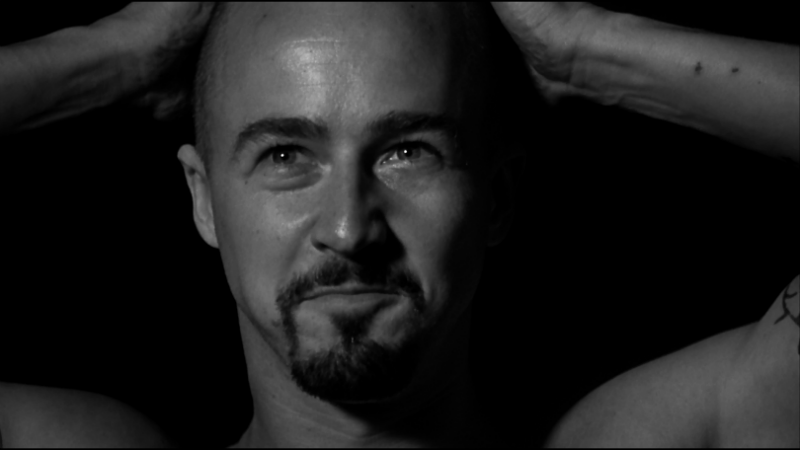

Everyone remembers the first time that their brains were forced to reconcile with that visceral and purposefully gruesome scene. Following an attempted car theft, the would-be assailant finds himself in dire circumstances, his front teeth clenched around the unforgiving edge of the curb. Forged by a maelstrom of unadulterated hatred, vitriolic rhetoric and an innate sense of injustice that he’d been wilfully seduced by in the face of a family tragedy, American History X’s (Tony Kaye, 1998) musclebound guide into the world of Neo-Nazism lifts his black combat boot and brings it crashing down upon the back of a young black man’s head with remorseless disdain.

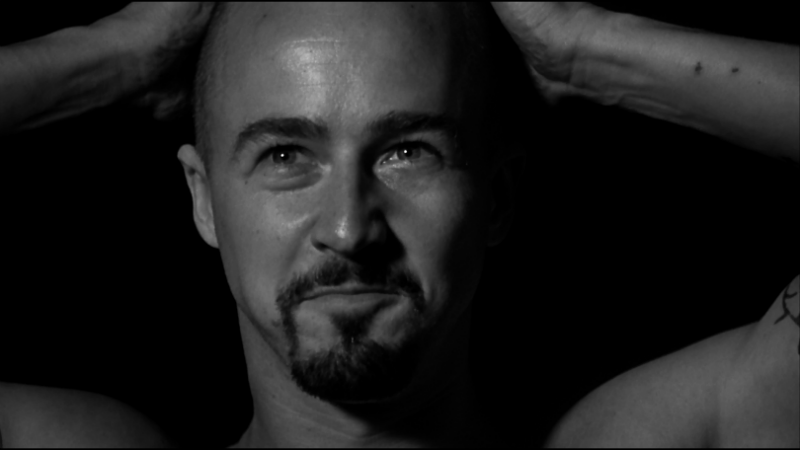

One life extinguished while another is irretrievably altered, the close-up on the shaven headed, swastika emblazoned Derek Vinyard’s self-satisfied grin and callous stare as the LAPD close in has became an enduring parable for the ramifications of allowing hatred to warp a malleable young mind.

Having attained cult status since its release 20 years ago today, American History X may have been widely disavowed by its notoriously idiosyncratic director Tony Kaye but the pertinence of its characters’ journeys has never waned in cultural significance. In fact, the undiminished relevancy of its portrayal of pervading racial tension, the perils of gun violence and the indoctrination of disenfranchised men into hate-fuelled subsects is not only a testament to the film’s timeless story and the performances of Edward Norton, Edward Furlong, Beverly D’Angelo and others but a scathing indictment of society’s reluctance to broach these issues in the two whole decades that have elapsed since it first hit the screens.

.

The collapse of the nuclear family

Orbiting around the ethnically diverse melting pot of Venice Beach, California, American History X may be a biting commentary on humanity’s misguided desire to impose barriers on our own kinship and compassion but is actually made all the more effective by being framed through the lens of a once harmonious turned highly dysfunctional brood.

The nuclear family personified, the Vinyards lived a comfortable life that contained all of the attributes of the ‘American Dream’ as viewed by an outside observer. Led by the patriarch Dennis Vinyard, the lives of his athletically and academically gifted eldest son Derek, wife Doris and kids Daniel, Davina and baby Ally all seem distinctly upper-middle-class. These characters can afford the luxury of discussing societal issues and the changing composition of the nation from the comfort of their dining room without having to worry about being unseated from their homely perch. Or at least that’s the case until the short-sighted vitriol that the father used to spew from the head of the table about “affirmative blacktion” and other such “bullshit” now has a warped affirmation for his kids due to his death at the hands of a drug dealer whilst on duty as an LA firefighter.

From there, all of the hardship and injustice that befell Derek Vinyard was inextricably linked to those convenient scapegoats that have been cited by the disenfranchised or aggrieved since time immemorial – those that are different from us. In the weeks and months that follow, the seeds of hate that were haphazardly planted on that day lead to Derek’s indoctrination into neo-Nazism by the parasitic Cameron Alexander (loathsomely realised by Stacy Keach) and his de-facto leadership of the “white power” gang the DOC that would eventually lead to his incarceration little more than 12 months down the line.

.

History repeating

In one particularly galling scene that is taken from his tenure as the group’s organisational spearhead, we see Edward Norton’s Derek rally his troops with an impassioned speech about the plague of “border jumpers” that were “bedding down in their state” and wreaking havoc on the nation whilst they are, allegedly, “losing.” Preached to the converted assembly just minutes before they’d go on to raid a local supermarket owned by a Korean man and largely staffed by Mexican immigrants, the mobilising capabilities of this skewed ideology crestfallenly hits home when viewed in the paradigm of today’s US.

Just days ago, a right wing extremist that saw his nation as being defiled by the Jewish community took to a Pittsburgh synagogue with an assault rifle, killing eleven in total. “I can’t sit by and watch my people get slaughtered”, proclaimed Robert Bowers on the far-right social media site Gab just hours before the attack, “screw your optics, I’m going in.” Teamed with the horrific prejudice that was on display at last year’s Unite The Right’Rally in Charlottesville, it is hard to believe that verbal incitements such as Vinyard’s could retain every bit as much destructive power as they did 20 years ago. Until you remember that in this dystopian fever dream, they are actually vindicated by a president who actively refused to condemn neo-Fascists at the Virginia event and has unrepentantly dehumanised Mexicans and immigrants from other ‘shithole’ countries on numerous occasions.

Flash forward to three years on from the height of Derek running roughshod over Venice, he re-emerges as a vastly different man than the embittered young insurgent that was given the lesser conviction of voluntary manslaughter due to his brother Danny’s reluctance to testify. The recipient of a philosophical rebirth after he was not only forsaken by his white ‘brothers’ that aligned under their vacuous credo but saved from certain death by his black co-worker Lamont, his appearance and mindset may have been irrevocably changed during his time in the Chino correctional facility but the groundwork he’d laid on the outside world has been expanded upon at an unforeseen rate.

Rather than viewing his brother’s plight as a cautionary tale, Furlong’s Danny Vinyard has faithfully retraced his steps and is now a prized protégé of the same organisation which its former leader wishes to renounce. Upon re-entering society, Derek is immediately forced to rationalise with both the tangible and more deep-seated ramifications of his actions on his family. Rather than the picket-fenced splendour of suburbia where he perpetrated his most heinous act, his mother and the kids have been forced to downsize to a tiny apartment which is more akin to the conditions in which the disadvantaged minorities that he’d once seen as a societal scourge subsist in.

.

Is there a way out?

Hoping to disassociate himself from the vile hate speech which he used to espouse, Derek ventures to the very party which heralds their prodigal son’s return in order to tell Cameron and his bumbling yet dangerous comrade Seth that both he and Danny will be taking no part in it from here on out. In a chilling riposte that seems sickeningly prophetic when viewed in a modern context, Alexander attempts to reason with the reformed skinhead by stating “wait until you see what we’ve done with the internet.”

As much as he attempts to show the world his propensity to change, Derek can’t outrun the chain of events which he set in place all those years ago. From the moment that he began to proliferate on the benefits of a racially pure nation, he’s been set on a collision course with tragedy that concludes like all too many do- in a hail of gunfire. In an unsavoury American tradition that dates back to the 19th Century, the propagandistic hubris of Danny would exact a heavy toll as he was gunned down in cold blood by another student due to his overt disdain for his gang-affiliated black classmates.

As he cradles his brother’s bullet-ravaged and bloodied body, an inconsolable Derek sees the entire tale displayed before him as he babblingly yelps “what did I do? What did I do?” Harrowing as it may be, this introspective enquiry bittersweetly correlates with the words of Avery Brooks’ Dr Bob Sweeney who’d posed a simple yet cutting question to the imprisoned Derek: “Has anything you’ve done made your life any better?

Far from solely serving as an unflinching look at the US’s systemic issues or the ruinous nature of hate and discrimination, this is one of a myriad of examples in which both writer David McKenna and Tony Kaye must be praised for the sheer efficacy of the approach they took to bring the film to fruition. A stylistic yet impactful choice, the juxtaposition of each of the film’s explorations of the past being rendered in monochrome whilst the present is seen in technicolour beautifully symbolises the transformation of Derek’s mind from neo-Nazism to a inclusivity-based stance. In the past, Derek’s life was rendered solely in black and white, with his worldview set in stone and governed by a series of puritanical absolutes. Yet once he’s underwent his deprogramming, Derek can now see all of the shades of grey that make societal issues less cut and dry whilst also regaining the ability to see the beauty in the world that had once been obscured by his father’s untimely death.

.

A film in the woodpile

Alongside this visual metaphor, what separates American History X from other films that portray members of hate groups is the naturalistic approach it takes to the central characters’ development. As we follow Danny Vinyard over what turns out to be the final 24 hours of his life, we see a young man that is not simply a vessel for a corruptive outlook but a multi-layered individual that’s capable of the full spectrum of emotions. Mere hours after we see him appeasing the deplorable Seth with talk of his hatred for anyone that isn’t white protestant due to them being a “burden to the advancement of the white race”, we then watch on as he picks up his infant sister and lovingly gives her an ‘airplane ride’ before pleading with his ailing mother to quit smoking for the benefit of her health.

In this instance; alongside the aftermath of the infamous dinner scene in which Derek displays his slew of Nazism-inspired tattoos to dissuade Dr Murray (Elliot Gould) from pursuing a romantic relationship with his mother, the viewer is given a glimpse of the redeemable humanity, love and empathy that ill-fittingly resides within these men that strive to maintain an outward appearance of cold-blooded monstrousness. Aligned with its heartrending conclusion that abstains from giving us the sort of redemptive narrative that is so beloved by celluloid in favour of a realistic depiction of a man reaping what he’s sown, it shows that the greatness of American History X doesn’t spring entirely from its continued applicability as a look at society’s flaws but the fact that it remains a stellar work of cinema even if viewed in isolation from all of its pervading relevancy.

Just as Danny heeds Derek’s wisdom to “go out on strong” on the quote of another, there’s no way to better encapsulate what makes this film so enduringly horrifying and brilliant all at once than to conclude with this profound remark that comes to the surface in the wake of his death: “Hate is baggage. Life’s too short to be pissed off all the time. It’s just not worth it.”