At DMovies, we are proudly European. We believe in the values of internationalism, diversity and tolerance. We also believe that cinema should not be confined to the borders of one nation, and that we all benefit from the plurality of cultures, visions and perspectives. The characteristics commonly associated with Brexit – nationalism, intolerance, cultural and political arrogance – are an affront to the very essence of a dirty movie. A dirty movie is a movie that brings people together, that celebrates the universality of cinema in novel and thought-provoking ways.

None of our writers support Brexit. In fact, very few people in the film industry do, except perhaps for poor multimillionaire Michael Caine. Some of our recent interviewees have expressed their reservations about the Brexit, too. An elated Mike Newell told us a few months ago: “People like me are infuriated by Brexit. Brexit’s a very bad thing. Not just culturally, turning our backs on Beethoven, but where’s the money gonna come from?”. A more magnanimous Ken Loach stated, also in an exclusive interview a few months ago: “there’s a lot of fake patriotism, xenophobia, chauvinism. I think that cinema and the left in general should communicate that people are of equal value, whatever their origin, religion, the language they speak. Everyone is our neighbour. Our working class people have more in common with the working class of other European countries than with our ruling class.”

So we came up with a list of 10 dirty movies that investigate – at times directly and other times poetically and obliquely – the various phenomena that triggered Brexit, from overt and rabid racism to a general discontentment with the establishment and the feeling neglect in the more rural and impoverished parts of the country. We hope that these films will help viewers to reflect on the mistakes made, understand how unscrupulous politicians capitalised on these problems and sentiments, and restore our trust in a diverse, tolerant and inclusive Britain. We believe that the UK will eventually heal these wounds and rejoin the EU.

These films are listed in alphabetical order. Click on the film title in order to accede to each individual review.

…

.

Like a modern-day A Day in the Country (Jean Renoir, 1936), Bait observes the tension between rural and city folk and sees the darkness that misunderstanding can lead to. Edward Rowe’s increasingly desperate fisherman takes us along with him, as he lives hand to mouth and dreams of buying a boat to improve his catch. The tourists he was forced to sell his family home to, who repeatedly refer to themselves as a part of the community, keep trying to make his life even harder, though of course its all within their legal rights.

Bait is also great Brexit movie. But that’s not to say that it’s a single issue movie. This film will still be relevant long after we’ve got our blue passports, because these are battles that have always taken place, probably always will. But the way Jenkin relates past and present, generational and class divide, allows the film to take on mythic qualities.

.

2. Brexitannia (Timothy George Kelly, 2017):

The interviewees within this documentary are mostly in scrublands, council estates, broken down factories or a workingman’s club in areas such as the North-East of England, Northern Ireland, Clapton in Essex or the South West, describing their fears and what made them vote Brexit. The movie is was divided in two parts. We knew this was so because we were helpfully given the title “Part One: The People”, before the participants started talking. It was all vaguely interesting and amusing. The audience sometimes laughed out loud at some of the views held by this strange bunch, living somewhere outside the M25.

But there came a point when I was positively looking forward to what else we were going to get after ‘the people’, hoping that there would not be too much of it and that it was not going to go on for too long. Indeed, after “Part One: The People”, came “Part Two: The Experts. A group of half a dozen or so prominent individuals chosen to give their educated views on Brexit – one of them being Noam Chomsky.

.

3. The Brink (Alison Clayman, 2019):

Stephen Bannon is largely credited with the election of Donald Trump, which he describes as “a divine intervention”. Bannon remained his chief strategist until August 2017, when the two men fell out. It’s not entirely clear how close the two are right now. Nevertheless, Bannon remains very loyal to Trump’s cause and ideology. He works closely to the Republican Party. He was devastated when the GOP lost control of the House of Representatives, after the 2018 midterm elections.

The controversial political figure has made very good friends in Europe, with whom she shares many affinities. We see him meet up with Nigel Farage. They a passionate conversation about nationalism. Bannon believes that Trump’s election was a direct consequence of the Brexit referendum. “Victory begets victory”, he sums it up. We also watch him meet up with smaller and less significant leaders from the European far-right, including countries such as Belgium and Sweden.

.

4. Democracy (David Bernet, 2016):

This documentary does what the British media generally fails to do: it highlights the importance of personal privacy. In fact the UK seems to be moving precisely in the opposite direction. The highly controversial Investigatory Powers Act was passed last November with barely any objections from the political establishment, and very limited exposure in the media. The UK government now has unprecedented powers to snoop on our Internet history. While the film doesn’t highlight the UK context, if you are vaguely familiar with Tory privacy policy (or lack thereof) you might immediately realise the stark contrast.

It’s vital to note that, with Brexit, the UK may no longer be subjected to these laws, which could make the country extremely vulnerable to US corporate interests. Data privacy laws are very relaxed in the US, where an individual’s criminal and even health records are often publicly available or stored in databases with little to no protection.

.

5. Eaten by Lions (Jason Wingard, 2018):

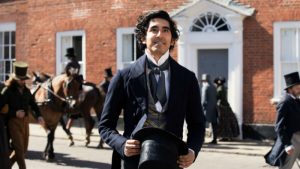

This is not a film that overtly deals with Brexit. The film delves into the topics of infidelity and paternal abandonment with the thickest tongue-in-cheek, darkly flippant and ironic tone. “She had those eyes, almost as if something was wrong with her” Irfan (Asim Chaudry) tells Omar (Antonio Aakeel) about meeting Omar’s mother. Aakeel and Chaudry are on fine form, but Jack Carroll, playing the disabled Pete, is the real scene-stealer. Simply watching him trying to act anything but impish in a seduction scene (across from the sultry Natalie Davies) shows a comedic talent that stands beside the decided discomfiture of Peter Sellers and Stan Laurel.

Kevin Eldon, Johnny Vegas and Hayley Tammaddon punch up the supporting cast with strong supporting performances, with the right hint of subtle xenophobia. Despite his background, Omar’s foster mother suggests that he belong with “his own” (pointing to his Indian father), a particularly potent and shocking moment and one that supports an exclusivist England that voted for Brexit and one that touches on an all too potent nerve.

.

2. Hurricane (David Blair, 2018):

It’s too easy to take most British WW2 movies (e.g. Dunkirk, Christopher Nolan, 2017) and claim they bolster the idea of Brexit – Britain alone against the world, defeating the dastardly Germans and so on. Hurricane is different. Its Royal Air Force (RAF) pilots are refugees from the Polish Air Force, wiped out by the Luftwaffe in a mere three days and kept on ice by Britain’s xenophobic War Office following their arrival in England. When they’re finally allowed into the air, these Poles turn out to be much better fighter pilots than the majority of Brits who are being slaughtered by the enemy at an alarming rate. Indeed, it’s the Polish pilots that turn the Battle of Britain around.

Hurricane is named after the RAF’s most widely used fighter aircraft and those portrayed here, at least when flying, are computer generated. Much of the CG work has been carried out in India (nothing wrong with that) on the cheap. The aircraft looks like computer models partly because no-one’s bothered to dirty them up and partly because there’s no attempt at reflecting the weather on their metal surfaces as real flying aircraft surfaces would do. Consequently, the flying sequences have an air of unreality about them which a little more budgetary spending in the right places could easily have fixed.

.

7. I Love my Mum (Alberto Sciamma, 2018):

This British comedy about haggling mother and son accidentally shipped to Morocco humanises refugees and also functions as a trope for Brexit.The essential misunderstanding between our heroes and their Spanish and French counterparts has overtones of Brexit negotiations, in which none of the countries can seemingly surmise what the other wants. While these later scenes meander at times, and rely on just a little too much flat sexual humour, they do get at the heart of why Britain and the rest of Europe seemingly can never properly get on.

Complemented by handsome photography of the Mediterranean Coastline and the Pyrenees, the rugged beauty of both Spain and France shows us what we are missing out!

.

8. Memento Amare (Lavinia Simina, 2017):

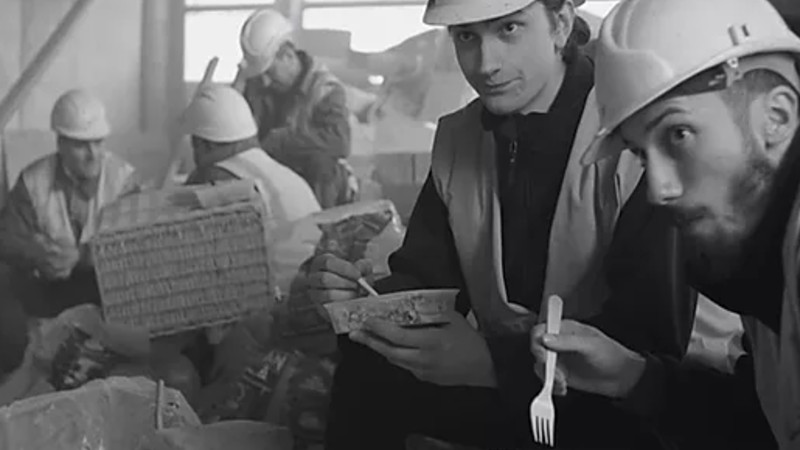

Mihai (Cristanel Hogas) is an immigrant. And as such he is divided between two nations. His beautiful wife and his young daughter dwell in Romania. Mihai is in London, where he toils as a construction worker, presumably in order to save money and provide a better future for his family. His relationship with his family is vibrant and colourful, while his life in the UK is sombre and colourless.

Because the movie is not entirely chronological, there are hints of the disclosure in the very opening sequence. The outcome looks bleak yet inevitable. And it raises a number of questions: Could the psychological wounds of Brexit could stay open for decades? How will the “orphaned” generations react to having their king (and their kingdom) taken away from them? Is it possible that the young may seek justice with their hands? Is warring the only road towards redemption? One thing looks certain: solidarity has collapsed (perhaps to the point of no return), and the future is not bright.

.

9. Postcards from the 48% (David Wilkinson, 2018):

It’s time to look back and evaluate what has been achieved since the referendum in 2016. Postcards from the 48%, as the title suggests, is a proud Remainer of a film. It lays out solid reasons as to why Brexit is insane, and the UK has been mis-sold a fantasy. It’s also a call to action: there’s still time to reverse a catastrophe. It’s mandatory viewing for those looking to consolidate their Remain views and opinions, and also for those in doubt.

A very pertinent analogy is made at the end of the movie. If you buy a house and find out it sits on a sinkhole, you should be able to to challenge your purchase. That’s why Britain should be given a second referendum and the opportunity to challenge the 2016 vote, which was heavily influenced by fallacies and lies.

.

10. The Street (Zed Nelson, 2019):

The devastating effects of gentrification are meticulously observed in documentary The Street, a scathing indictment of Tory austerity over the past four years. An empathetic portrait of a community in flux, it doubles up as a wide-spanning lament for a country that has seemingly lost its way.

As the double infliction of Brexit and Grenfell Tower impose even greater mental and physical harm upon the local population, the tragedy of Hoxton Street over the past four years becomes the tragedy of London, and by extension, the UK itself. Do the government care about working class people at all? Judging from this film, all evidence points to the contrary. While pointedly didactic (it may as well have said “Vote Labour” at the end) it earns the right to be, caring deeply for its subjects and begging for an empathetic solution.