A man is at a house party. His name is Fred Madison. He’s handsome, but he feels out of place. He doesn’t think he’s hip enough for the younger crowd. He’s a jazz musician, so probably can’t appreciate the pounding groove of the dance music playing loudly. His wife is also flirting madly with the host of the party. He goes to the bar for a drink. In walks another man. He’s much older, he’s dressed in all-black, his hair is parted expertly down the middle and slicked to each side. His skin is pasty white, and he has no eyebrows. Fred gives the man a curious look. Oh no, eye contact has been made. Fred quickly looks away, but the other man keeps his eyes fixed on Fred and casually walks over with a huge smile on his face and wide eyes. The music in the background suddenly drops in volume. “We’ve met before, haven’t we?” the man asks Fred. Fred can’t recall ever meeting this strange-looking man. And this guy is impossible to forget.

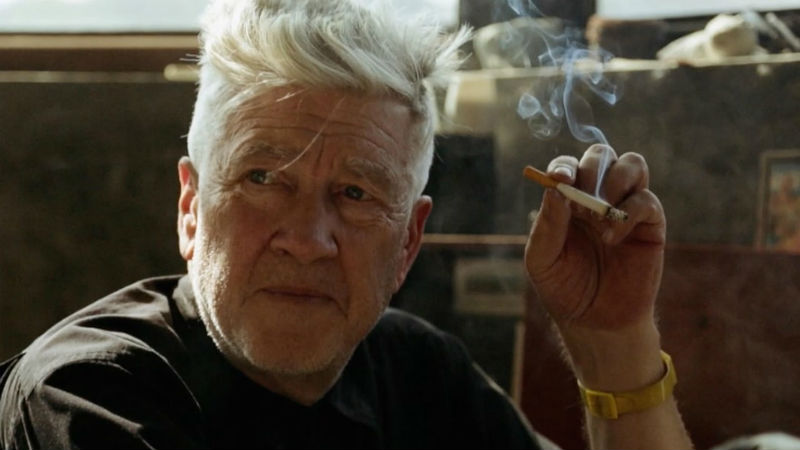

And so, begins one of the strangest and most alluringly hypnotic scenes in cinema. This comes from David Lynch’s 1997 neo-noir Lost Highway, which is currently flabbergasting audiences with a gorgeous 4k restoration. The conversation the two men have goes nowhere. An absurdist back and forth. It doesn’t tell the audience anything about the narrative as such, but it does give the impression of how we’re meant to feel for the remainder of the film. Disturbed, uneasy, confused, weirded out, immersed, amused, and even vulnerable. All these things all at once. The scene, like the whole film, is a fever dream and only really makes sense in that context when all context is ripped away. The man, simply referred to as the ‘Mystery Man’ never stops smiling throughout the whole exchange, even when delivering sinister threats.

The plot is simple. Fred (Bill Pullman) answers his intercom buzzer one morning to a man’s voice informing him that “Dick Laurent is dead.” Fred and his wife Renee Madison (Patricia Arquette) then begin to receive videotapes that contain recorded footage of the outside of their house. As more tapes arrive, more and more footage is revealed, until one tape shows the couple asleep in bed. They call the police to investigate the tapes and attend a house party to take their minds off the events. Fred has a weird conversation with a mysterious man (Robert Blake). See above. Eventually a videotape arrives that has Fred screaming and crying over Renee’s bloody corpse. Fred is arrested for murder and sentenced to death. While in his cell he is inexplicably replaced by a handsome younger man named Pete Dayton (Balthazar Getty). Pete is collected by his parents and returns home. Eventually he returns to his job as a car mechanic. Pete is also a personal mechanic to Mr. Eddy (Robert Loggia), who is known as Dick Laurent, a local gangster, and porn aficionado. Pete begins a passionate relationship with Eddy’s girlfriend Alice Wakefield (also played by Patricia Arquette in a blonde wig).

When their relationship is discovered by Mr. Eddy, Pete and Alice rob a wealthy pornographer and go on the run. With their stash of stolen loot, they head out to the desert to find Alice’s fence (the Mystery Man from our earlier discussion) who can sell the goods for them. In the desert they have sex on the sand. Pete then turns back into Fred. Fred finds Mr. Eddy and with the help of the Mystery Man kills him by slashing his throat. Fred then returns to his home and whispers into the intercom that “Dick Laurent is dead.”

See, simple. If you ignore the unexplained identity shifts, the way most of the characters seem locked in a psychogenic fugue, and the way the film unfolds like a Möbius loop it’s almost fit for an episode of Columbo or Murder, She Wrote.

Lost Highway is a strange concoction. It implores you to go along with it and explore and unlock the mystery it presents. It gives you all the tools you need, all the clues are there in the film. It also throws so many forks in the road, so many destabilizing moments and performances that what you think you know about the film suddenly proves incorrect. Or maybe you’re just overthinking it. It’s a mystery film in a genre sense, but also a mystery film in its layered complexity. It never fully unlocks.

I remember the first time I watched Lost Highway. It was sometime in the early 2000s. I was on a Lynchian trip after seeing Blue Velvet (1986) and my housemate at the time had purchased a VHS copy from the sale bin in the local Virgin Megastore. We’d had several beers and decided to watch the film as it struck close to 11pm on a Saturday night. My housemate was asleep within ten minutes and caught up in a dream that probably made more sense than what was unfolding and baffling me on screen. I was paralysed, mostly in fear, but also in wonderment at the images and sound and the sense of dread the film instilled. Like the fixed grin that remains on the Mystery Man’s face. I was just as locked in a wide-eyed expression of terror and glee.

I retired to bed sometime past 1am. I didn’t sleep. How could I? Unused and unknown parts of my brain were fired up. The next morning, I tried to explain the film (quite badly) to my hungover housemate. They seemed relieved to have missed it.

Watching the 4k restoration on the big screen gave me a similar experience to that first time around. It’s a thing of absolute beauty. The shadows and light are exquisite. The soundtrack is penetrative. Heavenly verses of Song to the Siren by This Mortal Coil drift in and sooth while the grinding belabor of Nine Inch Nails and Rammstein leap out. The abstract and stilted performances are harrowing, yet also absurd and funny as if a laugh track should have been employed after every line much like Lynch would do later for his absurdist short film series Rabbits (2002). My cheeks and jaw ached like hell the next day from the permanent grin fixed to my face while in rapture of the film.

I don’t really care about trying to make sense of Lost Highway or trying to unpick its sublime mystery. I don’t need it explained to me why Fred suddenly and inexplicably changes mid-way through into Pete. It’s confusing as it is perfectly reasonable for a film that wants you to remain on the knife-edge of unnerved. I like that a film can interpretated in many wats and that its author doesn’t care clarify the actual meaning or events that take place. It means the film is ours in some way. I want Lost Highway to remain obtuse and unreadable. Sometimes we just need things to stop making sense. Like the world we live in.

“We’ve met before, haven’t we?” Yes, it was intoxicating and weird, but I’ll see you again. It’s been a pleasure talking to you.

A 4K restoration of Lost Highway has toured selected US and UK cinemas in the past couple of months. Stay tuned for a ultra-HD Blu-ray release.