This is the alphabetic list of the dirtiest movies ever made, as carefully selected by this humble film critic. I’ve whittled down over a century of films and assigned each one of them to a letter of the English alphabet, beginning with a numeric one. The order of the 27 films goes like this: 12 (as in 12 Angry Men), A, B, C, D,… all the way to Z!

I’ve always looked at cinema as being like a kid in a sweet shop. There’s an abundance of choice – multiple lifetimes worth. In keeping with this metaphor, this series will include cinema from different decades of film history, and from across the world. Some will be driven by the personal more than others, but each is a dirty gem!

From Sidney Lumet’s 1957 courtroom drama 12 Angry Men (the numeric entry), and Justine Triet’s 2023 crime and courtroom drama Anatomy of a Fall (letter B), we continue our 27-month-long odyssey with a story about what happens when suburbanites strike back.

…

.

Joe Dante’s 1989 American black comedy The ‘Burbs, is the first choice in this list that’s driven by a personal connection. It’s one of the most watched films by this critic, whose VHS recording began to show signs of wear and tear back in the day.

Ray Peterson’s (Tom Hanks) humorously absurd, horror laden nightmare sequence served as an introduction to William Friedkin’s The Exorcist (1973) and Tobe Hooper’s The Texas Chainsaw Massacre 2 (1986). A possessed Linda Blair projectile vomiting terrified him so much that it put him off watching The Exorcist for some years. So, there’s quite a personal history with this film.

Still, he finds himself disappointed when new neighbours in his street fail to pave the way for some silly heroics, by turning out to be respectable citizens unlikely to be burying bodies in their back garden. Either movies are more fun than reality or he’s a little bit f***ed up in the head (wink emoji)!

From the outset, Dante’s black comedy is visually playful. Jerry Goldsmith’s creepy score, filled with nervous anticipation accompanies the Universal logo. The camera zooms in on Earth, hurtling down towards North America until it picks out Mayfield Place, a quiet suburban cul-de-sac. Peterson, barefoot and in his nightgown, investigates strange noises coming from his neighbour’s house in the dead of night.

The ‘Burbs begins as a horror film before cutting to its light and breezy title sequence. A newspaper delivery kid on a bicycle gives us a tour of Mayfield Place and its residents. It’s not long before the plethora of great lines begins, when retired US army Lieutenant Mark Rumsfield (Bruce Dern), a Vietnam veteran steps back in dog shit on his lawn. He marches over to his neighbour Walter’s (Gale Gordon) house, and in an amusingly angry tirade, warns Walter that his French poodle Queenie has taken her last dump on his lawn. If he catches her again, he threatens to staple her ass shut.

.

Not just another comedy

The opening scenes set the stage for a playful tonal mix. The back and forth between absurdist comedy, with a satirical edge about the suburbs, and horror, pivots to a fun Ennio Morricone-like score and the march of the western heroes in one scene. Then there’s the inclusion of The Exorcist and The Texas Chainsaw Massacre 2, before Ray is seen watching Mister Rogers’ Neighbourhood (Rogers, 1968-2001). The ‘Burbs also reimagines the opening of David Lynch’s romantic take on suburbia in Blue Velvet (1986), but in reverse, expressing the pretence of normality instead of revelations about the dark social underbelly. In its own unique way, The ‘Burbs is Dante’s personal nostalgic celebration or love letter to storytelling and also the meeting point between light and darkness.

The ‘Burbs is made up of layers of fantasy that refuses to ground itself. To fully appreciate Dante’s black comedy, we should look to screenwriter Dana Olsen’s inspiration – Alfred Hitchcock’s Rear Window (1954) and his suburban upbringing. Dante and Olsen take Rear Window and cross it with Richard Donner’s adventure comedy, The Goonies (1985). Instead of kids, its adults finding their inner child and reawakening the adolescent desire for adventure, during one boring Holiday Weekend. It compares to other films besides Rear Window about neighbours watching neighbours, among them: Tom Holland’s Fright Night (1985) and its remake, D.J Caruso’s Disturbia (2007), and Michael Mohan’s The Voyeurs (2021).

35 years after its release, The ‘Burbs remains an endlessly rewatchable cult favourite with an abundance of comedic absurdity – an infra-red night vision scope to spy on their new neighbours, the Klopeks from the behind dustbins, a ransom note for a dog, and Rumsfield in camouflage army uniform on his roof with a rifle and binoculars.

.

Then it gets dirty…

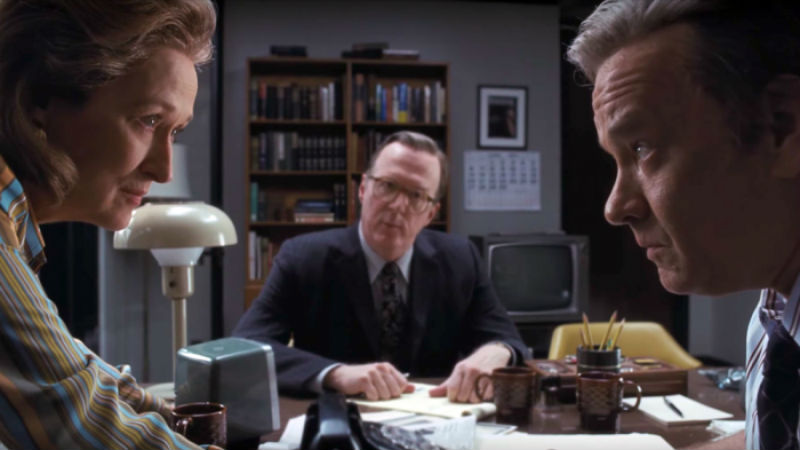

The ‘Burbs also features one of the most chilling scenes in genre cinema, when Art Wiengartner (Rick Ducommun), Ray’s quirky and paranoid neighbour recounts the story of Skip, the Hinkley Hills soda jerk (soda fountain operator), who murdered his family one sweltering summer when they were kids. In this scene, Ray, Art and their young neighbour Ricky’s (Corey Feldman) evening stroll around the neighbourhood becomes a scary story around the campfire, revelling in deconstructing the naïve nostalgia for the good old days. The chilling story with a tongue in cheek vibe is brilliantly judged by Olsen’s writing, Hanks and Ducommun’s performances, Dante’s direction and Goldsmith’s score.

Art’s story and The ‘Burbs itself emphasises the need to be afraid of man instead of the monster, and how the monster is and was always an extension of man. This plays on Dante’s earlier werewolf film, The Howling (1981), and echoes this transition to man as a new object of fear in the 1960s, where Hitchcock’s Psycho (1960) and Michael Powell’s Peeping Tom (1960) were seminal films. The ‘Burbs is also connected to films about intrusion on the community, like Hitchcock’s Shadow of a Doubt (1943) and Orson Welles’ The Stranger (1946). This reveals the deep narrative roots of Dante’s black comedy and its place in narrative traditions.

The humorous antics and fun of the film have a way of concealing any themes and ideas, even in hindsight. The ‘Burbs, however, taps into decades of American paranoia. While there’s a lore about different endings, the real horror of the film lies in the simple but effective ending chosen. It maybe offers a propagandist and righteous slant on a commentary that appears to want to critique self-fulfilling prophecies, the intolerance and prejudice of quaint suburbia and the American fear of the “other.”

The ‘Burbs gives its characters and audience the heroic, romantic ending we want, perfectly punctuated by Art’s rousing statement to news journalists: “I think the message to, uh, psychos, fanatics, murderers, nutcases all over the world is, uh, ‘do not mess with suburbanites, because, uh, frankly we’re just not gonna take it anymore. Ya know, we’re not gonna be content to look after our lawns and wax our cars, paint out houses.'” Then, there’s Ray telling Ricky to look after the neighbourhood while he’s on vacation, to heal his urban war wounds. Amid these dramatic heroics, the discerning viewer will be distracted by something more ominous in its subtext, especially given the Eastern European antagonists.

This is the third one in the series of Paul’s 27 Dirtiest Movies of All Time (one for each letter of the alphabet, plus a numeric film).