All humans begin as female. The Y chromosome – which is only present in males – is not activated in the first five to six weeks of embryonic development. This why all men have nipples. Beyond The Breasts is a bold documentary that investigates what it means being a woman in Brazil nowadays. Director Adriano Soares interviewed Brazilian women and some men of various races, creeds and sexualities, and the outcome is delightful, to say the least.

Brazil is teeming with contradictions, despite that clichéd view that it’s a liberal country. Women showing their breasts during Carnival is not necessarily an expression of freedom. In December 2015, a wave of sexism flooded the Brazilian Congress, as legislation making abortion illegal in all circumstances was proposed. Gynaecologist Jefferson Drezett, a vocal pro-choice campaigner and coordinator of a large and exemplary abortion clinic, stated: “Brazil abandons their women”. Beyond The Breasts also spoke to women at the Brazilian SlutWalk. The march was an intense revival of the feminists protests from the 1960s. Except that there were no more bras to be burnt; women protested topless.

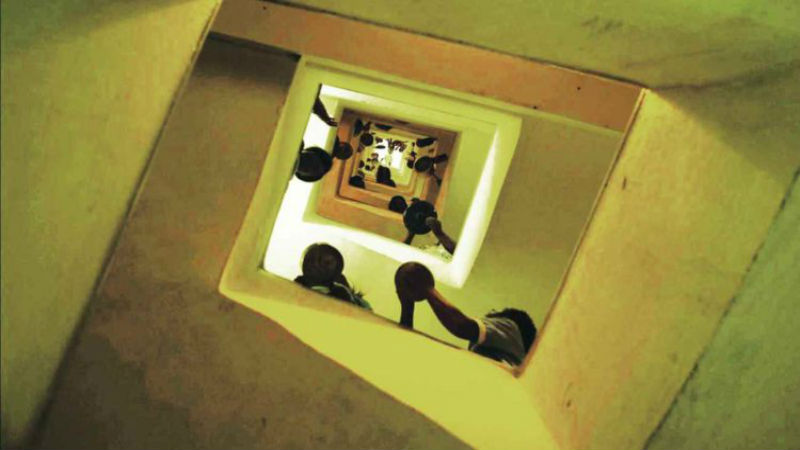

The documentary chose an artistic way to expose the deep societal wounds. The director is never didactic, taking a more fragmented approach. He suddenly interviews a blind man about gender and machismo. He reveals the astonishing reaction of a street artist who had a mastectomy. He frames bare breasts while his subject tells she was a victim of rape. He captures a lady talking the pleasures in masturbation. All the characters in Beyond The Breasts are very brave in their testimonies.

Identity is a key aspect in the film. Interviewees establish a bond with viewers while dissecting their own interpretation of self. A secret is not a secret until it is revealed. It’s the disclosure of intimacy that distinguishes each individual. Somehow Beyond The Breasts reminds us of what connects us. It is not the shape of our body. We are all mammals, both males and females have glandular tissue within the breasts. What is it then that makes us different?

DMovies, in a partnership with Infinita Productions held a screening of Beyond The Breasts in East London on October 26th, 2017. It’s available for digital streaming here.