The Encounters Film Festival taking place in Bristol from September 20th to 25th is now firmly established as one of the UK’S leading film festival in the areas of short film and animation. With more than 2200 short films submitted and more than 400 selected each year, Encounters screens some of the best British and international contemporary talent, giving the opportunity to new and emerging voices to be heard. Its diverse programme reflects expressions of creativity, imagination and experimentation, exploring the possibilities of the medium and questioning traditional modes of filmmaking.

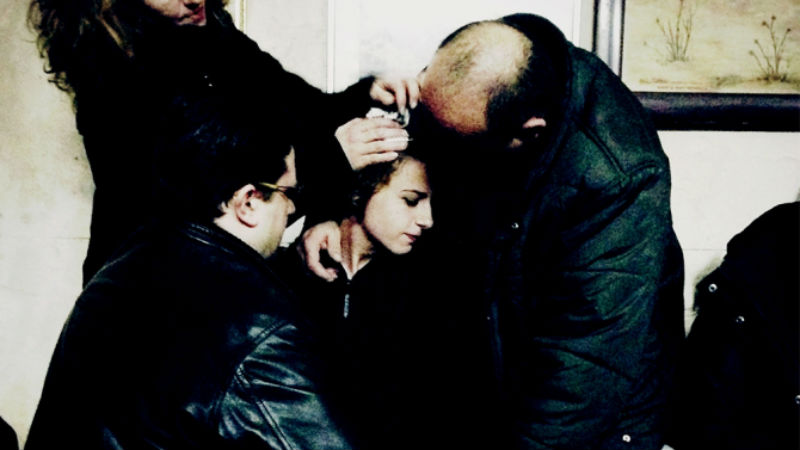

The event has a long tradition of investigating and presenting new cinema waves and innovative filmmakers. Last year’s focus on Romania included a thorough exploration of the Romanian New Wave with a series of screenings of Romanian shorts and masterclasses by the acclaimed director Adrian Sitaru and the talented actor Adrian Titieni. Along with the new emerging talent, Encounters hosted a number of already established artists, such as the Swiss director and screenwriter Ursula Meier and the experimental British filmmaker Carol Morley.

.

.

The lowdown this year

This year’s programme is very audaciouys and and inspiring, with the new strand ‘Widening the Lens’ exploring alternative viewpoints and examining matters of disability, gender, LGBT and non-white representation on screen. A series of short films will challenge our perception of ‘normal’ thereby foregrounding diversity and differentiation. Panel discussions, such as ‘Grrls on Film’ and ‘The Ethical Approach to Diversity’ will open up the debate on the representation of the female figure on screen and ways to promote diversity and inclusion.

In a period of significant politico-economical upheavals and redefinition of national borders, Encounters reflects the human anguish and pain with a series of short films that explore the act of migration and the brutalities faced by refugees.

Bloody Foreigners is a mixture of six thought-provoking international short films that examine the refugee crisis on the European borders, the often hostile circumstances and the racist atmosphere in the host countries, the reactions of the native populations and the despair and anxiety of the refugees in their difficult ‘journey’ to flee their country and establish a new life in a new land. Similarly, Ode to Lesvos presents the stories of the people of the Greek island Lesvos, who opened their families and offered a warm embrace to the suffering Syrian refugees.

Another highlight of this year’s festival is focus on Ukraine, with the Myroslav Slaboshpytski Retrospective, which includes short films of the acclaimed Ukrainian director, best known for his debut The Tribe. Along with this, the Ukraine Female Filmmaker Focus offers a variety of Ukrainian shorts directed by young upcoming female filmmakers. Covering a range of themes and styles, the Ukrainian focus brings to the festival a taste of the Ukrainian life, history and politics.

The 22nd Encounters Short Film and Animation Festival runs from 20th-25th of September in Bristol. Just click here for more information.