The mid-19th century novel The Personal History Of David Copperfield is considered Charles Dickens’ masterpiece. Narrated in the first person by the eponymous David, it tells of one man’s life from birth through a series of adventures and encounters with a motley crew of relatives, friends and associates that seem to span the social breadth of Victorian England.

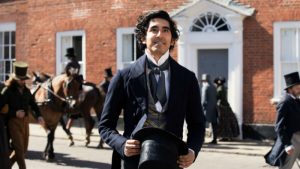

To cut the novel’s tale down to a manageable movie length, director Ianucci and his co-writer Simon Blackwell have dumped certain characters and subplots to focus on others. As with the director’s previous outing The Death Of Stalin (2017), the final film half works yet is beset by strange casting choices – actors playing Russians sporting a variety of English dialects in Stalin, various BAME actors playing roles that aren’t always entirely believable in terms of their ethnicity in Copperfield. That includes the film’s lead Dev Patel, who plays David convincingly as a wide-eyed innocent.

There’s a great deal of racism around in the 21st Century: it’s hard to believe there wasn’t considerably more in the 19th when few were trying to address those issues, yet no-one seems to notice Patel’s obvious ethnic background. When he’s sent to live with the family of his mother’s kindly housekeeper Clara Peggotty (Daisy May Cooper), she and her husband have adopted a number of orphans, one of whom, Ham (Anthony Welsh), is black, which could make sense. Later, however, when the mother of David’s privileged, white, secondary school friend James Steerforth (Aneurin Barnard) is played by the black actress Nikki Amuka-Bird, the ethnic casting is distinctly unbelievable. Pursuing the colour blind casting still further, Ianucci casts Chinese British actor Benedict Wong as Wickfield, the financier ultimately ruined by alcoholism and another terrific black actress, Rosalind Eleazar, as his daughter Agnes.

On one level, colour blind casting sounds great and if you view the whole thing as a satire not based on any specific, historical place and time then it’s not a problem. Sadly, Dickens is very much a man writing about the 19th century and even though all the actors are fine in terms of performance, the BAME casting sometimes doesn’t work. I’m not saying the entire cast should be white – there were certainly some BAME people around – but I’m calling for an attempt at historical accuracy, a practice which should take precedence over the accidental pursuit of a politically correct fantasyland that never was.

Outside of the ethnic controversy, Ianucci proves highly adept at casting Dickens’ characters. Dev Patel carries the film well and other highlights include Hugh Laurie’s Mr Dick, a sweet if mentally ill man who believes Charles I to have deposited his thoughts in his (Mr. Dick’s) head and Ben Wishaw’s suitably ingratiating social climber Uriah Heep. Tilda Swinton doesn’t appear particularly stretched in the role of David’s controlling and donkey-hating aunt Betsey Trotwood.

Dickens wanted to highlight the problem of want in Victorian society and the film represents this aspect of his writing well. The constant hounding of Micawber (Peter Capaldi) for his debts results in one memorable scene where his baby in its pram is suddenly moving down the hall as the bailiffs grab under the front door and pull the hall carpet out underneath it. Equally impressive are the scenes of David working as a child in a bottle factory where the machines are too tall for him to operate properly.

Elsewhere however, as with Stalin, one struggles to remember that Ianucci is the comic genius behind television’s political comedy series The Thick Of It (2005-2012) and its superb feature film spin-off In The Loop (2009, in both of which Peter Capaldi so brilliantly played ruthless and foul-mouthed spin doctor Malcolm Tucker). Maybe he’s better at portraying contemporary rather than period stories. That said, if his Copperfield never quite scales the genuinely funny comedic heights of The Thick Of It, or even reaches the foothills, it at least gets Dickens’ remarkable characters onto the screen and is not without its moments.

The Personal History Of David Copperfield is out in the UK on Friday, January 24th. On VoD in June.