An incredibly rare treat as part of the Picturing Austrian Cinema Symposium in Cambridge this past weekend: the appearance of double Palme D’or winner Michael Haneke for a post-screening Q&A alongside his most recent film, the divisive Happy End (2017). The crowd, eager for a glimpse of Austria’s most celebrated filmmaker, is abuzz. How will the man present himself? Will he be shy? Hostile? Bemused by his audience?

Confounding expectations, Haneke appears after the screening to be relaxed, casual even. Frederick Baker, Laura McMahon and J.D. Rhodes (University of Cambridge) provide a conversational atmosphere, while Dr Martin Brady (King’s College London) interprets for Haneke at an Olympian pace. Haneke complains of the cold as he removes his scarf, reclining into his chair to field audience questions, his face searching into the eyes of each questioner, while he jovially laughs off the more ridiculous assertions about his work. He isn’t afraid to give one word answers. He doesn’t want to talk too much about the political context of the film. But when someone grabs him, he’s off.

.

The beginning of the End

I first saw Happy End (pictured above) last Christmas day with my family, a domestic mistake that we have all agreed not to speak of again. I only bring that up in the interest of full disclosure. Watching it on a big screen, however, is an entirely different, undeniably better experience. Haneke teases his TV project ‘If it happens,’ (rumours are he asked for too high a budget), when asked about stretching out a narrative over 10 hours, he calls it ‘not difficult, for me it is a return. I made my first film at 47 and before then I worked in TV.’ But from the sheer level of detail that he packs into his frames, I hope that we don’t see Haneke leave the big screen entirely.

Happy End rankled critics. In his review last year, our editor Victor Fraga called it ‘a little trite if you are familiar with Haneke’s filmography and cinematic trademarks…too ambitious and not fresh enough.’ For sure, it isn’t as neat as some of his other works. Happy End isn’t an ‘anti-crowd pleaser’ like The Piano Teacher and Amour (2001 and 2012, both pictured below, respectively), which can be read fairly easily (while still being intensely detailed), but with some more distance between the hype machine and the film, its pleasures rise closer to the surface.

The sidelining of the refugee context, which sits in the background of every scene until it comes crashing in like a wave on the Calais coast has, in the last year, become more chilling, as the British media in particular seems to have entirely forgotten the crisis in favour of distraction by the Brexit games. For Haneke, who conceived of the film 2-3 years before he shot it, the film is ‘not about a specific nation. It could as well have been set in England or Germany. It is not about migration as much as ego-centrism.’

.

The man without a movie method

To a question that his films are full of scenes that are both seen and not seen, leaving out vital parts of the narrative, Haneke says that film is framed by the audience: this is usual for literature but not in film. When he writes he ‘describes the action itself, the exact object that will be depicted on camera, rather than ascribing any feeling or attempt at meaning to it.’ He says it is a question of how to show a feeling, rather than writing a script based on emotion. His next answer, about how he directs actors, also feeds into this Bressonian approach to filmmaking. Haneke calls acting reactive, about hard work, then pauses and says in English: “No method”. This is almost a sanding down of performance, which, in Happy End results in performances where the famous faces often do part of the work for us. The mere presence of Huppert brings a certain psychology to it, filling in the blanks that her few scenes hint toward.

His answer to a question about Facebook and social media is interesting. Is it all bad? “Idiotic. You cannot classify the medium itself as good or bad, only its use or misuse.” Haneke doesn’t use social media himself, but “you don’t need to have murdered someone to know how to depict it.” I wonder how this will impact his work going forward. Haneke’s famous use of the long shot, a surveillance camera aesthetic, is suited for the intrusive nature of social media. But Vine and Instagram promote shorter videos. Will his shot length begin to replicate this? Haneke repeatedly states that he ‘won’t skin the bear before he has shot it’ with regard to future projects, so only time will tell.

.

It’s alright, he moves in mysterious ways

Haneke also confirms a reading that his horizontal camera pans, from right to left, are an intentional device to unsettle an audience used to a left to right movement. After Haneke refuses to clarify his comments on #MeToo, another audience member questions the potentially eroticised gaze in Happy End toward Eve, the sociopathic 13 year old protagonist played by Fantine Harduin. “I didn’t see her myself as an erotic figure in any particular way. But the interesting thing about her story, the story of her poisoning her mother. I of course leave it open as to whether that’s accidental or deliberate, but what’s interesting about that storyline is its the only part that is not fictional, that is based on real events.

The continues: “Some years ago I read about this, it’s a real case that had taken place in Japan where a 14-year-old girl had begun poisoning her mother, and put the details of this activity onto the internet. Everything else in the film is more or less fictional, but this isn’t of course. And to that extent I also leave this open as to whether that is an accident. Or whether she is simply trying to calm her mother down who is being rather irritating, and has simply overdone it. Either way, it is not a particularly nice situation, but what it does deal with is the generation conflict and thus is also addressing questions of puberty. So sexuality certainly plays a part in that but I didn’t perceive her as being specifically an erotic figure. At least, its not intentional that way, but if you felt it, then that’s fine by me.’

By answering the question in this way, is Haneke suggesting that we read into the psycho-sexual aspects of the storyline here? For a filmmaker who is often reticent to comment on the meaning of his own work, this is a big clue. He responds to a question about whether there are bad readings of his work in kind: “there are none. The work exists for the audience. Only a professional audience [critics] get it wrong. Discussion with an audience is better than critics; newspapers only sell ideology.”

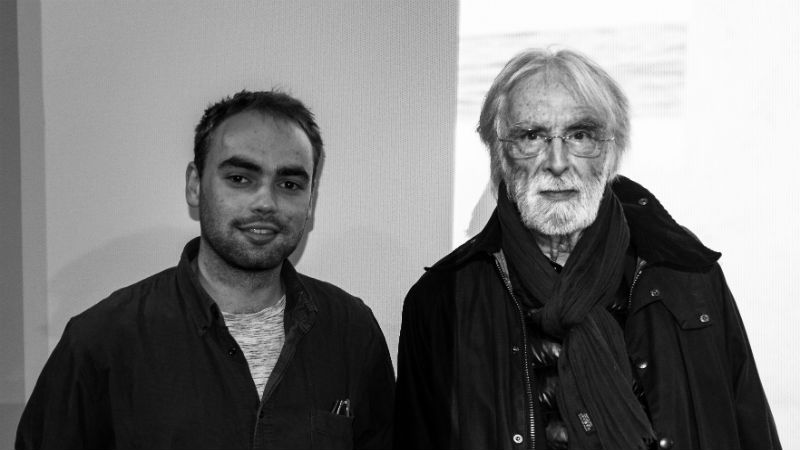

After the Q&A Haneke is happy to chat with audience members (those who can speak German or French, at least!) and pose for photos. Far from the image of the grump, Haneke (pictured above, alongside our writer Ben Flanagan) is a sweet, attentive man, whose presence offered us the opportunity to reassess one of his most undervalued films.