Panos Cosmatos (pictured above) subverts low-brow genre film making by blending exploitation subject-matter and crafting it into beautiful, cinematic events of emotional, visual and sonic intensity. Carving out a new genre of film, Cosmatos draws from a global heritage of art and artefact, high and low, to tell stories that resonate, captivate and obfuscate with equal measures of sledge-hammer force and artful finesse.

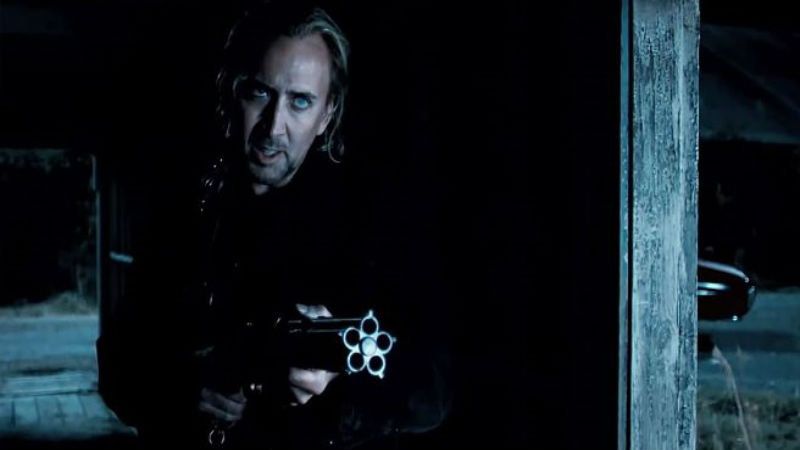

His second feature film Mandy (after the 2008’s critically acclaimed Beyond the Black Rainbow) stars Nicolas Cage, Andrea Riseborough and Linus Roache and is about set-fire to everything we thought we knew about cinema and story-telling. You can read our exclusive review of the film by clicking here, where Stephen Lee Naish compares Cosmatos to Lynch and Kubrick.

Lara C. Cory met with Panos Cosmatos as he travelled to London for his film premiere at the London Film Festival on October 11th. The film was launched in cinemas across the UK the following day. They talked about the origins of Mandy, why he took a decade between his two films, working with Nicolas Cage and unusual “paces”. Read on and find out more!

…

.

Lara C. Cory – It’s been a long time since your first film Beyond the Black Rainbow in 2008. Do you remember the kernel of how Mandy began in your imagination and when you knew it would be your next film?

Panos Cosmatos – It was right when I was still writing Beyond the Black Rainbow [pictured below; all other images from Mandy], and looking back on it now I realise now it was sort of like an antidote to BBR which was all about suppressing my emotions and grief [Panos’s father, director George P. Cosmatos died aged just 64 in 2005]. Unconsciously, I think I needed to purge my grief in a volcanic eruption of feelings. I chose the revenge genre for its innate emotionality and operatic qualities.

LCC – You deliver such emotional depths in your films, in spite of the minimal dialogue and simplistic plots. In a cinematic landscape where so many fail on this level, how do you get it so right?

PC – I think because I’m morbidly fixated on the idea of simplicity in a weird way. It’s reactionary too, because when I was writing these films, the mid 2000s, films had become preoccupied with intricate plot lines. But they were only an illusion of complexity because emotionally and tonally they were not complex films. I wanted to do something simple; start with a simple story and build up a rich emotional, sonic and visual experience around that. To me, the story is fuel that drives the hot-rod. It doesn’t need to complicated to be interesting or powerful.

LCC – The pacing of your films is noticeably slower than most releases today. Can you talk about your decision to pace Mandy, in the first half anyway, as gently as you did?

PC – Beyond the Black Rainbow was deliberately slow because I was interested in the zone-out, hypnotic, trance-like quality of 35mm film. I wanted people to lose themselves in the film and not feel pushed forward the whole time. Mandy was a bit more propulsive, I think of Beyond the Black Rainbow as slow speed, and Mandy as medium speed. I wanted the audience to sink into this metaphorical lake of this reality, let them become comfortable so I could slowly tear it apart.

LCC – Not only Cage, Roache and Riseborough in Mandy, but Michael Rogers in Beyond the Black Rainbow have all delivered extraordinary work. How you manage to draw out such incredible performances from your actors?

PC – You have to trust the actors and give them room to breathe. When Linus came in he started doing his lines super-fast thinking it’s what I wanted. So, I told him to really slow down and he was a bit shocked but delighted that he could take his time. In modern film and TV there is high premium on constantly propelling things forward in a very artificial way. There’s something beautiful about letting an actor speak for a long time. To see the characters you’ve created come alive is really magical see and I too want to revel in it.

LCC – There seem to be little clues that signpost your favourite films and directors throughout Mandy. Who are some people and films that have influenced your style?

PC – The film maker that sparked it for me when I was making Beyond the Black Rainbow was French exploitation filmmaker Jean Rollin, who made these weird, ultra-slow art-house vampire films. That triggered something for me; I saw this blending of this extreme art-house technique with very low-brow exploitation subject matter. For Beyond the Black Rainbow the DP and I drew on a lot of very specific frames and references from other films to create the colour palettes and textures, but for Mandy I felt more confident to draw on my own experiences. A lot of the colours and tones come from moments in my life, for example, sitting on the roof of the car and seeing the smoke illuminated by the tail-lights in the rear-view mirror, and growing up in the pacific northwest and how that looks and feels, especially at night.

I’ve always loved villains that are perverse ego maniacs. And definitely Frank Booth [from David Lynch’s 1986 Blue Velvet] and the films of Stuart Gordon have these villains that are these delusional ego maniacs. I like that as a starting point. These people who are kind of pathetic more than they are scary, and when their self-image is threatened that’s when they become scary.

LCC – Both Mandy and Beyond the Black Rainbow are set in 1983 – why?

PC – I was delving into the things that meant a lot to me as a kid, and, I guess I see that year as signifier of a mythical imaginary reality. Before my dad died I rejected the 1980s as ridiculous. I stopped watching genre films and was more interested in French new wave and foreign films, it was fresh to me. But after dad died, I realised that these low-brow genre films were equally important to me and spoke to me in an equally powerful way. I wanted to merge them together.

LCC – You’ve said that music plays a big part in your creative processes. Can you tell me a bit about the sound palette you used during the making of Mandy?

PC – It’s all over the map in a way. I usually compile a playlist for each project which I then have to whittle down when it gets out of control. Often, I’m searching for the opening title sequence track and it takes me a lot of time trying to find the right one. I spent years looking for the title track for Mandy and out of the blue one day, my wife started playing me Starless by King Crimson, her dad was a big fan. The second I heard it I knew I’d found the right one, finally. The playlist I had by the time I spoke to Johann was stuff like Van Halen’s Sunday Afternoon in the Park, the Flash Gordon soundtrack, and this gentle, almost Spanish guitar instrumental by Black Sabbath called Laguna Sunrise which in my head, was Mandy’s theme.

LCC – Knowing the sort of the music Johann was known for, it must have been a bit of risk getting him on board considering the style of Mandy. Do you remember what it was like when you heard his first submissions?

PC – Yeah, it can be a bit nerve-racking to hear that first piece of music but I’ve been lucky so far with both Sinoia Caves and Johann. I didn’t think he’d want to work with me. I think of his work as very austere, but after talking with him I realised he grew up as an Icelandic metalhead and we had a lot of the same touchstones growing up. I immediately connected with him, in a weird way he kind of reminded me of my father growing up. He was gruff but very open. When I showed him the playlist he responded to everything on it and really liked the idea that this would be the starting point. We didn’t want to ape it, we wanted to interpret the songs via the film. It was like Christmas getting the first tracks from him. I feel like we only started to scratch the surface of what we could’ve done.

LCC – Do you think you’ll leave plenty of room before your next film, or have you got something lined up that you want or have already started on?

PC – I don’t what I’m gonna do. Hang out with the cat for a while.

LCC – Was there any reason you called her Mandy?

PC – Because of the Barry Manilow song. I absolutely love it!