast of overacting. More than anything though, it is the earnestness with which Valley of the Dolls tells its tragic tale of stardom that makes it an enduring Camp classic.

.

5. Pink Flamingos (John Waters, 1972):

This notorious John Waters film is pure bad taste. It includes everything from cannibalism to foot fetishism, and it lampoons conservative sensibilities. Rather than simply being a shocking film or a good satire, however, it is Camp. The performances are melodramatic yet stilted, the dialogue is strange and awkward, and the soundtrack is inappropriately twee (Patti Page’s How Much is that Doggie in the Window?). This Camp quality comes most of all from the combination of poor taste and fierce celebratory nature. Pink Flamingos is an act of queer resistance that exaggerates and deconstructs gender, sexuality, and a whole host of other things.

.

6. Man of La Mancha (Arthur Hiller, 1972):

This musical adaptation of Don Quixote reaches for the soaring heights of its Golden Age. It attempts to be profound, stirring, melodramatic, and in all of this it falls woefully short. Man of La Mancha is stuck in another decade, a failed bid at a great movie musical in an era that was already done with the genre. However, its most spectacular failure is in the casting of Sophia Loren, whose sympathetic portrayal of the sex worker Aldonza is hilariously undercut by her tuneless, off-key “singing”. Failure on such a grand scale cannot be considered anything but Camp.

.

7. The Rocky Horror Picture Show (Jim Sharman, 1975):

Rocky Horror is intentional Camp, and contrary to Sontag’s assertion it is endlessly satisfying. While its campiness is often praised for the sense of fun it brings to the viewing experience, it is also integral to the themes of the film. The characters of the film find self-acceptance and liberation through the b-movies of yesteryear and the gender expression of their stars. Camp is how Dr. Frank-N-Furter relates to the world and to people. Nowhere is this more evident than in Frank’s final number, I’m Going Home, which uses the artifice of spotlights, costumes, and makeup to convey something heartbreaking and very real. Camp is the emotional core of Rocky Horror.

8. Mommie Dearest (Frank Perry, 1982):

This take on Joan Crawford’s abusive relationship with her daughter was perhaps always destined to be a Camp classic, given that Joan Crawford herself has long been associated with the label, but Faye Dunaway’s portrayal of the star cements it. Her thick painted eyebrows and her unhinged ranting are nothing short of iconic, and her performance also hits on the empowering quality of Camp. As funny as the famous “don’t fuck with me fellas, this ain’t my first time at the rodeo” line is, there is also something cathartic about seeing this confident, strange, hurt woman face down a room full of patriarchal businessmen. Even at its most ridiculous, Mommie Dearest embodies the sincerity of Camp.

.

9. Barbie as the Princess and the Pauper (William Lau, 2004):

This seemingly forgettable straight-to-dvd Barbie movie has developed a cult following in recent years, and it’s not hard to see why. Every element of Princess and the Pauper is Camp, from sheer ridiculousness of the queer-coded animal sidekick Wolfie, a cat that barks, to the crown-shaped royal birthmark that distinguishes the ‘princess’ from the ‘pauper’. However, by far the most Camp part of the film is its villain, Preminger. His villainy is so exaggerated that he appears as almost a caricature of the evil advisor trope, maniacally laughing his way through the film and making bizarre noises at every opportunity. Princess and the Pauper turns the conventional princess movie on its head, revelling in the strangeness of its side-characters and making us pay more attention to the villain than the hero. \

.

10. Jupiter Ascending (Lana and Lilly Wachowski, 2015):

Intended as an intergalactic tale of family, love, and political manoeuvring, Jupiter Ascending is definitely one of the weirder sci-fi offerings of the last decade. Its operatic scale clashes fantastically with its clunky script, leading to insane snippets of dialogue, such the protagonist flirting with her half-canine companion by saying “I like dogs”. As in Princess and the Pauper, the most concentrated Camp in Jupiter Ascending comes in the form of the villain, Eddie Redmayne’s emperor Balem. Decked out in Bob Mackie-esque designs and oscillating between dramatic screams and hoarse whispers, this character is operating on a level of Camp that even the rest of the film couldn’t dream of.