Russian roulette. You put a bullet in the chamber of a revolver. You spin the chamber. You put the barrel to your head and pull the trigger. The chance is one in six you shoot yourself. Theoretically, the chamber containing the bullet is the heaviest, so that sinks to the bottom and you’re emptying an already empty chamber. But that’s not always the case. Also, if the spin is arbitrarily stopped, your chance is definitely one in six.

Russian roulette is about as dirty a pastime as you can imagine. Especially if players are not taking part of their own free will and if spectators are gambling money on the game. Games in which the participants are gambling their very lives.

Games of Russian roulette take centre stage in The Deer Hunter and function as its central metaphor. It’s a series of snapshots from the lives of a group of Pennsylvania steelworkers who enlist in the Vietnam War.

In the first hour, Michael (Robert De Niro), Nick (Christopher Walken) and Steven (John Savage) leave their factory workplace and, prior to shipping out to ‘nam, they attend Steven’s wedding and party then go on a deer hunting trip.

Surprisingly, the wedding party seems to take up the best part of the first hour. It’s unclear how much is scripted and how much improvised but Cimino is clearly fascinated by setting up such scenes for the camera and letting them play out with actors. These scenes feel at once well prepared and open to anything that happens on camera, lending them a convincing realism.

If both wedding party and deer hunt showcase a degree of male horseplay, the hunt also hones an aspect of Michael/De Niro who by the end of the film has emerged as its main protagonist. As far as the hunt goes, Michael takes only one of his friends seriously: Nick. Certainly not Stan (John Cazale) who wants to borrow Michael’s spare pair of boots having forgotten to bring his own.

Even so, Michael goes off on his own to hunt and shoot a deer, determined to do so with a single shot. And he succeeds. The single shot anticipates the subsequent Russian roulette where a single shot decides a participant’s fate.

About an hour and 10 minutes in, just when you’re wondering why anyone should refer to this as a war film aside from its young men about to go to war theme, an edit abruptly cuts to the Vietnam War. Michael is lying hidden in the dirt as an enemy soldier opens a trap door hiding terrified villagers and tosses in a grenade. At once shrewd and possessed of a righteous indignation, Michael is soon wielding a flamethrower against the enemy. After which the rest of his unit, including Nick and Steven, show up.

Another cut and the three are held prisoner waist deep in water below a bamboo hut on stilts above a river. Steven is not coping well. In the hut above, other prisoners play Russian roulette at gunpoint for their captors’ amusement and gambling bets. Keeping his head, Michael devises a plan to get three bullets put into the revolver for the game as the trios only possible hope of escape.

In line with De Niro’s physicality and commanding presence – he’d already played three of his great Scorsese roles Mean Streets (1973), Taxi Driver (1976) and New York, New York (1977) plus Coppola’s The Godfather: Part II (1974) – he does indeed break the trio out in a tense escape sequence.

In the 1970s, a new De Niro film was a cultural event. He articulated the emotional arc of a generation and you had to see it, at least if you were male. This ceased to be the case somewhere in the 1980s. It’s hard to think of an actor (male or female) since for whom this is true to the same degree.

Michael/De Niro takes centre stage in further sequences in Saigon and Pittsburg. Nick disappears into Saigon’s dangerous and shady Russian roulette gambling netherworld under the patronage of a mysterious, enigmatic French promoter (real life Bangkok restaurateur Pierre Segui) while Steven has been reduced to life in a wheelchair in a military nursing home. Peter Zinner’s groundbreaking editing means that Nick/Walken’s slow personality disintegration is fed to us in devastatingly effective bursts.

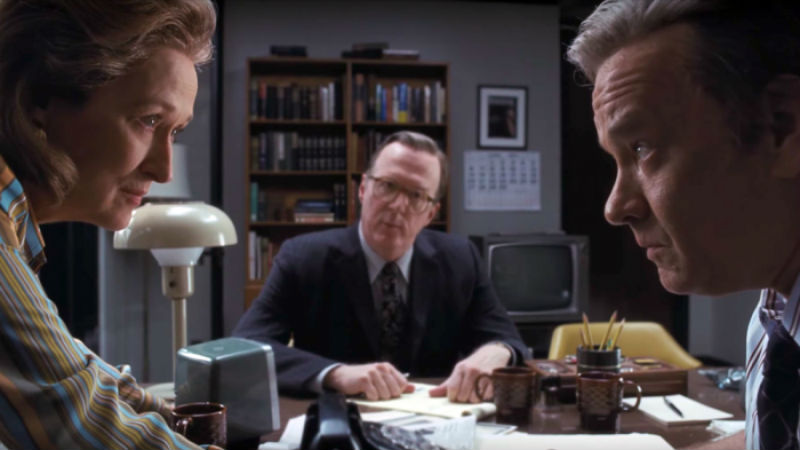

A Pittsburgh subplot also develops Nick’s girlfriend who becomes involved with Michael when he returns but Nick does not. She’s brilliantly played by Meryl Streep who turns a minor bit part into something very special indeed.

Russian roulette not only causes Steven’s trauma and Nick’s disappearance but also affects Michael’s attitude to the world around him. Back in Pittsburgh, he avoids a ‘welcome home’ party. He goes hunting again but can’t bring himself to shoot a deer. He’s clearly not the “man” he once was. Whether this is good or bad is open to debate – perhaps that’s part of what makes this such a great film.

The lethal game provides a wider metaphor too. The war kills and damages people at random. But perhaps life as a steel mill worker isn’t so good either, otherwise why would enlisting in a war seem such a good idea? Michael talks about shooting the deer with “only one shot”, but in the Russian roulette scenes “only one shot” keeps coming again and again until it kills someone. War is about lots of “only one shot”s one after another. It’s also the case in a wider sense, outside the war context, that you only get one shot at life but life can take as many shots as it wants at you and any one of them could prove fatal.

It may be 40 years old and ostensibly about the Vietnam War, but The Deer Hunter actually tackles deeper issues – not only how the horror of war changes people but also how people deal with their lot in life generally. Made in 1978, it looks as fresh today as it did on its original release. A beautifully judged, dirty masterpiece.

The Deer Hunter is back out in the UK in a 4K restoration on Wednesday, July 4th. Watch the film trailer below: