The story opens up with a young man singing the famous fado song Estranha Forma de Vida (Portuguese for “Strange Way of Life”). He is sitting on the porch of a large and precarious wooden house, one of those that you see in every spaghetti Western movies. His gaze is firm yet sad. The image will immediately evoke Caetano Veloso singing Cucurrucucu Paloma in Almodovar’s Talk to Her (2002). Except that the man singing isn’t Caetano Veloso. Yet the wistful warble indeed belongs to the Brazilian singer and composer, a recurring voice in Almodovar’s oeuvre. The tone is set. This is a melancholic drama. A queer Western infused with Latin flavours.

The story evolves around middle-aged sheriff Jake (Hawke) and his lover from 25 years earlier Silva (Pascal). The two are unexpectedly reunited in an intense carnal evening, but the sheriff suspects that Silva’s sudden apparition this has nothing to do with affection. That’s because Silva’s son is being investigated by the Jake, and could be tried for murder. In the morning, the two men consistently vet, question and challenge each other’s sentiments and motives, in an elaborate duel between reason and emotion. They reminisce the past. A flashback reveals that they first fell in love in an evening doused in wine and pierced by bullets.

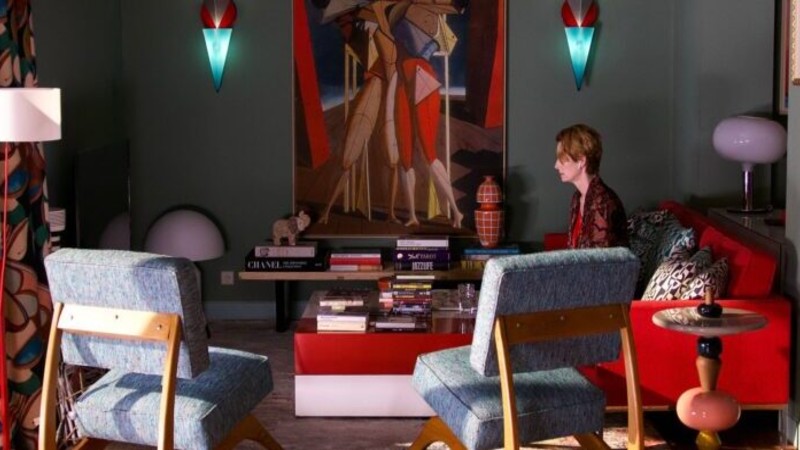

Vivid red is prominent throughout the film, from the opening title to the wine and the blood that inevitably washes their sins. The evocative colour is an Almodovarian trademark. The landscape is hot and arid, much like the homosexual romance that is not allowed to blossom. Instead the two men were forced into a life of uncomfortable conformity, the unfulfilled existence to which the song and the movie title allude.

The movie is filmed in the dusty Tabernas Desert near the Andalusian town of Almeria, a place with a climate and vegetation very similar to the Old West (where the story takes place).

With a fairly predictable ending, Strange Way of Life adds very little to Almodovar’s impressive filmography, except perhaps for a change of language and geography. The message about unrequited domesticity (ie the two men could never live as an ordinary couple) is banal and redundant. Strange Way of Life is some sort of unpretentious Latin tribute to Ang Lee’s Brokeback Mountain (2005). Not a movie that will stay with a you for a long time. Not a waste of your time, either.

Strange Way of Life premiered at the 76th Cannes International Film Festival, when this piece was originally written. The film was out of competition, presumably because of its duration of just 31 minutes. This is the second time the Spanish director has directed an English-language film, the first one being the equally short The Human Voice (three years ago in Venice). Because of its unusual length, the movie is unlikely to see widespread theatrical release. On the other hand, it may find peculiar distribution strategies. Almodovar’s 2020 film was shown in UK cinemas followed by a real-time nationwide Q&A with the Iberian filmmaker and British actress Tilda Swindon.

In cinemas across the UK on Monday, September 25th, presented with a recorded Q&A.