[dropcap]D[/dropcap]o you know what it feels like to be an Aboriginal drag queen? Well, you are about to find out. In the documentary Black Divaz, which opens the upcoming Native Spirit Film Festival (taking place between October 11th and 21st), six fantastic Aboriginal drag queens compete for the title of Miss First Nation pageant in Australia. The new queens of the desert are called Nova Gina, Isla Fuk Yah, Crystal Love, Josie Baker, Jojo and Shaniqua.

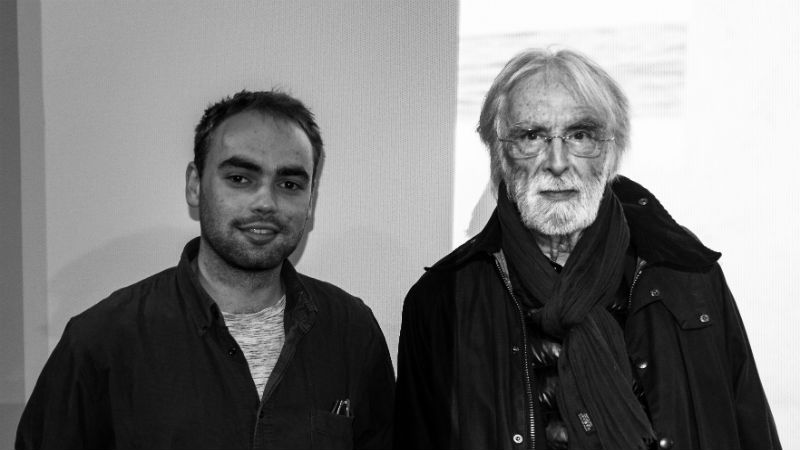

We have taken the opportunity to chat to the film director Adrian Russell Wills, an LGBTI Aboriginal man himself. He talks about the prejudice that Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islanders people face (sadly, he argues that it’s increasing), challenging taboos, how cinema has helped to voice and to liberate a marginalised community, and why every single one of us should live out our lives at full throttle and full volume!

Don’t forget to click here and get your ticket right now!

…

Victor Fraga – How was Black Divaz born? Where did the idea/impetus come from?

Adrian Wills Russell – Black Divaz was born from an initial call out on Facebook for expressions of interest to compete in the inaugural Miss First Nations Competition being held in Darwin in September 2017. Created by Queens The Ultimate Drag Crown, this event was the brainchild of Miss Ellaneous, aka Ben Graetz, and business partners Marzi Panne and Adriana Andrews. My understanding was that the impetus came from the “want” and the “need” for First Nations Drag queens to be seen and honoured in the same way mainstream drag culture is here in Australia and around the world. With the film Priscilla – The Queen of the Desert drag (Stephan Elliot, 1994) culture from down under had played a major role in the art from of drag becoming part of popular culture, this and then years later the onset of the television show Ru Paul’s Drag Race and Ru Paul’s career, people were starting to realise how drag queens reflected all of us, the way we want to see ourselves and the way we astre never brave enough to project outwardly for the rest of the world to receive.

Personally, I have also felt over my years on the gay scene that in Australia we still had a big problem with racism in the LGBTQI community and the fact that Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islanders were seen as good for business (for bars, clubs and pubs) but behind our back we were ridiculed and ostrisised, often being made fun of by other non-indigenous drag artists. That is why for me Black Divaz was an opportunity I could not and would not pass up. Also, in Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander communities there was and still can be a huge issue around homophobia, and transphobia. The suicide rate for Indigenous Australians are among the highest in the world, and in fact for some age groups it’s the highest. Now, how many of those statistics represent or are connected to homophobia / transphobia is difficult to say, but I feel like it is much higher than we even think. We needed to have the conversation in our communities, and in our families and a film like Black Divaz, hopefully can break down some of the barriers for that conversation and understanding to take place.

VF – Please tell us a bit more about the research with the Aboriginal communities, and how did you engage with them?

This was about a competition, and a group of drag artists / queens. I am also a gay Aboriginal man who has lived within and around the drag / trans community for many years. I felt like I knew and understood this film having researched it through my experiences, a lived experience. As with all our filmmaking, we sought permissions to film on the country in which we were filming, from speaking with the local Aboriginal land council, and the elders within those communities. But also, it’s important to state that the queens themselves spoke for their communities, and families by engaging in the competition and the film. Every single one of us, be it filmmakers or participants were making the film and competing for the same reasons, for the same goal. To bring more awareness and understanding and to celebrate and honour First Nations LGBTQI people, and the incredible struggle they endure in order to live their authentic selves, and their truth. And in this I refer to past, present and future generations of First Nation LGBTQI people.

VF – What was the most satisfying part of this cinematic journey for you as an artist?

ARW – The most satisfying part of the cinematic journey for me was the moment I took my seat at the Premiere Screening in Sydney, as part of the Sydney Queer Film Festival. Ask anyone who was in that room that night, there was something else happening in that cinema. It was like every single person in there had been destined to be there in that moment, to give the queens their love, their hearts and their endurance. The energy was unlike any other screening I have been a part of, and there were filmmakers in the room whose films have screened at the most prestigious festivals in the world and they too made particular mention of the audience and the screening.

Every single one of us was overwhelmed, so much so I still am processing the love in that room that night. We received two standing ovations, and for me as a gay Aboriginal man, I couldn’t have been prouder of the queens in our film. Their courage and rawness was a gift that had taken a lot from each of them to be in that place to give in and of that moment. And their gift will hopefully be a light in the dark for generations to come after we are long gone. But also, hopefully things change for the better and as they should.

VF – Did you encounter any resistance from the more conservative members of the Aboriginal and Torres Strait islanders community?

ARW – I didn’t encounter any resistance from anyone about our film, in fact quite the contrary. If there was any I didn’t hear it, and to be honest anything negative that people may have had to say was drowned out by the noise of thank you and appreciation for the queens courage in telling and sharing themselves in the film. if anything there was a sense of “about time”.

VF – What was the most challenging part of the experience?

ARW – The most challenging part of the experience, and in any filmmaking experience is what you learn about yourself. Particularly I find as a director. Being in the director’s seat, in my experience, illuminates all your strengths and weaknesses at once. What you are most best at is just as visible as your weakest parts. For some reason it takes the best of you and the worst of you to do this job. It’s something that I hope to get better at, or at least manage better but it’s also something that (I believe) is part of being an artist and pursuing something so unique in vision and in form. The artists that I admire in the world, and who have passed I feel this is obvious in their process as well.

VF – Aboriginal people still suffer from discrimination. Is crossdressing a tool for liberation and social integration?

ARW – I don’t really subscribe to the crossdressing part of this question, because for me that is too limiting and potentially diminishes what is happening within the art of drag. Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islanders continue to suffer discrimination at an unacceptable level, and if anything it seems only to be getting worse. Whilst roads have been built between black and white in this country, the patronising manner in which First Nations people’s lives are managed and politicised is very concerning, and I don’t know if I can see a resolution coming in the near future.

These girls in our film highlight what courage looks like, and how it’s vital you don’t wait for an invitation to your life, you get out there and live it at full volume. You can see the vulnerability and self evaluation that is going on with the characters in the film, but what comes through strongest is endurance, resilience, and courage. The best social integration aspect to this film is it’s existence, and is it’s message. Fuck being asked to sit at the table, sit the fuck down and start the conversation! For me this film is a story about my hero’s, and that liberates me, my friends, my family and hopefully my community. Great question.

VF – What are you working on next?

ARW – I am very excited to be working on the screenplay for my feature debut (drama), which has been a long time coming, as it should. Again, it’s a story about another hero of mine. I don’t know what it is, but being Indigenous and Queer is like having a super power, and with that power comes this vision, and I can’t wait to share that vision with the world.

…

Eoghan Lyng contributed to this interview.