Fellini’s eighth feature film has passed into the English language as a synonym for Italian exuberance, style and the ability to enjoy life without apology. No film has ever had such an ironic title as La Dolce Vita (“The Sweet Life”, had the film title ever been translated). In the film that made his international reputation, the Italian filmmaker pours cold water over the whole concept of a treacly existence. Instead, he reveals his home country as shallow, vacant and cruel. Indeed, he is not just depicting Italy but the whole era of the 1960s, which is the beginning of our own era, and all that he shows is still relevant and deeply prophetic.

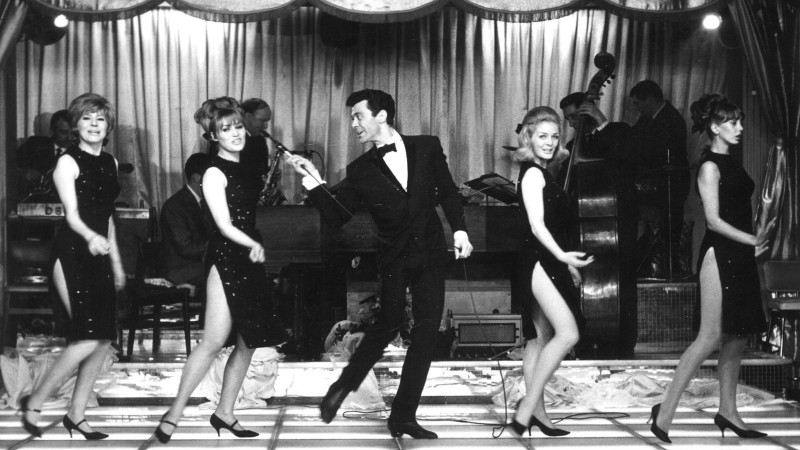

The ennui of is emphasised by the fact there is in this film there is no very obvious narrative. The story consists basically of a reporter named Marcello Rubini (Marcello Mastroianni) drifting through of the streets of Rome, and contending with a number of events. His girlfriend takes an overdose, he encounter an heiress, a movie star, and so on. Each scene is a series of episodes, in night clubs, at parties, in restaurants, etc.

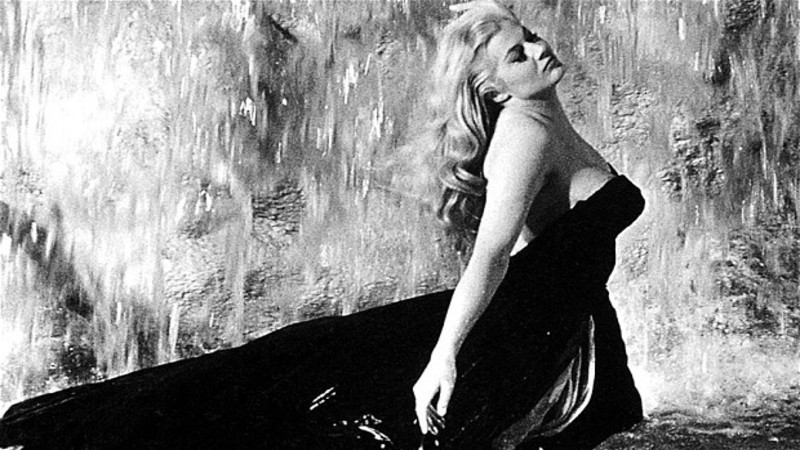

This is a movie built upon imagery and symbolism. The flying Christ scene mimics the idea of the Second Coming of Christ. Christ flies over his “eternal” city and what does he find? He finds paparazzi in the Via Veneto with rich, aimless people, he finds two children in a field pretending to have visions of the Virgin Mary, and a beautiful woman in a clinging dress climbing up the steps of the cupola of St. Peter’s, wearing what looks like a cardinal’s hat. The images of La Dolce Vita linger in the mind long after you have seen it.

The secular world he depicts is just as ridiculous and, perhaps, crueller. The one person who has any pretensions to intellectual insight is Steiner (Alain Cluny) and he shoots himself and his two children. The paparazzi wait until his wife gets off a bus and is told that her husband and children are dead and hope to photograph her reaction. The paparazzi are quite happy to run around a field in a downpour while two children pretend to have visions. It doesn’t matter to them. It’s all news. If it’s fake news, it doesn’t matter. It still sells. Even glamorous Rome is not that glamorous. The down at heel prostitute Maddalena (Anouk Aimée) whose flat Marcello Rubini stays at with a girlfriend lives in a depressing housing estate on the edge of Rome. You can’t get into her sitting room or bedroom except by walking over planks because the floor is flooded, and no one has come to do the repairs.

This film heralded the beginning of the 1960’s. Besides its teasing of Catholicism, it also featured openly gay characters. It was the beginning of the modern age which is still very much with us. It is a world of trivia, diversion and pointless celebrities. It believes nothing and knows nothing. The great fish that ends up on the beach right at the end of the film with its huge vacant eyes symbolises this. It could well be a metaphor for modern life, large, bloated and meaningless. The only aspect of today it lacks is poisonous politics.

The only people who seem to do an honest day’s work are the police and a beautiful young girl running a beachside restaurant and her busy, little brother laying out the plates on the tables. At the end of the film the girl tries desperately to communicate with Marcello, but she cannot be understood because the gap between her world and the world of the rich and spoilt people Marcello inhabits is too vast.

The film was loathed by many at its first screening in Milan. The Vatican hated the film and it was banned in several Catholic countries. Yet abroad it was immediately greeted as a masterpiece.

The 4k restoration of La Dolce Vitta was in cinemas across the UK on Friday, January 3rd. The BFI are holding a centennial celebration of Fellini’s work in 2020. On Mubi in June.