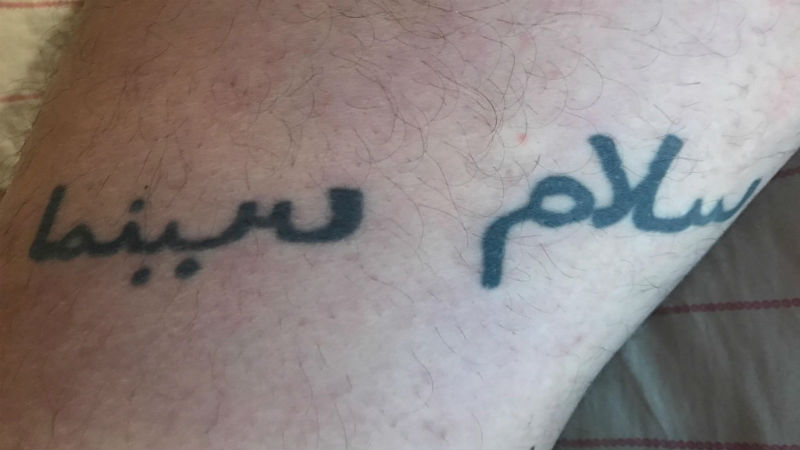

The occasion is the restoration of the poetic trilogy, which includes Gabbeh (1996), The Silence (1998) and The Gardener (2012). But to me, this moment wasn’t just about another commercial launch. It wasn’t about Mohsen Makhmalbaf, either. This interview was about myself. That’s because Mohsen Makhmalbaf is one of my biggest idols, and it was his 1995 film Hello Cinema that made me study cinema. So much so that I even tattooed the movie film title on my right thigh. They say you should never meet your idols. But somehow I doubted that I was in for a disappointment. Makhmalbaf has such a profound sensibility that I was convinced that we would get on just fine. I was right.

We met in one of those verdant and plush parks near his house in London. He has spent most of his time in the British capital since he defected from Iran in 2005, following the election of the ultra-conservative Mahmoud Ahmadinejad. He has directed more than 20 features (including 2001’s Kandahar, which made it to Time’s All-Time 100 movies) in the past 35 years, and he catapulted Iranian film to the forefront of world cinema. I felt privileged to talk to him in such a pleasant environment. After the interview, she invited me to his place, where we had coffee and scrumptious Persian pistachios. He showered me with DVDs, and shared intimate details of his career and personal life that surprised, shocked and – above everything else – moved me profoundly. But it wouldn’t be appropriate to publish those!

Below is our conversation in the park. We talked about the failure of capitalism, the role of the artist in the modern world, Trump, Iranian politics, Ken Loach, Joshua Oppenheimer and much more. Oh, and I did show him my tattoo (pictured at the bottom of this article). I was very hesitant because I knew Islam forbids tattoos. Read on and find out what Mohsen Makhmalbaf thought of the dirty scribble on my leg!

…

Victor Fraga – To me, your films are timeless. Still, could you please talk about the relevance of your poetic trilogy in 2018, almost 25 years after the first film (Gabbeh, pictured below) was completed?

Mohsen Makhmalbaf – Cinema is sound, image and concept. Gabbeh is about image. The Silence is about sound. And The Gardener is about concept. All three films have a sense of colour. Plus they are full of nature. They are a combination of colour, nature and poetry. As you pointed out yourself, they don’t relate to any specific time. You could watch them 20 years ago or in 20 years from now. There is no political and social issue attached.

If you look at the history of painting, from Van Gogh and Impressionism to Fauvism, that’s in these three films. What was Impressionism? The painter brought their frame from their room and put it outdoors, where they tried to capture nature. But nature was moving. The blue had a certain colour in the morning and another one in the afternoon. They wanted to capture reality, but reality was moving fast. So they got fast, too. It wasn’t real. It was a sort of magic realism. The three films in my trilogy have a sense of both reality and magic.

You should go and experience these films. Each person can create their own meaning.

VF – Were the three films initially intended as a trilogy?

MM – It took a long time to find a subject for the third one (The Gardener). First I made Gabbeh and then I made The Silence just two years later. They were like twins. But I always knew that they needed a third piece to complete them. That has happened with other films. For example, Hello Cinema and A Moment of Innocence (1996), they are like twins and I am still seeking a further piece to complete them as a trilogy. The President (2014), Marriage of the Blessed (1989) and Kandahar are a trilogy of political cinema.

I don’t have one style. I choose a style for each film, and sometimes for two or three films. It depends on the subject, and on my mood.

VF – Let’s go back in time. You became a filmmaker in 1983, shortly after the Revolution. Was making films under such strict censorship a handicap or was it liberating in any way?

MM – Censorship has always existed throughout the history of cinema. Even the first Iranian movie ever made 80 years ago was about censorship. It was called The Religious Man Becomes a Film Actor in English, or something like that. It was about a man who hated cinema, but then a filmmaker made a film about him so that he (the man) could see himself. In the end, the man became friends with cinema. We have cultural censorship because Iran is a very religious country. Painting, sculpture and music were forbidden because of religion. Censorship existed before the Revolution.

At least two good things came from the Revolution. Firstly, we stopped showing Hollywood films. Two years earlier, Hollywood cinema had killed the Iranian film industry. Secondly, people became more curious about reality. The New Wave of Iranian cinema created realism. Like holding a mirror to society. Television was full of lies, but cinema was honest. So people came to the theatre in order to watch honest films.

There was political, religious and cultural censorship. I made a film called Time of Love (1990) about a married woman who fell in love with another man. That was a huge taboo. But somehow we tricked the censors. For example, we gave them a specific script and we made a different film. We gave them a cut, and showed a different cut in cinemas. A few days later, they would remove the film. Same if we wanted to export a film. They put a stamp on something, and we would send out a different film. We had a lot of problems.

VF – How do feel about the episode where Asghar Fahradi refused to attend the Oscars in retaliation against Trump’s racist policies? Would you ever work or accept a prize in the US, under such horrific conditions?

MM – I don’t like Trump. To me, Trump is the worst person in the world. A dictator ruling a democratic country. You always get anxiety what will happen the next day. And I don’t like Hollywood cinema. For The Silence, we had two offers. One from Hollywood of U$4 million and another one for just U$200,000 from France. We took the low-budget option from Europe because we wanted to do the film our way. Hollywood insisted that we put a lot of music and big actors, and wanted to change the script, so I just said no. I just don’t like Hollywood. I don’t like Bollywood, either.

I don’t want to compare my work to Fahradi. We have very different styles.

VF – Many Iranian filmmakers including Jafar Panahi and yourself have been arrested. Do you think that you could return to Iran now and work there, since Ahmadinejad is no longer in power?

MM – It’s not about Ahmadinejad. The problem is our supreme leader, Ali Khamenei. Ahmadinejad was just his spokesperson. Like an assistant director of a dictator. People vote for the assistant. In this sense, Brazil is far better than Iran [alluding to the fact that I am Brazilian] because you vote for your president. We vote for the assistant. Khamenei is still alive and controls the country. Neither myself nor anyone in my family can go back to Iran. Worse still. They send out terrorists to kill me. They threw hand grenades when we were shooting in Northwest Afghanistan. Many people got injured. In Paris, I was under police protection because I was being chased by African terrorists. That’s why we moved to the UK.

Even Kiarostami couldn’t make his films in Iran, so the last two were in Italy and Japan instead. That’s why Iran is good and bad for cinema. There’s a sense of energy and reality in cinema. Everyone loves cinema. It’s like paradise to them. Comparable to Indians. On the other hand, censorship is bad.

VF – Do you anticipate that this could change. Earlier this week I watched Rudolf Nureyev’s latest biopic, who also defected (from the Soviet Union) and was persecuted abroad. But he did return bhome efore he died, and was briefly reunited with his mother. Do you think the same could happen to you?

MM – No, not at all. My mother dreamt of hugging me before her death. Sadly she passed away 40 days ago without doing it. That’s the disaster of living in exile. When our loves ones die, we are not near them. I don’t know whether they’ll ever let me back in Iran, or kill me. They are crazy, they are just way too scared of cinema. Because they think that cinema can create a movement against them.

VF – Let’s talk about a major loss we all experienced two years ago, when Kiarostami passed away. Could you please talk about your relationship to him?

MM – He was one of the greatest Iranian directors ever. We helped to create the New Wave. Kiarostami made Close-Up (1990), about a man who fell in love with cinema and with my name. Kiarostami went to his house claiming he was me. The purpose of the film was to show how much Iranian people love cinema. It was one of his best films. That’s when we worked together. His death was a tragedy. He went to hospital for a very simple reason and the surgery went wrong. He passed away for no reason. When I heard it, it was like a knife in my heart! It took me many days to get rid of this unbearable pain.

I heard that people were forbidden from gathering around his graveyard in Tehran one year after his death. They couldn’t attend the ceremony. The government are afraid that a public gathering could turn into another revolution.

VF – Let’s talk about the UK. Do you think that it’s becoming increasingly hostile to Arabs and Persians, like the US? Or is it better?

MM – Actually, I don’t have a home here. I’m my son’s guest. My daughter Samira also lives here. Our base is here, but we travel a lot. There’s nationalism, religion and corruption everywhere. It’s a new type of racism. Capitalism puts everyone in competition. We compete against each other for nothing. Everyone is a loser. Everyone feels that they failed. They get depressed. Even the supposed winners have anxiety that they could lose next time. This type of world is not healthy for our brains. We lose nature, we lose relationships, we become a part of the industry of capitalism. We become poorer. For example, in my childhood, just one diploma meant you were safe for life. Nowadays, even if you have three PhDs, you are not entirely safe. Your job is not safe. You are not safe in your border, because the next day you might be told to leave the country. Because the soul of capitalism has conquered this planet. We need Marx more than ever!

Google and Amazon have destroyed a lot of small businesses. The writer has no rights. The small shop in a village disappears, and people lose their job. In a way it’s good, because people serve each other. But it’s also bad, because people lose their jobs, their home. It’s a very crazy moment.

VF – Is there a relationship between this extreme capitalism and racism/xenophobia?

MM – I think that cinema is the art that could break the border. That could unite us though one single language. In a good way. I know you through Brazilian movies. You know me through Iranian cinema. And when we look at each other’s movies, we feel that we are the same. We fall in love in the same way. We get sad in the same way. On the other hand, in capitalism, there is no border. Capitalism unites us through nothing. We are customers. We have to pay tax for nothing.

Psychology is very important because we have become crazy! We don’t feel safe, we don’t trust each other, everyone is always trying to cheat. I don’t like this kind of life. We are not born to face such conditions. We are both to be healthy and happy. We are not born to compete and to achieve one million things.

Look at the UK, a lot of of people are living on the streets, and the NHS are failing many of us. I love the film I, Daniel Blake (Ken Loach, 2016; pictured below) because it’s the voice of British people. Cinema is the voice of the people who have no voice.

VF – Other than Ken Loach, which other filmmakers give voice to British people?

MM – I love Ken Loach and Joshua Oppenheimer. They are not about money, about profit. There’s a responsibility in being a filmmaker. It’s like being Che Guevara or Gandhi, but in an artistic way.

Last week an Iranian mother asked me for help because I know a little psychology. She said: “Mohsen, my son goes out on the streets every day so that he can have an accident and claim the insurance money for food. He has now lost a part of his body. Please talk to him. We need money for food, but I don’t want him hurt”. You see, cinema should be the voice of this kind of people! How can we remain silent when people are in prison, when half a million people die in Syria? The Iranian government, alongside with Russia, are responsible for this mess because they supported Assad.

VF – Can you please give us any clues about upcoming projects?

MM – When I look at the younger generation, I see that they have lost their hope for the future. They have lost their job and don’t trust the future. That’s why they move abroad. Also, we have a lot of sex nowadays, we are customers of each other, yet we have no real love. In my generation, when we fell in love with someone we trusted it was for life. Nowadays, people don’t trust each other. The children born under these conditions don’t have real families. Capitalism affects our morality. Each one of us, even the poorest people, have a strong sense of capitalism. Where do we go from here?

I think that this problem is not country-related. It’s universal. That’s why cinema is a messenger. Not from God. A messenger from the soul of humanity. It’s just like a horse that can sense an earthquake before it happens. The artist has an antenna, and he can feel that something is wrong. The artist is not a scientist, an analyst or a party activist. The artist has a certain sensibility, and can offer hope for the future.

VF – I have a very personal question and also a confession. When I watched Hello Cinema two decades ago, it changed my life. To me, your films epitomises the will to make cinema. And I wanted to make cinema. So I tattooed the film title on my right leg as a testament of my commitment to cinema (pictured below). Yet, I know that Islam forbids tattoos. Do you like my very personal tribute to your film, or do you feel offended?

MM – Oh my God, can I please see it [so I roll up my shorts]. Oh my God, can I please take a picture [proceeds to snap my leg with his phone]? A lot of things are forbidden under Islam. I’m not offended at all. I like it a lot. I’m shocked.

VF – When I made this tattoo I still dreamt of making cinema. And it’s only now that I’m directing my first movie, a documentary about media bia and the coup d’etat in Brazil two years. So both the tattoo and being here with you have a very special significance in my life.

MM – When did you get your tattoo done?

VF – I think it was 18 years ago, in the year 2000.

MM – Did you know that Joshua Oppenheimer also loved Hello Cinema? He told me in front of a large audience that it inspired The Act of Killing (2102).

VF – You inspired a lot of people, you see???

…

At this stage, Mohsen invited me back to his place (or rather, his son’s place, as he clarified earlier) and we talked for nearly two hours about the UK, Iran, Brazil, racism and shared our love for Tarkosvky. He specifically mentioned Mirror, and I explained to him that the 1975 film inspired me to create DMovies. The synergy was remarkable. As were his sensibility, his kindness, his generosity and sheer simplicity. This is an afternoon I will never forget!