It’s 2018, and neoliberalism is steadily morphing into neofacism. The UK is sleepwalking into a totalitarian regime. Extreme surveillance has already been introduced in the shape of apparently harmless RFID tags, and 75% of population already use them. People have become another trackable item in a gigantic Internet of Things. And that’s not all.

Eloise (Shona McWilliams) is a documentary filmmaker who suspects that she is somehow being brainwashed or manipulated by the UK government. Tacit questions are soon raised: is the RFID tag far more powerful and sinister than a simple trackable device? How is Eloise being controlled? How vulnerable is her body? Or are these fears just the byproduct of a highly susceptible mind and a feeble soul? Where do you draw the line between imagination and paranoia?

The topic of Draconian vigilance and the erosion of civil liberties is extremely pertinent right now, and Andrew Tiernan’s film could be frighteningly prescient. The highly controversial Investigatory Powers Act was passed last November with barely any objections from the political establishment, and very limited exposure in the media. The UK government now has unprecedented powers to snoop on our Internet history. Edward Snowden tweeted: “The UK has just legalised the most extreme surveillance in the history of western democracy. It goes further than many autocracies”. We are quickly turning into an Orwellian society.

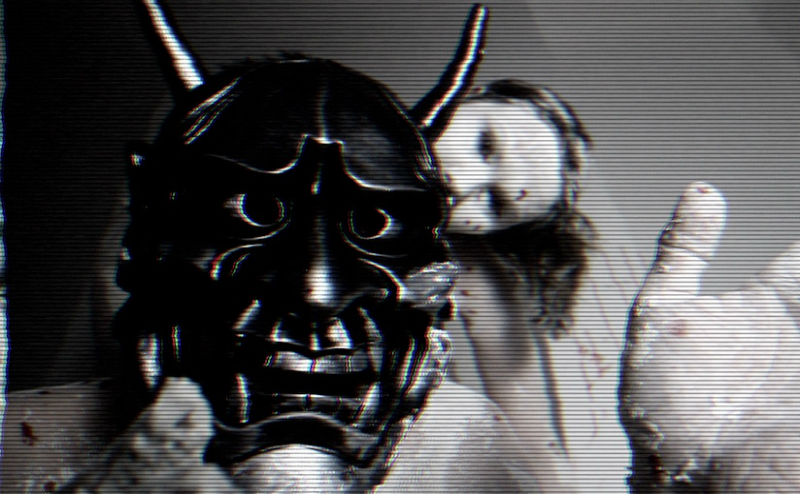

This British sci-fi flick is urgent in its currentness and simplicity, without ever resorting to didacticism. The narrative is multilayered and inventive, and it isn’t always possible to distinguish between reality, imagination, allegory and a fourth novel layer: a government devised-reality within the character’s brain. The images in the movie range from very fuzzy and grainy to very sharp and crystal clear, with the occasional TV footage thrown in. This complex visual mosaic suggests that the line between reality and imagination is very thin and volatile, and it’s very easy to meander from one realm to the next. Nothing is quite what it seems. The imagery is often scrambled, and the plot in non-linear – just like our brains.

One element that is constant throughout the movie is the somber tone, sometimes supported by a cacophony of strange sounds: a harmonica, scratchy strings, white noise and a music score by the Hackney Massive. The result is an eerie world, populated by nervous and despondent human beings. The only hope are the young people willing to stand up and fight.

UK18 is dotted with deft comments on how the increasingly autocratic UK government is failing its population. There’s ethnic profiling: the film notes that black people are typically the first victims of stop and search and other invasive practices already widespread in the UK. Ethnic profiling is merely an euphemism for intitutionalised bigotry. Perhaps more significantly, the film highlights the stigmatisation of independent thinking: anyone who questions the law is promptly denounced as a “terrorist” or a “conspiracy theorist”. Masses are to remain apathic, or “dumbed down”. Defectors are killed and their murders are conveniently dismissed as an “unfortunate operational necessity”.

Alongside with our personal freedoms, our values of diversity and tolerance are quickly dissipating. Extreme surveillance represents the sheer failure of capitalism. UK18 is a powerful statement against the dictatorial nature of the Orwellian state, and the catastrophic consequences for each one of us, whether you support the system or not. It is also an alarm call: the bomb of totalitarianism is ticking very fast, and there may not be enough time to run unless people take action right now.

Ultimately, UK18 is a nightmare vision of our very near future: a dystopian society, where the only hope lies in the hands and the voices of the few people willing to face up the establishment. So stand up and fight!

Actors in the film also include: Ian Hart, Jean-Marc Barr and Jason Williamson.

DMovies screened UK18 at the Regent Street Cinema in April 2017. Click here in order to view the film online.

Don’t forget to read our exclusive interview with Andrew Tiernan by clicking here, and to watch the movie trailer below: