WARNING: THIS REVIEW CONTAINS SPOILERS

Glancing over the past decade of Nicolas Cage’s extensive filmography one cannot help but be stunned by the glimmers of exceptional performances within the mire of otherwise below par straight-to-streaming movies. Examples such as Joe (David Gordon Green, 2013), Mandy (Panos Cosmatos, 2018), Colour Out of Space (Richard Stanley, 2019), The Unbearable Weight of Massive Talent (Tom Gormican, 2021), and Pig (Michael Sarnoski, 2021) are the standout performances from Cage’s past decade of film work. Yet, these five films sit within an expanse of 42 films that have been released from 2013 to 2023. Not good odds. In fact, those percentages would ordinarily knock any other actor out of the game for good, yet despite this Cage’s popularity is as strong as ever. His eccentric performances within even the most dreck of films is greeted with anticipation and appreciation. It’s rare these days, but it’s always a wicked delight to witness Cage on the theatrical screen. His presence, though diminishing somewhat with age and by the countless sup-par films, pulsates with movie-star quality that has vanished from many of his acting peers who began their careers in the same era.

Cage’s eccentric performances within even the most dreck of films is greeted with anticipation and appreciation. Never mind that the script is beyond shoddy, the direction a dud, or a narrative that simply sucks, Cage emerges victorious among his loyal fanbase who become feverish for the next entry. I’m an absolute sucker for Cage’s work and although above I have pulled out five prime examples of great work from the past ten years, I admit my love of Cage’s performances has meant me revisiting films such as Dog Eat Dog (Paul Schrader, 2016), Mom and Dad (Brian Taylor, 2018), and Prisoners of the Ghostland (Sion Sono, 2021) over again. And this is just the later works. Any new Cage film that lands on streaming is lapped up in an instant.

Dream Scenario, the third feature from Norwegian film director Kristoffer Borgli returns Cage back to the big screen and gives him his best critical reviews since Adaptation (Spike Jonze, 2002). The film concerns Paul Matthews, a tenured college biology professor with aspirations to write a book on the habits of ants who suddenly and inexplicably begins appearing in the dreams of people all over the world. At first, his presence within these dreams is as a bemused spectator, but eventually his presence becomes more intimidating and violent. His dream persona begins a campaign of murder, torture and rape against those who dream him.

His own reality falls apart as his fame becomes notorious. People he knows, including his own students, distance themselves from him and his dreamt-up atrocities. Unable to control the perception that people have, Paul teams up with a marketing start-up to try and turn his fortunes around and make his fame a more positive experience. Instead, the company guides him towards embracing the darker elements of his fame. Alongside Paul’s rise to fame is the pressures on his family and work colleagues. His wife Janet (Julianne Nicholson) copes by throwing herself into her work (and possibly an affair with a co-worker), while his two daughters Sophie and Jessica (Lily Bird and Jessica Clement respectively) deal with the social pressures from their peers at school. Paul’s boss and co-workers try their best to accommodate his notoriety, but he is eventually laid off when it becomes clear his students can’t overcome the trauma of being sliced and diced up in their dreams.

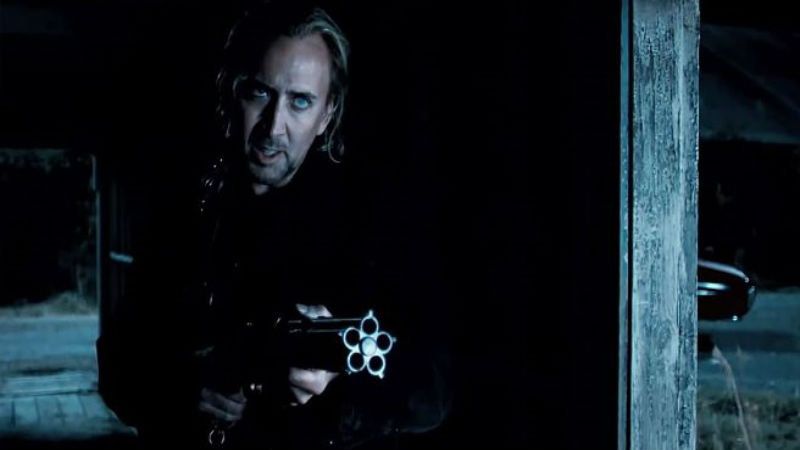

After a few months, Paul fades out of peoples dreams, but his excursion leads to the creation of a new dream-traveling technology that allows a group of ‘dreaminfluencers’ to enter the subconsciousness of anyone and conduct product placements within the dream. Dream Scenario intention here seems to offer a message that dreams are the last refuge against the ever-increasing commodification of our lives. If they are intruded upon, we really do begin to lose ourselves. And loss is what eventually occurs. Paul, now separated from Janet, goes on a book tour of France (where oddly his violent dream behavior was enjoyed) to sell his autobiography Dream Scenario which has been translated to French as “Je Suis Un Cauchemar” (“I Am a Nightmare“, in free translation) with a frightening new cover that features Paul’s face looming in shadows. While in France, Paul uses the dream technology to enter Janet’s subconscious and try to reconcile with her there.

Cage playing the role of a now infamous personality mirrors his own journey. Once considered a serious-minded actor of relatively high-brow material, his later work in film matched with his outrageous personality and extravagant lifestyle has made him a kind of self-replicating internet meme whose acting craft is sidelined in favor of hammed-up performances and exaggerated tics. Whatever scene, or small moment that can be captured and taken out of context, adapted, and spread through the wires is the predominant outcome of Cage’s work. This is a shame as, for once, Dream Scenario offers Cage enough gravitas and nuances to show that he can summon great complexity when the material calls for it. He portrays Paul as a man being crushed under the weight of disappointment that life has delivered upon him. Cage gives Paul a heap of nervous physical and verbal tics that signal a life of compromise and giving way to the ambitions of others. He is a weak man who is suddenly given the opportunity to express influence and knowledge, but hasn’t got enough control of his situation to make it happen. Instead, circumstances run away from him and the perception of him overtakes his personality. It is evident that this perception over reality has also occurred to Cage himself. We have websites such as Nic Cage as Everyone, YouTube parody videos such as ‘Nicolas Cage’s Agent’, podcasts dissecting his film work, and countless memes and gifs that take his smiley face contortions out of context. Cage isn’t in control of any of this. It’s a product.

Dream Scenario isn’t perfect. The introduction of the dream-technology late into the narrative feels very tacked on and offers a Black Mirror-style (David Slade, 2018) technological reading of the film’s premise and a last-minute stab at social commentary and the commodification of dreams that seems forced and unnecessary to the personal trajectory the story takes. The dream device technology acts as a narrative device itself that allows Paul to access Janet’s dreams to attempt a reconciliation. It might have felt more satisfying and more real if she would have dreamt Paul up naturally all by herself. After all, Janet expresses concern that Paul never seems to appear in her own dreams so having him literally appear as the ‘man of her dreams’ would have been a fitting and uplifting conclusion. Instead, after placing much investment in Paul’s, the audiences are left not knowing if he’ll be okay in the end, or if the darkness of his dreamt actions will overtake his actual life.

While the bulk of the marketing has been focused on Cage’s performance, credit must also be given to Julianne Nicholson as Paul’s long suffering wife Janet, Dylan Gelula as Molly, a marketing assistant who attempts to make her erotic dreams about Paul come true, Michael Cera as Trent the aloof head of the marketing agency, and the film’s best kept secret, and Tim Meadows as Paul’s sympathetic boss. While Dream Scenario isn’t an ensemble piece as such, the presence of these actors elevates the film further and gives Cage plenty to bounce off of. Borgli’s direction and editing gives the film a fun and easygoing pace that only becomes cluttered and unsure of itself towards the conclusion.

Cage recently stated that his acting career is winding down with maybe four or five films left before retirement. This would be a great loss. Dream Scenario gives Cage an actual age-appropriate role that offers a whole new arena for his abilities. If he bails out within the next year or two a whole host of potential films could have seen Cage build upon his work here. After everything that has come before, the highs, the lows, the hits, the flops, the odd hair styles, the madness, and the brilliance, the next stage of Cage could be the most subtle and most interesting era. I guess we should dream that it happens.

Dream Scenario is in cinemas across the UK on Friday, December 8th.