Forget City of God (Fernando Meirelles, 2002), Traffic (Steven Soderbergh, 2000) and Christiane F. (Uli Edel, 1981) – Ma’ Rosa isn’t just another movie about drugs. It is an urgent and minute register of the several layers of Filipino society, with ingredients such as family devotion, drug trafficking, prostitution, homosexuality, police corruption and much more.

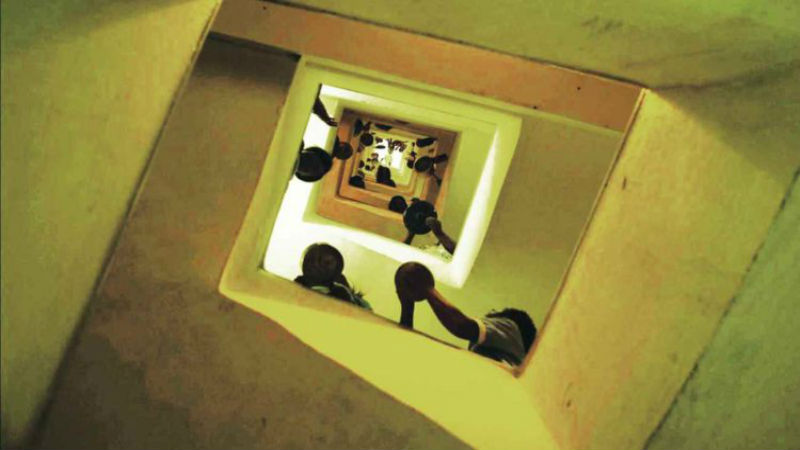

Cinematographer Odyssey Flores takes you into a wild and frenetic trip through the streets of Manila, where Ma’ Rosa (Jaclyn Jose) has set up her small drug business. She is at the bottom of the chain of the drug business in town, but most of all she represents the strength of a matriarchal society. Nothing is glamorous in this picture. What cameras show are the real colours of a very subversive life choice. The raw cinema vérité feel will blow you away.

Ma’ Rosa lives in a shanty town and sells crystal meth – nicknamed ice – to locals. The drug is highly addictive and users feel agitated, paranoid, confused, aggressive and sometimes even psychotic. All her family is involved with the business, including her husband and her three kids. One day, she is tipped off by a neighbour and arrested along with her husband by the police. The offence is non-bailable, due to the high quantity of drug under her possession. They do not charge the couple; instead they try to torture and extort money and information from them. Ma’ soon grasses on other dealers, but the police dismisses them as minnows. They want to catch the big fish.

The only solution to free Ma’ Rosa and her husband is if her kids raise the money police wants. Then, the real trip into the Filipino society turns edgy. The children will resort to some very unorthodox measures in order to free their parents.

Jaclyn Jose’s portrayal of Ma’ Rosa won her Best Actress prize in Cannes. She is capable of communicating deep emotional states with very few words. Her acting is a constrictive and yet very energetic, just like small fish caught up in a large net. The acting is supporting by a very harrowing soundtrack. Films like Ma’ Rosa are a cold look into an topic our eyes tend to neglect. Ma’ Rosa’s predicament is part of a game that perpetuates poverty in countries like the Philippines. Drugs and corruption are part of this game, and as we see in the end of the movie, it is impossible to break away from the cycle.

Ma’ Rosa is showing as part of the 60th BFI London Film Festival starting next week – just click here for more information.

Watch the film trailer here:

.