Aneesh Chaganty’s debut feature Searching in which a widowed father investigates his daughter’s disappearance, was released in cinemas two weeks ago, the latest film belonging to what producer Timur Bekmambetov has described as ‘screen life’, a genre or subgenre (or ‘language’ according to Bekmambetov) in which the story is told via computer screens, smartphones and webcams. Instant messages, internet surfing, Youtube videos, and social media often play vital roles in ‘screen life’ films, including the 2014 horror box office-hit Unfriended (directed by Levan Gabriadze and pictured above) and its 2018 sequel Unfriended 2: Dark Web (Stephen Susco).Both films were produced by Bekmambetov. Whereas the Unfriended films received mixed to negative reviews, critical responses to Searching have been largely positive. Nevertheless, Searching’s ‘screen life’ format and presentation, like that of the Unfriended films, has been referred to as a ‘gimmick’ by many critics and publications, in both negative reviews and positive reviews.

As something which is designed to attract publicity and attention, a ‘gimmick’ is something of a pejorative that dismisses the ‘screen life’ style of storytelling as having little intrinsic value. In the cases Searching and the Unfriended films, this is simply untrue. These ‘screen life’ films and their ‘language’ do have intrinsic value, the use of computer and smartphone screens complementing the subject matter and reflecting the very real notion that we now live much of our lives through these screens. Whether these films are good or bad is irrelevant to the value of their narrative techniques, and to dismiss these films as ‘gimmicky’ is to ignore a new, innovative way to tell stories and construct films.

.

Gimmicks from the past

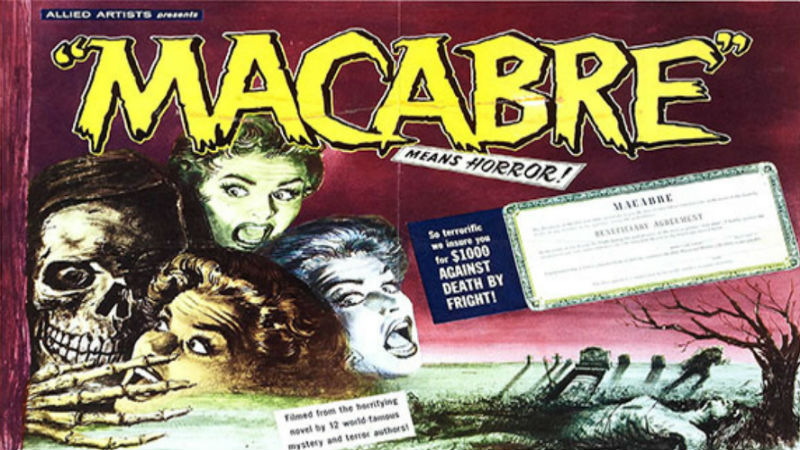

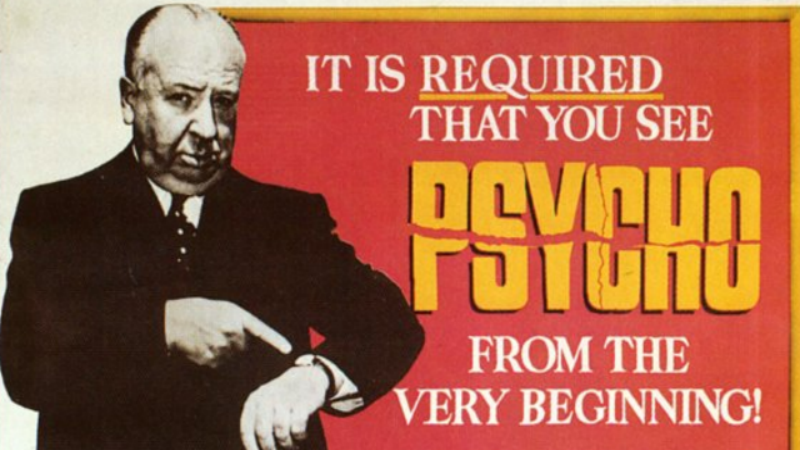

To be clear, the ‘gimmick’ of ‘screen life’ is not the same as other cinematic gimmicks. Cinematic ‘gimmicks’, it seems, can be split into two categories: on-screen and off-screen. Off-screen gimmicks, such as those in William Castle’s Macabre (1958, pictured above), House on Haunted Hill (1959), and The Tingler (1959) – respectively, life insurance for viewers should they die of fright when watching the film; plastic skeletons rigged to pulleys in theatres; and vibrating chairs that corresponded to the actions of the titular tingler (a parasite inside human beings that feeds on fear) – were gimmicks in the true sense of the word: marketing tools designed to attract attention and sell the film. Taking inspiration from Castle, Alfred Hitchcock employed a marketing gimmick in order to publicise Psycho (1960, pictured below), with audiences having to adhere to a ‘special policy’ preventing them from entering the theatre once the opening credits had finished. Needless to say, Hitchcock’s off-screen gimmick proved successful, generating plenty of hype and long lines of paying customers.

In comparison, the ‘gimmick’ of ‘screen life’ is not solely intended to sell the film. In Chaganty’s Searching, David Kim (John Cho) attempts to figure his missing daughter’s whereabouts by tracing her recent online activity. The use of computer screens, social media, and FaceTime calls makes narrative sense here, just as the use of social media and webcams makes narrative sense in Unfriended, in which a group of friends are terrorised by the spirit of their former friend, who committed suicide following an unflattering photograph of her going viral. Again, the ‘screen life’ style and structure is informed by the subject matter, and offers a degree of contemporary social commentary on how we live our lives. Evidently, the on-screen ‘gimmicks’ of Searching and Unfriended are not the same as the off-screen gimmicks of William Castle’s B-movies or Alfred Hitchcock’s marketing scheme for Psycho. In fact, when compared to these off-screen gimmicks, on-screen ‘gimmicks’ are not gimmicks at all.

Looking back, it’s not uncommon for innovative storytelling techniques to be disparaged as ‘gimmicks’. The found-footage subgenre – from which ‘screen life’ takes its cues – is frequently referred to as gimmicky, though interestingly the subgenre’s most famous example, The Blair Witch Project (Eduardo Sánchez/ Kevin Foxe, 1999; pictured below) – which implemented both an on-screen ‘gimmick’ in found-footage and off-screen gimmick in viral marketing -, was praised for its ‘mockumentary’ style upon release. The Paranormal Activity franchise, in contrast, has not fared quite so well.

Interestingly, a literary equivalent to found-footage exists in the epistolary novel, a novel written as a series of documents, such as diary entries, letters, or more recently emails. Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein and Bram Stoker’s Dracula serve as examples of ‘literary found-footage’, though whether anyone would dismiss these pieces of work as ‘gimmicks’ is unlikely. Coupled with ‘screen life’s ties to genre cinema, perhaps there is an element of snobbery and elitism to regarding ‘screen life’ as a ‘gimmick’, a piece of ‘low art’ – at best – that is unworthy of serious critical analysis.)

.

Another dimension

3D, repeatedly scorned as an overly-expensive money-making gimmick, was an essential part of the narrative in James Cameron’s Avatar (2009). The immersive 3D experience of the audience was intended to reflect that of Sam Worthington’s Jake Sully, as he embodies his Na’vi avatar and immerses himself in the culture of the Na’vi and their home world of Pandora. Just as Jake entered a new world when he is sealed within his link unit, the audience treated on a new cinematic world when donning their 3D glasses. Whether one enjoys the 3D experience is beside the point; the ‘gimmick’ has thematic relevance, Jake himself, like many film protagonists, acting as an avatar for the audience, our connection, our link, into the world of the film.

And in the same way, we are linked into Searching’s world through computer screens, Twitter trends, and viral videos. We see what David Kim sees. We are a voyeur, seeing into his life, viewing the world through his eyes. To an extent, we embody him, and the connection this creates with David allows for greater sympathy for his character and circumstance. There is far more to ‘screen life’ than ‘gimmick’ filmmaking. In the case of Searching, it is filmmaking at its most inventive, at its most thought-out, subject matter informing structure, art with purpose and meaning.

It may only be in its infancy, but the ‘gimmick’ of ‘screen life’ is likely here to stay. As it should be. As it deserves it.